Stan Winston Studio developed new GODZILLA creature designs while Sony Pictures Imageworks began preliminary work on the film`s digital FX. © 1993-1995 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd. © Stan Winston Studio © 1994 Sony Pictures Imageworks

Stan Winston Studio developed new GODZILLA creature designs while Sony Pictures Imageworks began preliminary work on the film`s digital FX. © 1993-1995 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd. © Stan Winston Studio © 1994 Sony Pictures ImageworksCreature Concepts, Previz, Set Designs and More Are Created Before Sony Pulls the Plug

Author: Keith Aiken

Special Thanks to: Please See ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS in Part 1

A SCIFI JAPAN EXCLUSIVE

- FACE TO FACE WITH THE MISSING LINKS

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- ORIGINS

- DEVELOPING THE STORY

- THE SCREENPLAY

- DIRECTOR HUNT

- THE FIRST FX TEST

- JAN De BONT

- PRE-PRODUCTION BEGINS

- CONCEPTUAL DESIGN, ROUND ONE: GOJIRA PRODUCTIONS and STAN WINSTON

- STORYBOARDS

Part 3

- DIGITAL EFFECTS

- CONCEPTUAL DESIGN, ROUND TWO: WINSTON STUDIO

- FINAL PREPARATIONS: CASTING plus MINIATURE and PRACTICAL EFFECTS

- THINGS FALL APART

- RETRENCHMENT

- THE REWRITE

- THE DISCONNECT

- REACTION

- AFTERMATH

- GODZILLA (1994) CREDITS

DIGITAL EFFECTS

“They were looking for an effects facility. It was just a huge job." --Digital Domain co-founder James Cameron

"GODZILLA was threatening to gobble up every effects house on the planet." --unnamed FX technician

"The studio thinking is `What if you could do JURASSIC PARK with a highly recognized "name" monster?`," said Terry Rossio. "You could have those incredible effects where you actually believe this thing was actually stomping through a city and combine it with the worldwide name recognition of Godzilla. They`re looking at state-of-the-art effects, digital effects, and have that be part of the draw... part of what distinguishes this movie from all the other Godzilla films."1

"There was a great sequence where Godzilla wipes out the Pacific naval fleet in San Francisco Bay," recalled Ricardo Delgado. "Looking at the storyboards I was thinking, `How are they going to do this?` because it was the most ambitious effects sequence I had ever seen."2

Jan De Bont wanted to create three-dimensional CGI sets for GODZILLA. This technique would later be used to recreate 1933 New York City in Peter Jackson`s KING KONG remake. © 2005 Universal Studios

Jan De Bont wanted to create three-dimensional CGI sets for GODZILLA. This technique would later be used to recreate 1933 New York City in Peter Jackson`s KING KONG remake. © 2005 Universal StudiosTo accomplish that goal, GODZILLA would need to push the envelope of visual effects techniques. JURASSIC PARK had clearly raised the bar for FX but the film`s dinosaurs were shown for less than fifteen minutes, with approximately four minutes of that time devoted to CGI. Barely a year later, Jan De Bont and Boyd Shermis intended to have computer-generated versions of Godzilla and the other creatures featured onscreen and in action for much of their film. "This is the first film of this magnitude where the lead character, who spends a good deal of time onscreen, is virtually 100% computer animated," Robert Fried declared.

De Bont intended to take full advantage of the advances in digital technology, promising that GODZILLA would have, “a lot of things that haven’t been done before, totally new effects, more complex than JURASSIC PARK.”3

Among those advances would be the creation of photo-realistic virtual sets for the monsters to “perform” on. Computer generated environments have become a standard feature in modern effects films, but the technique was not yet in practice at the time GODZILLA was being developed. "Jan wanted to use all three-dimensional CGI," Ted Elliott recounted that. "That means you create a full environment and move the creatures through it, as opposed to two-dimensional where you move the monsters across a photographic plate. Jan insisted that he wanted to create the whole environment."4

After breaking down the visual effects sequences in the screenplay, Boyd Shermis estimated that GODZILLA would need more than 500 computer-generated effects... triple the amount for any film to that date. When asked if there was any apprehension among the crew about being able to match De Bont`s vision with 1994 digital technology, Shermis replied with a simple "Yes." But he quickly added that, "Most of the technology existed, but it was very cutting edge at that time. We would have needed to do some serious R&D [research and development] for things like the water, fire simulation, etc." Concerned over these technical issues, TriStar executives decided to push back the start of production on GODZILLA until early 1995.5

De Bont and Shermis initially approached ILM (Industrial Light and Magic) -- the Academy Award-winning visual effects division of Lucasfilm that had created the amazing CG dinosaurs for JURASSIC PARK -- to produce the digital effects for GODZILLA. As the top FX studio in the world, ILM was well-equipped to handle all of the myriad of digital effects planned for the film. But they had a packed workload and turned down the offer, citing that GODZILLA would require far more computer graphics than any one company could handle.

Looking elsewhere, Boyd Shermis and other members of the GODZILLA crew were particularly impressed by the visual effects in a new Rolling Stones music video which had debuted that past July. Directed by David Fincher (SE7EN, FIGHT CLUB), the video for "Love is Strong" featured members of the band and several models, digitally enlarged to Godzilla`s size, wandering about New York City. Ricardo Delgado recalled that, "There was a Rolling Stones video where they’re running around New York that Jan and the visual effects crew pointed to and said, ‘That’s what we’re going to do’. I remember that vividly. Everyone from Jan to Joe to the visual effects people saying ‘We’re going to have Godzilla running around just like that. It’s going to look real."

The visuals for "Love is Strong" had been created by Digital Domain, the digital effects house established in 1993 by James Cameron, Stan Winston and Scott Ross, the former Senior Vice President of LucasArts Entertainment Company. Ross had spent several years working for George Lucas, but had grown frustrated that his boss was focusing on theme parks, video games and real estate after the failures of HOWARD THE DUCK (1986) and WILLOW (1988). "I left because I wanted to make movies," he acknowledged.6

Stan Winston had his own explanation for launching the new company, stating, "There`s a reason why I now own Digital Domain with Jim Cameron and Scott Ross, the second largest computer effects company next to ILM. I don`t want to become extinct like the dinosaurs in JURASSIC PARK."7 Though relatively new, the company already had two major film credits with Cameron`s TRUE LIES (1994) and the all-star adaptation of INTERVIEW WITH THE VAMPIRE: THE VAMPIRE CHRONICLES (1994).

"They were looking for an effects facility," James Cameron said about GODZILLA. "It was just a huge job. They came to Digital Domain; we were bidding against a number of other people. We were awarded the work. It was a huge negotiation: a big deal, a lot of money."8 In October 1994, Digital Domain was signed as the primary visual effects supplier for GODZILLA. The company was given six months lead time to develop the new software programs needed to create the film`s extensive digital effects. "A lot of the effects haven`t been done before, so we have to design new software for it, and it`s rather complicated," Jan De Bont said.9

While Digital Domain would tackle the lion`s share of the digital workload, their previous feature film assignments had been 104 digital shots for TRUE LIES and 42 for INTERVIEW WITH THE VAMPIRE, far less than GODZILLA would require. Cameron admitted, "We didn`t want the whole job; we figured out a way to do part of it and supervise the work of two other smaller visual effects companies. There were 500 shots; they were all computer graphics animation."10

Shermis selected Sony Pictures Imageworks and VIFX to handle a number of shots. Both companies had worked with him and De Bont on SPEED, and Imageworks had been angling for the job even before the director and his team were hired, producing a CGI test using Jeff Farley and John Hood`s Godzilla maquettes. Sony Pictures Imageworks` Tim McGovern (TOTAL RECALL, LAST ACTION HERO, THE GHOST AND THE DARKNESS) and John Nelson (TERMINATOR 2: JUDGMENT DAY, GLADIATOR, IRON MAN) would supervise their studio`s work on GODZILLA.

Founded by Richard Hollander in 1988, VIFX was -- at that time -- the lead digital effects company for 20th Century Fox. In addition to SPEED, the studio produced effects for FREDDY`S DEAD: THE FINAL NIGHTMARE (1991), TIMECOP (1994), FROM DUSK TILL DAWN (1996), BROKEN ARROW (1996), VOLCANO (1997), FACE/OFF (1997), ALIEN RESURRECTION (1997), TITANIC (1997), THE X-FILES movie (1998), BLADE (1998), and ARMAGEDDON (1998). In 1999 Fox sold off VIFX to Rhythm & Hues Studios, and the company remains an active supplier of digital effects with credits on the X-MEN films, LORD OF THE RINGS, THE RING (2002), SERENITY (2005), THE CHRONICLES OF NARNIA: THE LION THE WITCH AND THE WARDROBE (2005), SUPERMAN RETURNS (2006), THE INCREDIBLE HULK (2008) and THE WOLFMAN (2010).

"What I remember most about GODZILLA is a series of meetings at Digital Domain," Richard Hollander told SciFi Japan. "There were three digital effects companies involved, and we had several discussions about how to split up the scenes between them. This was an exciting time, and we were looking forward to taking the next step with digital effects. This was right after JURASSIC PARK, so a realistic living creature could now be done. The tough areas were in creating believable scenes of destruction -- crumbling buildings and debris -- and water effects. Rendering water digitally was extremely difficult and time-consuming. Water is still hard to do today, but it was even worse back then. In terms of difficulty, the easiest would be creature effects, then destruction, then water. I was hoping to get the water scenes for GODZILLA."

Hollywood saw digital effects as the wave of the future, and the competing FX studios were fiercely protective of their talent and technology. But the GODZILLA assignment would require rivals Digital Domain, Sony Pictures Imageworks and VIFX to share computer software. A 1994 article in The Hollywood Reporter quoted an unnamed source as saying, "It`s hard to believe this is going to work. First of all, these companies all hate each other!" But Hollander clarified that discussions between the three were, if understandably cautious, generally positive: "There was a lot of talk about scenes where sharing technology might be necessary and how that would be handled." Boyd Shermis agreed, saying that everyone involved at Digital Domain, Sony Pictures Imageworks and VIFX were willing to step up, "To set a new standard for action, creature animation, destruction and water simulations."

For a brief time, adding a fourth digital effects company was also considered. Shermis reported that, "PDI [Pacific Data Images] was in the mix, but was in the midst of being sold to DreamWorks Animation and backed out of working on GODZILLA." PDI turned down GODZILLA, in part, to sign as the lead effects provider for director Renny Harlin`s pirate movie, CUTTHOAT ISLAND, at Carolco Pictures. The CUTTHROAT visual effects crew were pleased, with one staff member noting that, "GODZILLA was threatening to gobble up every effects house on the planet." But, Harlin had a change of heart, scrapping major digital effects sequences in favor of building and filming on full-scale pirate ships. PDI struggled in the wake of losing the CUTTHOAT ISLAND contract, but rebounded after being acquired by DreamWorks Animation. Now known as PDI/DreamWorks, the company has produced several hugely successful computer animated features, including the SHREK, MADAGASCAR, and KUNG FU PANDA franchises.

De Bont was impressed by the qualities original Godzilla suit actor Haruo Nakajima brought to the character in the Toho films. Photo courtesy of Daisuke Ishizuka.

De Bont was impressed by the qualities original Godzilla suit actor Haruo Nakajima brought to the character in the Toho films. Photo courtesy of Daisuke Ishizuka.Even though traditional Toho suitmation would not be used for Godzilla and the other monsters, Jan De Bont still intended for actors to provide much of their performances. "The motions a person can make that you transfer to a creature, it gives the creature a little bit of heart and soul," he asserted. "You cannot do that just technically. None of it really comes to life. I felt they didn’t do that [in TriStar`s 1998 GODZILLA] and missed some of the magic that Godzilla should have."

While visiting Toho in Japan, De Bont had met with both original Godzilla suit actor Haruo Nakajima and the 1980s-1990s Godzilla, Kenpachiro Satsuma. "I loved the old guy [Nakajima]," he recalled. "He’s really nice... such a great guy. He showed me all the locations and talked about how little time he could spend in the suit because he was melting from the heat. It was like an oven inside." "What I loved about him was that his movements are real. He told me he really studied Godzilla and it took him two movies or so to get it right. He was very proud of his performance."

De Bont wanted to use motion-capture to bring that type of performance to his Godzilla. "The men in the suit have some very endearing qualities that you kind of lose with CGI. In that regard, when people are using actors to play the monster and then later translate the actor’s feelings to the monster you have a much better chance of doing that. And that’s what we kind of planned as well." "We were doing some tests for motion-capture," he explained. "And we talked to many people about the best way to do that. At the time, it was very effective, actually... like in the silent movie period, actors would have to tell a story with the movement of their arms and facial expressions, and people understood the story. Godzilla can’t talk either -- he can scream, he can roar -- therefore, the idea that an actor can portray that and then transfer that performance to the creature via motion-capture would be very, very beneficial and effective."

"There were two companies -- I don’t remember their names anymore -- who were at the forefront of that, and those people were all very excited about it. Everybody was excited by the possibilities. Of course I had to show them all the movies of Godzilla so they understood what I was talking about. They really got a great sense of Godzilla as a character. It was fun."

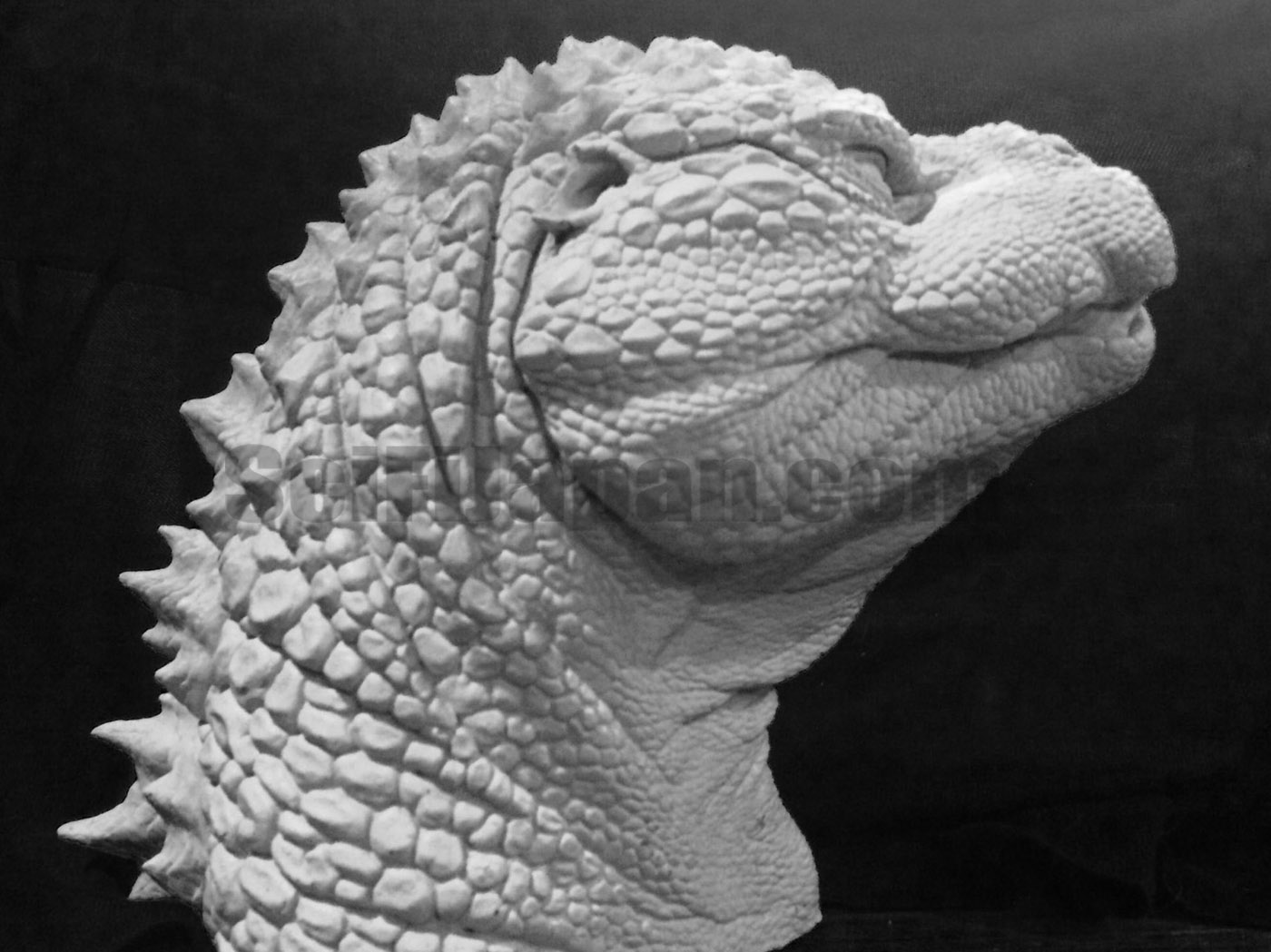

Unpainted Godzilla maquette from Stan Winston Studio. Photo courtesy of Jan De Bont. © Stan Winston Studio © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.

Unpainted Godzilla maquette from Stan Winston Studio. Photo courtesy of Jan De Bont. © Stan Winston Studio © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.CONCEPTUAL DESIGN, ROUND TWO: WINSTON STUDIO

"Redoing something that’s a classic; there’s a lot riding on that. A lot of people are going to be watching to see what you do, that you don’t change it." --Stan Winston Studio Godzilla sculptor Joey Orosco

"We all just wanted to do it `right`. Toho had the final right to review the designs, but we were in control of it." --GODZILLA (1994) FX supervisor Boyd Shermis

Stan Winston poses with his creation, Pumpkinhead, while the Winston Studio Godzilla maquette lurks in the background. © Stan Winston Studio

Stan Winston poses with his creation, Pumpkinhead, while the Winston Studio Godzilla maquette lurks in the background. © Stan Winston StudioAs one of the founders of Digital Domain, Stan Winston was also able to secure the GODZILLA concept design assignment for Stan Winston Studio. His team took over the process of developing the final looks for Godzilla, the Probe Bat and the Gryphon from Jan De Bont`s in-house design crew of Ricardo Delgado and Carlos Huante. Winston Studio was also tasked with sculpting maquettes that would be scanned by Digital Domain to build the digital versions of the monsters, as well as building any puppets, props, suits or mechanical incarnations of the beasts that may be used in conjunction with the computer generated versions.

"They were totally excited about working on this movie," Jan De Bont recalled. "We all felt that way," said Joey Orosco, a lead character designer and sculptor who has worked on the JURASSIC PARK series, INTERVIEW WITH THE VAMPIRE, THE SIXTH SENSE (1999), AVATAR (2009), PREDATORS (2010), MEN IN BLACK 3 (2012), MAN OF STEEL (2013) and PACIFIC RIM (2013). "The first time [creature effects supervisor] John Rosengrant talked to me about it I was like, ‘Oh my gosh, this is cool. I’m so excited’. I know that Stan had Digital Domain going, that was really fresh and new. And I remember him getting really excited about getting both gigs on GODZILLA; Stan would be handling the makeup effects and -- as part owner of Digital Domain -- the CG as well. It would have been great."

While the studio was known for their large-scale creatures, FX director Boyd Shermis was unconvinced that the technique would work for GODZILLA. "For what it`s worth, Jan and I both wanted to keep Stan Winston Studio`s involvement to a bare minimum," he insisted. "We both believed in the CGI and neither of us were happy to see `puppets` be used. Godzilla was just too huge as a creature to go with animatronics."

Joey Orosco in Hawaii with his Triceratops from JURASSIC PARK. Photo courtesy of Joey Orosco. TM & © Universal Studios and Amblin Entertainment

Joey Orosco in Hawaii with his Triceratops from JURASSIC PARK. Photo courtesy of Joey Orosco. TM & © Universal Studios and Amblin EntertainmentBut Joey Orosco felt Winston`s involvement would almost guarantee the use of animatronics. "I would definitely say ‘yes’ because you’re talking about Stan Winston and we were really rolling at that time from JURASSIC PARK. There’s nothing like bringing something live, right there, that the actors can touch. I had done the sick Triceratops -- that was my thing -- and there was nothing cooler for the actors, Laura Dern and everybody, than to be right there with the triceratops and interact with it. Stan would have done some live stuff for GODZILLA."

Jan De Bont agreed, noting that his first meetings with Stan Winston were over the feasibility of doing mechanical creatures. "We were going to do some animatronics," he said. "For some of the facial things, we were thinking about building just the head to control some of the motions even more smoothly. And we definitely had some of Stan’s artists working on it and they came up with some ideas. The question was the scale of it... they had never worked on such a big scale and that’s always a little bit problematic. The bigger the creature is, the harder it is to make it move in an organic way, as if it has life."

"It was going to be a combination of quite a few different things. It would have been better than a fully CGI movie because, if you use animatronics and film it right and find the right filming speed [to create a sense of size and mass], it can be very dramatic. It’s hard to do those things because you don’t know what you can do with the animatronics and what motions you can make until you actually have the machine working. So we were never thinking about doing the whole creature. It was always going to be the head, the claws... sections for when we had to get closer in and make it look more real. I don’t recall the exact scale, but it would look real."

Stan Winston Studio photo of the Godzilla maquette. Photo courtesy of Stan Winston School of Character Arts. © Stan Winston Studio © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.

Stan Winston Studio photo of the Godzilla maquette. Photo courtesy of Stan Winston School of Character Arts. © Stan Winston Studio © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd."I know Stan would have done an insert head or an insert foot; maybe an insert arm or even a big mechanical part of a tail swinging," Orosco added. "Stan definitely would have thrown in some mechanics. Not full scale, but maybe something like one quarter scale... a highly detailed mechanical head that would have been shot with green screen or blue screen."

The designing and sculpting of Godzilla and the other characters would be handled by the Winston art department under the supervision of John Rosengrant and Shane Patrick Mahan. It was a team effort, with different personnel chipping in as needed. "When a job came into Stan`s, the first thing that would happen is a group of artists would start sketches for designs. This was back in pencil and paper days," remembered Bruce Spaulding Fuller, a member of the Winston Studio art department.

Fuller described the maquette-making process: "Larger maquettes start by having the artwork blown up to size. Then the mechanical department would weld a steel armature together that would come apart at all the joints for ease of molding later. Then the sculptor or sculptors would work over that. On large maquettes like these it was customary for two or more people to work on the sculpts, especially finishing parts when they were broken off the main sculpt."

Once the maquettes were approved by Jan De Bont, they would have been scanned by Digital Domain to build the computer generated versions of the monsters. Closeup photos of the sculpts would be taken to match skin textures and colors in the CG models, and texture maps would be done for all surface details. From there Digital Domain would have created supporting understructures of bone and muscle that would guide the movements of the creatures.

Meanwhile, the mechanical department run by Richard Landon and Craig Caton-Largent would develop and construct the large-scale animatronic versions of the monsters. De Bont commented that, "It never got to the animatronics stage but they did do designs for the creatures."

From left to right: Bruce Spaulding Fuller, Ken Stoddard, David Monzingo, Jim Charmatz and Mike Smithson.

From left to right: Bruce Spaulding Fuller, Ken Stoddard, David Monzingo, Jim Charmatz and Mike Smithson.Details on the GODZILLA design crew were provided by Winston artist David Monzingo. "Here`s what I can remember: Crash [Mark McCreery] did all of the concept designs, Joey Orosco sculpted Godzilla and was assisted by Scott Stoddard, Mark Maitre sculpted the Gryphon and was assisted by Scott Stoddard and maybe Jim Charmatz. Bruce Spaulding Fuller sculpted the bat creature and was assisted by Ken Brilliant and Jackie Gonzalez. There were probably some mold makers and other art department fellows like myself who helped out along the way but weren`t necessarily key to the process..."

Photo courtesy of Paul Mejias. © Stan Winston Studio © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.

Photo courtesy of Paul Mejias. © Stan Winston Studio © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.The crew`s focus was on creating the monsters, leaving the alien probe and any prop designing for a later date. "I don`t recall any of those other things being designed. We just concentrated on Godzilla, the Gryphon and the Probe Bat. We weren`t designing the other elements in the script so the project was likely not a full green light yet," said Fuller.

The team sculpting the Godzilla maquette was led by Joey Orosco. "I believe Crash did a finished design before Joey sculpted his maquette, and Joey worked from Crash`s drawings, but I could be wrong," Monzingo remarked. "I wasn`t involved in the concept meetings with Stan, so I can`t say who came up with the look, whether Crash did or if Stan had much input. I know Joey interpreted Crash`s design, and while it`s close, Joey has a very distinct style of his own."

Joey Orosco explained that, "Crash was brought on to try and sell the idea and get it into the shop, which worked because his drawings are so amazing. Once we got that, we had a meeting with Stan, John Rosengrant and everybody and we talked about trying to stay traditional and just bring it to life. I remember Stan specifically saying that, ‘Just bring it to life’. And I loved komodo dragons and monitor lizards and certain snakes and thought we could bring that reality to Godzilla. Just update it a little bit, y’know?" “Redoing something that’s a classic; there’s a lot riding on that. A lot of people are going to be watching to see what you do, that you don’t change it. That’s a challenge. It’s easier to create something new and fresh.”

Brian Gilbert, an executive at Stan Winston Productions, succinctly noted that, "We wanted Godzilla to look like Godzilla, not some stupid lizard." Boyd Shermis added, "We all just wanted to do it `right`. Toho had the final right to review the designs, but we were in control of it."

Contrary to reports, the new designs were not based off the Godzilla and Gryphon artwork Ricardo Delgado and Carlos Huante had produced before Winston Studio signed on. Asked if he had seen the earlier designs, Crash McCreery replied, "I don’t know if I saw Carlos’ stuff, but I saw Ricardo`s and thought it was really cool. I didn’t see it until after we were done, and it was by chance... it wasn’t presented or sent over [to the studio] or anything like that. We hadn’t seen anything at all when we were working on GODZILLA."

"It’s funny because Ricardo and I graduated from Art Center around the same time and we’d been watching each other’s work. And I’d seen his Age of Reptiles stuff. I just remember his Godzilla pieces having a very cool energy and dynamic attitude. They were another cool version of what you can do with Godzilla."

"But the two designs never collided. We never really got any ideas from anyone else; we just went off and did our own thing. Stan really liked to leave his mark -- it was his signature -- so he would let us go off, do our own thing, and develop it in-house without the influence of anything else that had been done before so that he could really call it his own. He had a lot of pride in our work and his work in that manner. It wasn’t that he was keeping it from us for any reason other than just wanting us to be free to do what it is we love to do."

Front and back Godzilla turnarounds by Mark McCreery. Image courtesy of Stan Winston School of Character Arts. © Stan Winston Studio © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.

Front and back Godzilla turnarounds by Mark McCreery. Image courtesy of Stan Winston School of Character Arts. © Stan Winston Studio © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.McCreery was pleased for the opportunity to present his take on the Godzilla movies he had grown up watching. "I was always a huge fan, and obviously of monster films in general, but I never viewed Godzilla films as ‘monster movies’, for some reason. The very first one with Raymond Burr I thought was very cool and I remember seeing that and going, ‘wow, that was kind of scary’. But I’ve never been afraid of giant monsters... ghost stories always creep me out but never large monsters. I always equated that to dinosaurs, and dinosaurs are just cool."

"My friend and I used to watch them all the time and just get into all the different names of the monsters. I kind of got the humor in them; there’s a campiness to it that grows on you. And even the films after awhile, especially when [the Son of Godzilla] was introduced, its like, ‘okay, we get it’. We enjoyed it, but it was always in a different category for me growing up. I separate Godzilla even from TARANTULA or THEM or even THE BEAST FROM 20,000 FATHOMS. For me, those were just bitchin’ FX films that were really trying to sell you on the idea of the reality of something like that happening. And Godzilla, to me, was much more mythological and fun. It was in Japan, and the words didn’t match the lips, and you could tell they were guys in suits and you could see the wires. There was something really cool about it, but in a completely different arena than those other large creature movies. And as kid you either love them or you just don’t. And I loved watching them."

"Those creatures do become characters over time. And they’re revered in Japan as mythological beings that have something to do with their culture. Growing up, Japanese culture was so foreign to me but I kind of got it, in a weird way. You kind of accept them as being figureheads of a culture, and even though I didn’t participate in that culture you appreciate them for being that. So I was very lenient [over any technical flaws] because this was cool to them, and it was cool to me. I’ve always embraced that attitude."

Godzilla profile by Crash McCreery. Image courtesy of Mark McCreery and Stan Winston School of Character Arts. © Stan Winston Studio © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.

Godzilla profile by Crash McCreery. Image courtesy of Mark McCreery and Stan Winston School of Character Arts. © Stan Winston Studio © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.McCreery started by drawing a profile view of Godzilla. "Joey was overseeing the sculpt, and that profile was sort of a basis for Joey to go off of. That’s what I had done on JURASSIC PARK for the modelers; give them something to base the maquette off of," he said. "It’s interesting because I had visions of Godzilla from when I was a kid watching him, and you respect the character and the design for what it is and you don’t really examine it until you’re going to remake it. And then you really look at what was going on with design elements like how big the tail was… as soon as you reduce something like that, it doesn’t become Godzilla anymore. So there were a lot of characteristics about the original Godzilla that, unless you retain them, it’s really not that character anymore."

Both McCreery and Orosco wanted Godzilla`s dorsal fins to retain the basic shape seen in the Toho films. Photo courtesy of Paul Mejias. © Stan Winston Studio © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.

Both McCreery and Orosco wanted Godzilla`s dorsal fins to retain the basic shape seen in the Toho films. Photo courtesy of Paul Mejias. © Stan Winston Studio © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.Eschewing scientific accuracy in favor of aesthetics, Crash McCreery`s Godzilla stood in a more upright position than current paleontological views on dinosaurs dictate. Rather, the creature`s posture remained closer to that of the original Godzilla and other monsters from the Toho movies. "Standing very upright, which is a very Charles Knight, old school way of thinking about dinosaurs where the legs and torso are more upright -- which made total sense since it was a guy in a suit in the original -- trying to make that feel real and natural was really difficult. As far as the face went, the detail was kind of easy for me because I wanted to give it a scaly texture, a lizard texture. And also enhance the dorsal fins; make them feel more bone-like, some kind of real world texture that you can relate to. Maintaining the silhouette was important; whenever you see those fins you know who that is."

"Godzilla’s skin texture was always kind of odd to me. It was always very nondescript, more of a texture without referencing any kind of animal. I tried to make sense of that texture on Godzilla. I also added a contrast between its belly and its back, just to give it a little more interest. And more detail in the head; again, trying to make it feel a little more naturalistic."

McCreery was very pleased with Joey Orosco`s interpretation of his drawings. "Every artist had their style, their strong points. What’s great about a collaborative effort is that you start off with something that’s the jumping off point, and once you get to 3D you try to retain whatever works because that’s what either the studio or Stan has seen and wants. Whatever spark that got them excited about it, you want to maintain that. Sometimes Stan would be rigid about following the designs and other times he’d want someone to be free to do their own interpretation. What you don’t want to do is show [a director or producer] your design -- Hey, here’s our design -- and then show up later with something that doesn’t look anything like it."

Closeup look at the detailing on Godzilla`s skin. Photo courtesy of Paul Mejias. © Stan Winston Studio © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.

Closeup look at the detailing on Godzilla`s skin. Photo courtesy of Paul Mejias. © Stan Winston Studio © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd."But then you quickly find out things that don’t work, that you’ve haven’t explored in 2D, that rear their ugly heads," he said. "And any change that Joey’s ever made, I’ve always looked at as being an improvement. Joey’s sculpting always took what worked from my designs and then whatever worked from his point of view and style, and integrated that as well. And it always seemed to develop into its own thing, a little bit of everybody, which is cool. It was a very cool, collaborative atmosphere.”

One reason that Mark McCreery and Joey Orosco worked so well together on Godzilla was that each had a similar design approach to the character. Orosco asserted that, "Since I was the head sculptor on that I definitely wanted to keep the classic silhouette... I didn’t want to lose the silhouette. I loved the way that it was upright and the way the tail looked composed to the body, the head, even the posture of the arms and how the shoulders are positioned. I tried to keep all of that the way it was. Even though it was a man in a Godzilla suit back then and this was probably going to be a mechanical thing we were going to build and a lot of CG, I still wanted to keep that look."

"Godzilla has such an iconic silhouette, it was real important for us to try and maintain," agreed McCreery. "Other iterations since have been great endeavors and certainly have qualities of their own that I’ve always been impressed by, but I’ve never felt like it was the Godzilla we’ve all grown up to know and love. But that’s what’s great about filmmaking; it’s always interpretations, a director’s vision or a producer’s vision. That’s what makes it interesting. And that’s what makes ours special, too. That was its own idea of how you could redo Godzilla. There’s a lot of different ways you could redo it."

The artists also felt that the proper tail length in proportion to the body was essential in maintaining the

The artists also felt that the proper tail length in proportion to the body was essential in maintaining the Orosco disclosed that, before starting his sculpt, he closely studied the Toho Godzilla design. "We took measurements. We had photo blowups of the original Godzilla and we wanted to make sure the tail length compared to the body on the maquette was really close to what it was [on the original]. And with a lot of lizards and komodo dragons the tails are almost longer than the torso, so you have to nail that and make sure the tail is very, very long for balance."

Orosco also revealed that Winston Studio was not allowed to do an exact copy of the Toho Godzilla design. "I remember also that we could not sculpt the `Godzilla` Godzilla," he reported. "For rights reasons, we couldn’t just take the original Godzilla and do that completely. It could not be a spot-on match. It was important that we make sure it was an original, new design based on [Toho`s version] but not a copy. They own the rights to that look and we just wanted to give a version of that. That developed pretty easily. We just started sculpting and it came to life pretty fast. It was tough, but it was fun. After JURASSIC PARK, getting to dive into GODZILLA was fun. We were ready."

The finished Godzilla maquette measured 43 inches tall x 63 inches long. "A sculpt that big lends opportunity for the crew to jump in and put their hands on something," said McCreery. "Some of the sculptors had help... not that they couldn’t have done it themselves but there may have been a time constraint or just giving somebody the experience to get their hands on a sculpt. And if there was any kind of discrepancy Joey would pull me in and say, ‘What do you think of this?’ And if I didn’t know, then we’d pull Stan in and he’d make the final decision as the ringleader."

Paul Mejias and his Parasaurolophus sculpt from the JURASSIC PARK films. Photo courtesy of Paul Mejias. TM & © Universal Studios and Amblin Entertainment

Paul Mejias and his Parasaurolophus sculpt from the JURASSIC PARK films. Photo courtesy of Paul Mejias. TM & © Universal Studios and Amblin EntertainmentJoey Orosco had difficulty remembering exactly who he had worked with on the maquette. "It’s been 21 years and we lost the show; GODZILLA never happened. And at that time we had so much stuff coming in from studios. We were just swamped with work with movies coming in and we were just constantly doing stuff. As we were finishing a show there were two others starting. It’s been so long I don’t remember too many other guys that were on it. I do remember Mark Maitre sculpting the arms with me... he was right next to me. And Paul Mejias also worked on it."

Paul Mejias is a key artist, sculptor, puppeteer, and animatronic puppet effects coordinator whose credits include TERMINATOR 2: JUDGMENT DAY, JURASSIC PARK (for which he had sculpted the Gallimimus for the herd stampede scene), IRON MAN and THE AVENGERS (2012). He remembered the people he worked with on GODZILLA and took photos of the finished maquette, but drew a blank when asked about his own role on the project. "Sorry man, I have zero recollection of working on GODZILLA... none," Mejias said. "I`m sure I did something, but it wasn`t memorable. In those days shows were flying through the studio at lighting speed. Alas, memory fades."

Bruce Fuller confirmed that, "Paul was there at the time, but I have no idea what he contributed. Likely he helped one of us finish some sculpting... most likely when parts were broken off the main sculpt to have finished detailing before mold."

Clearing up the mystery, Orosco said, "I think Paul may have been on some of the spikes. We made sure that those fins were very spiky, almost Christmas tree-ish. That was one of the things we talked about, we wanted to make sure that you could see the spikes on those fins."

Godzilla foot detailed by Mike Smithson. Photo courtesy of Paul Majias. © Stan Winston Studio © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/Toho Co., Ltd.

Godzilla foot detailed by Mike Smithson. Photo courtesy of Paul Majias. © Stan Winston Studio © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/Toho Co., Ltd.Orosco`s team also included special effects makeup artist/sculptor Scott Stoddard (THE LOST WORLD: JURASSIC PARK, THOR) and sculptor/puppeteer Ken Brilliant (EVIL DEAD 2, BATMAN RETURNS, SHARKNADO). "Yes, I can confirm that I did work on the Winston Godzilla," Brilliant told SciFi Japan. "I was one of several people who sculpted on the design maquette, which was large -- perhaps three feet tall. There were a number of people working on it at once."

Another member of the crew was Mike Smithson, a special makeup effects artist whose credits include AUSTIN POWERS: THE SPY WHO SHAGGED ME (1999), SPIDER-MAN 3 (2007), STAR TREK (2009), AVATAR, THOR (2011), PIRATES OF THE CARIBBEAN: ON STRANGER TIDES (2011) and THOR: THE DARK WORLD (2013). "I really did not have much to do with the project," he related. "What I did do was sculpt and detail the legs and feet of the Stan Winston Godzilla maquette."

David Monzingo also gave an assist. "I really was just an extra set of hands on GODZILLA," he said. "I think I may have helped sculpt some of the back spines on the Godzilla maquette that Joey Orosco did along with Scott Stoddard, but to be honest I was working on every project that SWS was doing at the time as well I don`t remember having too much to do with it. It all kind of blurs together. I remember doing some Godzilla sketches of my own but none of them were ever used. I worked in the art department, but I was just a staff artist, not one of the key artists like Joey or Crash."

Even with so many talented artists involved, creating the Godzilla maquette took several weeks. "Nowadays we can rapid prototype something like those maquettes so it would be possible to make a character in only a few days," reported Monzingo. "But back then it took Joey -- who is a very fast sculptor, by the way -- at least a couple weeks to finish the sculpture, then another week or so to mold the sculpture, a few more days to cast it and assemble the pieces, and a few more days to paint it. So altogether it was probably at least a month. I believe Joey did two heads, one with the mouth closed and one with it open."

Two views of the neutral Godzilla head sculpted by Joey Orosco. Photos courtesy of Joey Orosco. © Stan Winston Studio © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.

Two views of the neutral Godzilla head sculpted by Joey Orosco. Photos courtesy of Joey Orosco. © Stan Winston Studio © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.Orosco confirmed that two different Godzilla heads were sculpted. "That was really big at the time, sculpting a neutral and what we call a `roar` head. I did that in GHOST AND THE DARKNESS with my lions and when I worked on gorilla films like CONGO and INSTINCT. You always do the animals with a standard head with the mouth a little bit open. And then you do a roar head, which is mid-open, slight expression, a little bit of wrinkling."

Photo courtesy of Joey Orosco. © Stan Winston Studio © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.

Photo courtesy of Joey Orosco. © Stan Winston Studio © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.The roar head was used for the maquette. The neutral head was cast separately in resin so Joey Orosco could do a paint test, but the project was canceled before that could be done. "I never got around to it," he said. Mark Maitre also worked on the sculpt and was closely involved in creating the fine details and skin texture of the figure. "Basically, Joey was in charge of Godzilla. He started detailing it, and then he had to go out of town on another project. So a bunch of us got together on Halloween night to finish up all the detailing on Godzilla," he recalled.

"I had to go to Costa Rica for CONGO," Orosco explained. "Stan had me doing everything. He was spreading me thin; it was pretty crazy. But there were so many talented guys and everybody got their share."

McCreery was there to give the detailing team the occasional assist. "Yeah, yeah, yeah, I remember that. He was pulled to Costa Rica and there was a mad rush... Godzilla had to be molded by a certain time so it was all hands on deck. They got to a point where Joey had left something that wasn’t shown in the drawings so I would do these little drawings of scale patterns for them or make suggestions like ‘bring this fatty tissue over here’," he said with a laugh. He left the detailing on the Godzilla maquette to others, conceding, "I did get into some sculpting [at the studio] but it was always very minor. I worked with Joey a little bit on JURASSIC, and with Chris Swift on RELIC, and I think that was about it. I did a zombie Terminator head that never made it into the film. I enjoyed it, but there were guys there who were way better at it than me so I’d rather just let people do what they do best."

Revealed at last! Mark Maitre`s maquette for the Gryphon. © Stan Winston Studio © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.

Revealed at last! Mark Maitre`s maquette for the Gryphon. © Stan Winston Studio © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.Following his assist on Godzilla, Mark Maitre became lead sculptor on the Gryphon. Maitre was another key artist and member of the creature art department at Winston Studio with credits on A NIGHTMARE ON ELM STREET 5: THE DREAM CHILD (1989), STARGATE, RELIC, THE LOST WORLD: JURASSIC PARK, A.I.: ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE (2001), THE TIME MACHINE (2002), UNDERWORLD (2003), PREDATORS, and PIRANHA 3DD (2011). "I got lucky, I guess," he said about getting the assignment. "Maybe the regular guys weren’t there. Joey would have been heavily involved if he were around the whole time. Thankfully, they trusted me and my abilities. Once Godzilla was done we started on the Gryphon."

Mark Maitre`s main partner on the Gryphon was Scott Stoddard. "Scott was on board with me the whole time on the sculpture. Mainly, it was just me and him doing the whole thing. I was blocking out the body and head, and Scotty came aboard and started blocking out the wings and the tail. And when he got done with that he was just jammin’ with me on the body, detailing it up."

"And it was nice that it was just a couple of us. I remember the problem we had on the Godzilla sculpture was that there were five or six guys trying to do all the detailing. I think everyone has a really interesting, distinctive style, like Joey Orosco, you can’t miss that... Bill Blasso, all those guys. And no two of us matched, particularly when we’re working late on a Halloween night to get it done. There’s an arm over there and Mike Smithson’s working on it; there’s a leg over there and Bruce Fuller’s working on it."

"So it was just Scotty and I on the Gryphon, and we work really well together... we have similar styles, you know? And I was glad I had him on board because it was a big, big piece. The wings were like 9 feet. I couldn’t tell you how tall the thing was because we had it built up on a table so we could work on it. I would think it was at least 4 feet tall." Joey Orosco was impressed with the Gryphon, saying, "It was a pretty big maquette. It was the size of a dog and we had it hanging up in the display room. It was really cool."

"Those were unusually large maquettes," Mark McCreery expressed about Godzilla and the Gryphon. "Back then we didn’t usually do maquettes that big because of the time consumption. I know Stan really wanted to sell the idea that these characters are bigger than life... to really get into the details, to really show what’s different about, what’s special about these characters we’ve enhanced for this go-round of Godzilla."

McCreery also designed the new version of the Gryphon. "Crash was designing Godzilla and the Gryphon and other projects [for Winston Studio], too, so he was swamped with everything," observed Mark Maitre. "But he had this cool drawing; kind of a front shot of the Gryphon roaring, standing up on his hind legs, and that was the main design we had to go by."

Taking a radically different approach than Carlos Huante had previously, McCreery focused on the concept of the Gryphon as an amalgam of the Earth animals it had absorbed. "Crash’s design was based off a mixture of different animals that evolved into what was the Gryphon," Maitre recalled. "It started as a sort of silver starfish that made its way onto the shore. I can’t remember all the things that it evolved from to make the Gryphon. A bat; that was the first thing... that was where the wings came from. A bird, a cougar and a bunch of different things so it’s got hooves, a cat face, and a crazy, almost reptilian tail."

"I thought it was a really fun challenge," said McCreery. "I like the idea of gryphons and it was an opportunity to do our version of that and kind of unify it. It wasn’t made up of a bunch of animal parts; it had the attributes of different animals but felt like a single species or beast. That was a lot of fun to work on. I went off of prehistoric cues to give it the crest on its head, the scales, and then pulled from mythological cues to give it the claws in the front and the hoofed feet in the back. I had a lot of fun with that; the fact that it has wings and hooves. I’m very much into textures and it offered a lot of fun opportunities."

Gryphon head profile artwork by Crash McCreery. Image courtesy of Mark McCreery. © Stan Winston Studio © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.

Gryphon head profile artwork by Crash McCreery. Image courtesy of Mark McCreery. © Stan Winston Studio © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd."The reptilian cat face was really fun to draw. The original Godzilla has a very catlike head, and I thought retaining that feel for the Gryphon as well would tie it in. And I loved the size of it, that Godzilla had a nemesis that was his size was cool. I think there was even a passage in the script where the Gryphon appears and -- this was pre-CLOVERFIELD -- it’s kind of perched on the Statue of Liberty, which was just a cool, cool image. I never got to draw that and it was such a fantastic image. I did do an orthographic (a "turn-around" drawing of the character showing the front, back, side and top) of the Gryphon as well as an attack pose, but that was as far as I got with that."

Maitre remembered that McCreery, "drew this other side shot for us so we could see the anatomy. As we were blocking it out he was finishing the design drawing so we were like, ‘Hurry up! We gotta detail this soon!’ But he was just swamped. I think he was working on the muscles for Godzilla and he had to get taken off the Gryphon. I was like, ‘Dude, finish this drawing!’ But I love working with Crash’s designs. I think every project I worked on when I was at Stan’s was a Crash design." "

That was so true," McCreery laughed about racing to finish the design for Maitre and Stoddard. "They’d go, ‘What goes on here? You didn’t finish that part’. It’s nice because we had a lot, a lot of talented artists there and it was always a great collaborative effort. And the fact that they wanted me to finish off the vision of what some of the areas looked like always made me feel pleased. That was always really cool." He added that, "The maquette really came to life, really captured the essence of the drawing. It was a great depiction of it."

Gryphon full figure profile artwork by Crash McCreery. Image courtesy of Mark McCreery. © Stan Winston Studio © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.

Gryphon full figure profile artwork by Crash McCreery. Image courtesy of Mark McCreery. © Stan Winston Studio © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.Another member of the Gryphon team was sculptor, moldmaker and painter Jim Charmatz. Charmatz has worked as an FX artist for two decades on such titles as CONGO (1995), THE LOST WORLD: JURASSIC PARK, GALAXY QUEST, JURASSIC PARK III, SKY CAPTAIN AND THE WORLD OF TOMORROW (2004), CONSTANTINE (2005), WAR OF THE WORLDS, AVATAR, and CLASH OF THE TITANS. For the Gryphon, he recounted, "My involvement is hard to remember actually, but I think it was primarily patching the separate silicone parts (arms & legs) onto the body and then painting it." Paul Mejias also remembered that Jim "did some repainting and repair work on the Gryphon several years after it was made for the display room at the Winston shop."

David Monzingo also assisted in the sculpting of the Gryphon. "I am very familiar with that character... I helped out on that way back when," he recalled.

Asked about the time frame for sculpting the Gryphon, Mark Maitre answered, "I couldn’t tell you how long we had. It was at least six weeks. Back then you had forever to do a sculpt and it still wasn’t enough time. These days you have a week or two. It’s such a blur."

"We made a silicon positive of the Gryphon. We had a really nice armature. Right after we sculpted it, Joey was back and he was working on the muscle structure of Godzilla. After the look of the outside skin is all detailed and molded, you pull the mold apart and what you have sometimes is the clay, sort of intact. Even if the surface comes off the majority of the sculpt is still there. [For the Godzilla maquette] they made a multiple piece sculpt that they could break away and shave the sculpt, and then Joey could sculpt down to get to the muscles. So he would take the actual sculpture, take away the skin, define everything to create the muscles."

Gryphon skeleton concept art by Crash McCreery. Image courtesy of Mark McCreery. © Stan Winston Studio © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.

Gryphon skeleton concept art by Crash McCreery. Image courtesy of Mark McCreery. © Stan Winston Studio © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.Orosco was surprised by Maitre`s recollections. "It’s been so long I can’t believe Mark remembers that. I sculpted an anatomy of Godzilla, and Stan said it was going to help the CG guys with movement. I’ve done that on several shows where I’ll do a sculpture, and then I’ll do a clay press and sculpt the anatomical structure of the muscles. For Godzilla, I took the original sculpt. When you take the mold off it’s still pretty intact, and I just took some tools and chiseled it down to the muscle layer. I found the anatomy and I carved the muscles to show how it functions. It’s great that Mark remembers that."

Maitre was looking forward to doing the same process for the Gryphon. "We were finishing up the Gryphon and I was going, ‘Oh great, we get to do the muscles next’. And then they said we had to stop working on it because the plug had been pulled and it was going on the shelf for now."

Bruce Spaulding Fuller`s Probe Bat design. Photo courtesy of the artist. © Stan Winston Studio © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.

Bruce Spaulding Fuller`s Probe Bat design. Photo courtesy of the artist. © Stan Winston Studio © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.Crash McCreery remembered the Probe Bats were also sculpted during that time. "There were these bat creatures that were part of the script as well. Another artist, Bruce Fuller, who had done some really great work... he designed those, which were really neat," he said.

Closeup on the face of the Probe Bat maquette. Photo courtesy of Bruce Spaulding Fuller. © Stan Winston Studio © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.

Closeup on the face of the Probe Bat maquette. Photo courtesy of Bruce Spaulding Fuller. © Stan Winston Studio © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd."I ended up in the film business because of my lifelong obsession with monster movies and comics," Bruce Spaulding Fuller declared. "As a youngster, once I figured out that a makeup man created these monsters, I began my quest to do the same using any small knowledge gleaned from monster magazines of the day like Famous Monsters of Filmland, and later Fangoria. In my young adulthood, I was the go-to guy locally to help my friends make horror movie trailers/showreels for films they wanted to make. Through these, I was fortunate enough to meet Edward French, a professional working in New York, and work with him on a few low budget horror pictures."

"From there I was `discovered` by [Academy Award-winning makeup artists] John Caglione and Doug Drexler and brought to California to work on DICK TRACY. Once I had a foothold in the California movie scene, I bounced around working for all the SPFX studios, and it was only a matter of time before I would work for Stan Winston. My first Stan Winston shows were PREDATOR 2 and EDWARD SCISSORHANDS and I was able to work in design, sculpture, paint, molds... essentially every aspect of the production of special effects."

Fuller recalled that, "Because of my ability to draw (from my love of comics) I was frequently tapped to be part of the design team. On GODZILLA, Crash McCreery was already designing Big G and the Gryphon himself, so that left the Probe Bat to work on. I don`t remember whether I was specifically assigned the Bat, but that`s what I was sketching ideas for when Jan De Bont came in to look at everything." He based his Probe Bat design on the descriptions provided in the Elliott/Rossio GODZILLA screenplay. "If I remember correctly it was an organism that assimilated many forest critters to become ambulatory and go out into the world. I believe -- this was a long time ago, remember -- that the final Gryphon was the sum total of this assimilation," Fuller said. "So the Probe Bat was a mish-mash of the things that had been assimilated up to that point... please don`t ask if I remember what they all were! I know there was bat in there! Possibly human, a cougar maybe? Who can remember..? I`m really not sure where the `snaky tail` with no legs idea came from, but it was what I was sketching when Jan De Bont decided that that was `IT!`."

Probe Bat artwork by Bruce Fuller. Image courtesy of Stan Winston School of Character Arts. © Stan Winston Studio © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.

Probe Bat artwork by Bruce Fuller. Image courtesy of Stan Winston School of Character Arts. © Stan Winston Studio © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd."I`m sure I had done some different things, but when De Bont came into the design room at Stan`s to see what we were doing, this version was the one I was sketching at the time. It was a very crude rough -- a gesture sketch, really -- but I guess there was enough information on the page for De Bont to see what he was looking for and proclaim this design to be the one. No one was more stunned than me; it`s extremely unusual for any design to be approved that quickly based on so little information. But De Bont was very sure, very definitive. From then on, it was my baby to flesh out and realize."

With Jan De Bont signed off on the design, Bruce Fuller began sculpting the maquette. "I moved right into the maquette without any final drawing being done for the Probe Bat," Fuller explained. "I worked on the Bat with the help -- I believe -- of Ken Brilliant... hard to remember." When asked about the Probe Bat, Brilliant replied: "I did work on the Godzilla maquette, but I don`t believe I worked on the gargoyle."

But David Monzingo said, "I remember Ken Brilliant sculpted on the wings of that bat creature." He added that Brilliant and another Winston artist named Jackie Perreault Gonzales (BRAM STOKER`S DRACULA, THE ISLAND OF DR. MOREAU, THE RELIC) each sculpted a wing of the Probe Bat. "Maybe Ken doesn`t want to remember because he took a very long time to sculpt his wing, and when he was finishing it up he dropped it on the floor and had to start over again!," Monzingo teased.

Photo courtesy of Stan Winston School of Profiles in History. © Stan Winston Studio © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/Toho Co., Ltd.

Photo courtesy of Stan Winston School of Profiles in History. © Stan Winston Studio © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/Toho Co., Ltd.But Jackie Gonzales was also sure she was not one of the scupltors of the Probe Bat. "Working at Stan Winston Studios was a wonderful experiences as a sculptor, but unfortunately GODZILLA was not one of the films I worked on," she insisted. "I think it may be possible that [David] is mixing up a couple of the creatures we worked on. Some aspects are similar to other pieces. I worked on the wings and body for Pteranodons for LOST WORLD -- someone may have adapted those wings or used a similar approach for making the Probe Bat wings. I also worked on some "mice men" for THE ISLAND OF DR. MOREAU which have similarly "rodent-y" face and arms as the Probe Bat. Though I must say, I think the Bat is more frightening looking! The sculptors there are so good! Wish I could take the credit, but nope."

The finished Probe Bat maquette was made of solid resin, measuring 45 inches long with a wingspan of 35 inches. "It’s small but it’s kind of neat. It had a crazy, monstrous-looking bat face," described Mark Maitre.

Bruce Spaulding Fuller noted that, "With the designs and then the maquettes, I`m going to say I was on GODZILLA a couple months. I can`t remember why at the time, but the project seemed to be on a fast track... whether the design work was to raise more funds, or it was just on a fast track to production, who knows?"

Asked about the accelerated schedule, De Bont told SciFi Japan, "The reason it had to be fast was that they were trying to find out, early on, what could be achieved with using Winston’s animatronics company. We were trying to figure out what would be the most effective and economical. CGI was getting there but it wasn’t perfect; it was still being fine-tuned. And CGI shots in those days were really expensive... people tend to forget that now. Especially if you wanted to do those shots in 4K, it was almost twice as much work because it had to be so perfect. And when there’s so many moving elements in one shot it becomes really important that one company does the backgrounds and another the animatronic element in the foreground... it would make it so much cheaper. But at the same time, will the looks ultimately match? If you mix them too much, would you still get something that feels real? That was my worry."

Profile views of the Probe Bat maquette. Photos courtesy of Profiles in History. © Stan Winston Studio © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.

Profile views of the Probe Bat maquette. Photos courtesy of Profiles in History. © Stan Winston Studio © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.David Monzingo recalled that some rough designs were done on yet another creature for the film. "Another artist who did some work on that project was a fellow named Greg Figiel. I remember he had a lot to do with some characters in the Jan De Bont version of GODZILLA." Figiel`s credits include ALIENS, TOTAL RECALL (1990), ROBOCOP 2 (1990), BATMAN RETURNS (1992), JURASSIC PARK, CONGO, THE LOST WORLD: JURASSIC PARK, GALAXY QUEST, PEARL HARBOR (2001) and ALIENS VS PREDATOR REQUIEM (2007).

Probe Bat scale chart by Bruce Fuller. Image courtesy of Jan De Bont. Stan Winston Studio © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.

Probe Bat scale chart by Bruce Fuller. Image courtesy of Jan De Bont. Stan Winston Studio © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd."Greg Figiel designed and I believe sculpted a maquette of a character that we never finished for the film," Monzingo revealed. "I can`t remember the character`s name, but in the film he was a human who has a microscopic alien organism enter his body, gets `infected`, then undergoes some `horrific` transformation into an alien. I remember it looked pretty cool, but I don`t think it ever got beyond a clay sketch... a very rough clay maquette that was never molded or finished. if I remember correctly it was a very thin, creepy looking thing."

"Yeah, that’s what I remember, too," said Crash McCreery. "That might have just come from Greg’s head. I think we weren’t getting a lot of heat from it so it started to peter out. Unfortunately, other things kind of took over. I don’t know if there was any 2D artwork done for it, but it was definitely part of the script. And that’s what was cool about the script, too, because it wasn’t just Godzilla. That’s what I loved about the old movies -- apart from the very first one -- just all of the other monsters and characters. And I felt like Jan’s version was really embracing that ‘Monster Island’ feel that was so awesome when I was a kid. That’s what I loved about it."

Stan Winston Studio was still at work on GODZILLA when TriStar canceled the project, so the artwork and maquettes produced up to that point were not necessarily what would have been seen in the finished film. "The creature designs were still evolving. Those were definitely not the final ones," Jan De Bont told SciFi Japan.

McCreery confirmed De Bont`s recollection, maintaining, "There’s usually a design process when it’s really going to happen and there’s a green light and real money is coming in and deadlines are set. The same thing happened in JURASSIC PARK where there was a T-rex design I had done that was that kind of mood piece, but then we really had to design the dinosaur. And that took a very long time to really hone in on what that was. I look at the design of Godzilla that we’ve done and there’s a lot of room for ‘okay, let’s change this, let’s change that, improve here, improve there’. And we needed to see it in five, six different poses so that we would know this design can achieve all of those. That’s where the real meat and potatoes come into designing a character. Unfortunately, I don’t feel like we ever got down that road."

While Winston had many other projects to fill their schedule, losing GODZILLA was still a major disappointment for all involved. "I still look back at that and go, ‘God, I wish we could have got that’," lamented Joey Orosco.

As a Godzilla fan, Joey Orosco was excited to work on the project and disappointed when it was canceled. Photo courtesy of Paul Mejias. © Stan Winston Studio © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.

As a Godzilla fan, Joey Orosco was excited to work on the project and disappointed when it was canceled. Photo courtesy of Paul Mejias. © Stan Winston Studio © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd."I was definitely a Godzilla fan," he elaborated. "It was something really big when I was a kid. I was a creature guy; I grew up loving the CREATURE FROM THE BLACK LAGOON. That was huge to me. Of course DRACULA and FRANKENSTEIN; all the great black and whites, and anything Lon Chaney did. PHANTOM OF THE OPERA just freaked me out. But GODZILLA was just huge for me, and so was THE WAR OF THE GARGANTUAS. They were amazing films to watch. I remember sitting there as a kid, Sunday mornings with a bowl of cereal, 8 years old watching these films on my old Zenith TV at my mom’s house. That was definitely a big part of my growth. Who would have thought that, years later, I would be sculpting Godzilla and almost working on one of those movies? It was close. I almost got to work on one of them."

“We tried to create something that was based on the traditional Godzilla that we all grew up with and loved,” Orosco declared. “We didn’t want to try and change it... we tried to keep it true to the original. A lot of films don’t do that these days. We tried to bring it to life, add some realistic elements from monitor lizards and komodo dragons to that but still keep the silhouette; keep the traditional look. Just bring some reality to it. I still look at it now and it has the posture, the face; even the dimensions from the body to the tail. I remember that we really studied that and try to give our Godzilla that feel. That was definitely our goal.”

Photos of the Winston Studio Gryphon and alien designs were never officially released, nor were any images leaked by the artists. "Back in those days Stan wouldn`t allow us to photograph our work... only the shop photographer could chronicle things," David Monzingo explained.

Nor did the artists keep their sculptures or artwork. "I don’t have a lot of stuff because it was basically owned by Stan," said Joey Orosco. "I was an employee; I was paid to do what I do and everything was owned by Stan. And a lot of it was actually owned by the production companies and the studios. When we were done with JURASSIC Universal owned the molds. That’s the way it was."

Photo courtesy of Paul Mejias. © Stan Winston Studio © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.

Photo courtesy of Paul Mejias. © Stan Winston Studio © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.When GODZILLA was revived under Roland Emmerich and Dean Devlin, Mark Maitre sculpted the Baby Godzilla for Patrick Tatopoulos Design, making him one of the few FX personnel involved with both versions of the TriStar film. "The weird part of the story is that I am very, very good friends with Patrick Tatopoulos, and before I worked at Stan’s I worked on STARGATE," he explained. "Patrick and I also worked on SUPER MARIO BROS. together and he got me involved with creating the Yoshi dinosaur back in ’93. A year went by and STARGATE happened, and that’s when Patrick wised up and said, ‘I’m gonna get a shop.’ He was giving out all this work to people like me and he realized, ‘I can make a lot more money if I just do that stuff here.’ So he opened a shop and started with STARGATE. I worked on that and met Greg Figiel, who was kind of a lifer at Stan’s... it was slow there at the time which is why he worked on STARGATE. He’s a real talented sculptor. He recommended me to Stan to partake in sculpting because they needed another crew to do TANK GIRL, which was the same time they were doing CONGO so they were swamped."

"Since I had the connection with Patrick before I worked at Stan’s, he called me up and said, ‘Guess what? I got GODZILLA’. And I was like, ‘Are you kidding me? We just lost it.’. He said he needed me to work on it and offered me maximum hours puppeteering, which means more residuals and goes towards your health coverage. That put me between a rock and a hard place since I’d been at Stan’s for two and a half years and he doesn’t like to let people go. So I brought it up to him and it was a very sore situation because he asked what I was going to work on. I said ‘GODZILLA’ and he goes `Uhhh!` He was a little sore that it was GODZILLA."

Closeup look at the detailing on Godzilla`s tail. Photo courtesy of Paul Mejias. © Stan Winston Studio © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.

Closeup look at the detailing on Godzilla`s tail. Photo courtesy of Paul Mejias. © Stan Winston Studio © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd."And after an hour of talking with Stan we left on good terms. He asked, ‘So what are you going to do in a year when GODZILLA’s over?’ I said, ‘I’ll come knocking on your door if you’ll have me back and it ended with ‘I’ll have you back.’ So I went away for a couple of years then I came back on A.I. I got to sculpt one of the main robots and worked on pretty much everything. It was a great comeback; I still love that movie to this day. I felt like, ‘Okay, I’m back!’." Maitre stayed with the Winston team, becoming part of Legacy Effects.

"It was home," Joey Orosco said of Stan Winston Studio. "You kind of get used to it because you work in a really cool place with dinosaurs and creatures everywhere. You get to wear what you want, play the music you want. And Stan always provided some great opportunities for newcomers. We gave a lot of chances to a lot of people. Get your feet in the door and work your way up, slowly. There were several, several people that came from schools and given internships. A lot of them succeeded and some didn’t."

David Monzingo was a product of Winston`s internship program, joining the studio in 1993. "I met Stan when he was promoting TERMINATOR 2," he recounted. "I interned at the studio in the summer between my junior and senior years of high school, then began working there full time on INTERVIEW WITH THE VAMPIRE."

Orosco added that, "There was so much stuff going on there that, no matter what, something was going to get put on your plate and whether you were able to devour it or not it was up to you. As long as you’re doing your job and making Stan happy it’s rockin’ creating great makeup effects. That’s what it was all about."

Photo courtesy of Jan De Bont. © Stan Winston Studio © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.

Photo courtesy of Jan De Bont. © Stan Winston Studio © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd. Closeup look at the model of the ice cave. Photo courtesy of Jan De Bont. © Stan Winston Studio © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.

Closeup look at the model of the ice cave. Photo courtesy of Jan De Bont. © Stan Winston Studio © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.FINAL PREPARATIONS: CASTING plus MINIATURE and PRACTICAL EFFECTS

"Godzilla will be the star." --Henry Saperstein

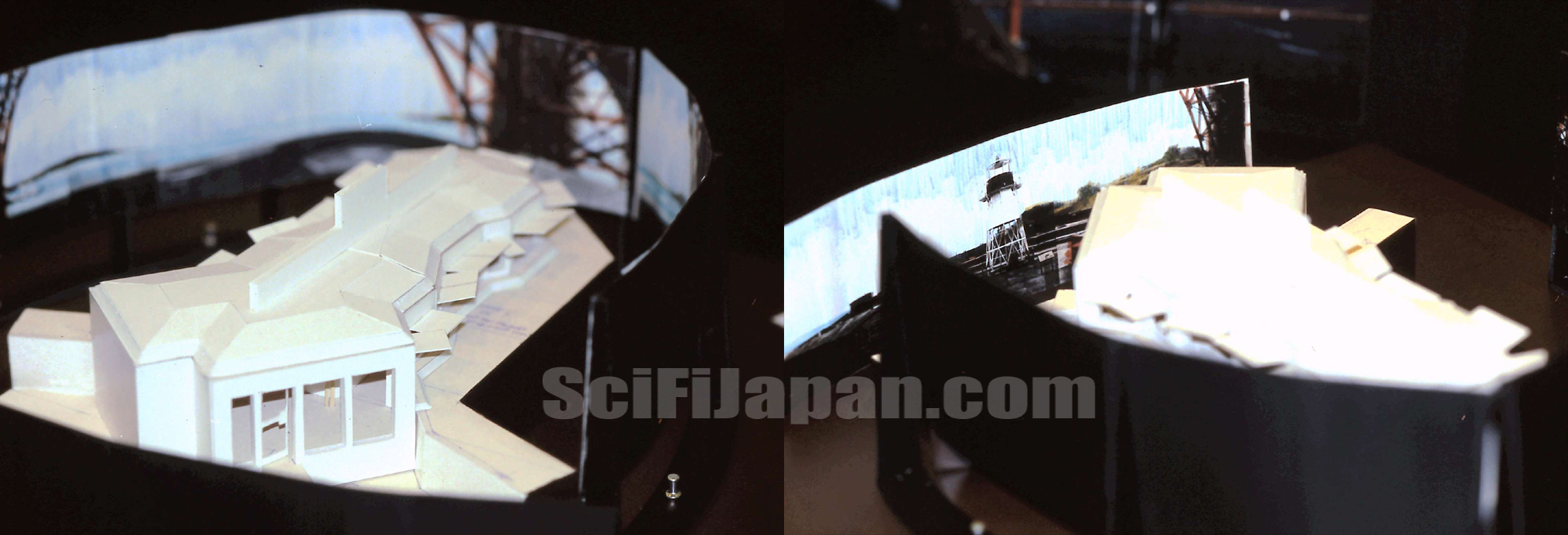

Beyond the array of digital and animatronic effects, GODZILLA would have required a number of shots involving miniatures. While negotiating with Digital Domain, the production team also began talks with Stetson Visual Services, Inc., the miniature effects company run by Mark Stetson and Robert Spurlock. Mark Stetson came to GODZILLA with an impressive resume that included models, effects props and miniatures for such films as STAR TREK: THE MOTION PICTURE, ESCAPE FROM NEW YORK, BLADE RUNNER, GHOSTBUSTERS, 2010 (for which he received an Academy Award nomination) and DIE HARD.

"I had little involvement with the Jan De Bont Godzilla project. I only attended a couple of meetings in the capacity of miniature effects provider," Stetson recalled. "Stetson Visual Services provided miniature effects services for Digital Domain on a few projects through 1994 -- THE COLOR OF NIGHT, TRUE LIES, INTERVIEW WITH THE VAMPIRE. Digital Domain invited us to bid the project with them."

While miniature sets and props were used extensively in Toho`s Godzilla movies, the American crew planned to take a much more limited approach. "I only recall that we were talking about set extensions of plates shot on location, and replacing key buildings for destruction. I think we also talked about creating vehicles in scenes for destruction, but that would have been very expensive," Mark Stetson explained. "There was no plan to create miniature scenes scaled to a `man-in-a-suit` Godzilla -- that approach was rejected by the filmmakers, obviously. So the use of miniatures would have been to create plates where a camera would not have been able to do so in a city environment, such as low-flying helicopter plates where such low flight is restricted in city streets, as well as action miniatures for destruction."

GODZILLA was canceled before Stetson Visual Services was awarded the assignment, so no sketches, blueprints or miniature work was ever done for the project. Mark Stetson and Robert Spurlock closed the company at the end of 1994, and Stetson became one of the film industry`s top visual effects supervisors. He won a British Academy of Film and Television Arts Award for THE FIFTH ELEMENT (1997) and both an Academy Award and a BAFTA Award for THE LORD OF THE RINGS: THE FELLOWSHIP OF THE RING (2001). Stetson was a visual effects consultant for the THE LORD OF THE RINGS trilogy and earned another Oscar nomination for SUPERMAN RETURNS (2006) before becoming head of feature films for the special effects company Zoic Studios (THE GREY, TWILIGHT SAGA: BREAKING DAWN - PART 2).

A major budgetary concern for the production were the film`s action sequences, many of which would require full-scale practical effects. A November 1994 Variety report noted: "Action sequence shots can cost anywhere from $80,000 to $140,000 per set-up. And with literally hundreds of set-ups being planned, it doesn’t take an Einstein to figure out the direction of the project’s spending plan, which could climb upwards of $100 million." An unnamed source said, "Like SPEED, they`ve just got some amazing stuff. Scene after scene of tunnels and buildings blowing up... flooding the Holland Tunnel."1

The larger scale, mechanical and practical effects for GODZILLA were assigned to Fxperts Inc (aka John Frazier Special Effects), founded by veteran visual effects supervisor John Frazier. Fxperts specializes in the engineering, manufacturing and operation of props and mechanical devices for films... their handiwork includes the full-scale Bumblebee built for the TRANSFORMERS movies, derailing locomotives for UNSTOPPABLE, hydraulic gimbles for the ships in PIRATES OF THE CARIBBEAN: AT WORLD`S END, the Armadillo all-terrain vehicles for ARMAGEDDON and exploding battleships for PEARL HARBOR. Frazier has been nominated for the Oscar seven times, winning in 2006 for his work on SPIDER-MAN 2.

For GODZILLA, Fxperts would create all the practical effects required for the film. Their work would involve anything from vehicles (rigged to shake, flip over or explode), to scenes requiring real fire or water, to gimbles for fighter jets to shots of crumbling buildings and sets. John Frazier also joined production designer Joseph Nemec in scouting expeditions to find suitable locations for the filming of full scale mechanical effects.

A key role for Frazier`s team would be supplying any pre-elements the CG artists would need for the visual effects shots. This would cover any visual information regarding how the actions of Godzilla and the Gryphon would affect their environments, allowing the digital effects crew to depict the monsters and their performances as realistically as possible onscreen. GODZILLA concept artist Ricardo Delgado said, "They really wanted to mesh the practical effects with the digital effects. I know they did tests to have a false Godzilla foot collapse a house."

"We did impact tests for how quickly Godzilla`s foot would come down as he walked or ran," John Frazier acknowledged. The crew spent a day dropping a large weight -- scaled to match Godzilla`s foot -- on cars, asphalt, and other surfaces. Frazier also noted that, "Two miniature buildings were constructed and smashed in Van Nuys. We also ran wave simulations and water tests."

Model of the Japanese fishing village, displayed with a Godzilla figure for scale. Photos courtesy of Jan De Bont. © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.

Model of the Japanese fishing village, displayed with a Godzilla figure for scale. Photos courtesy of Jan De Bont. © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.In November 1994, Frazier and other members of the crew traveled to Lone Ranch Beach in Brookings, Oregon to start construction on the first GODZILLA set; a full scale Japanese fishing village that would be featured in the very first sequence shot for the film. "It was a scene where Godzilla terrorizes a Japanese island in the Pacific," said Boyd Shermis. "It was really going to be in the movie, but we wanted to get started and to get the green light, so we called them tests."

Designed by Joseph Nemec and built under the supervision of John Frazier, the set would include buildings, a dock and other structures that would collapse and break apart as if being crushed by the monster. Nemec disclosed that, "Initial construction was started in that we did the site layout, ordered materials, and did some preliminary framing up of structures." The footage shot at the fishing village location would serve multiple purposes for the filmmakers. First, it would act as a test for the visual effects teams as both Godzilla and the effects of a powerful storm would be added digitally to the scene. The early shoot would give the FX crews ample time to create the finished shot and work out any kinks or glitches in their new software. The finished material would then be used for a teaser trailer to be released in the summer of 1995. Lastly, the full sequence would be included in the final cut of the film.