RING © 1998 The Ring/The Spiral Production Group. JU-ON: THE GRUDGE photo courtesy of Lions Gate Films. © 2003 Kadokawa Shoten Publishing Co., Ltd. DARK WATER photo courtesy of Buena Vista Pictures. © 2005 Touchstone Pictures. PULSE © 2001 Kadokawa Pictures

RING © 1998 The Ring/The Spiral Production Group. JU-ON: THE GRUDGE photo courtesy of Lions Gate Films. © 2003 Kadokawa Shoten Publishing Co., Ltd. DARK WATER photo courtesy of Buena Vista Pictures. © 2005 Touchstone Pictures. PULSE © 2001 Kadokawa PicturesAn Interview with Author and J-Horror Enthusiast David Kalat Author: John “Dutch” DeSentis Source: Vertical, Inc. Special Thanks to Vertical Inc., Eddie Stemkowski and Keith Aiken

Author David Kalat (l) with John DeSentis at New York Comic Con 2007. Photo courtesy of John DeSentis.

Author David Kalat (l) with John DeSentis at New York Comic Con 2007. Photo courtesy of John DeSentis.A SciFi JAPAN EXCLUSIVE

David Kalat is the author of several books, notably A Critical History and Filmography of Toho’s Godzilla Series. He has his own DVD company, All Day Entertainment, which specializes in restoring and presenting many old films that have not been seen in a long time. Last year he completed the audio commentary for Classic Media’s forthcoming DVD release of GHIDORAH: THE THREE-HEADED MONSTER. His latest project is the book J-Horror: The Definitive Guide to The Ring, The Grudge and Beyond which puts the focus on such Japanese films as JU-ON: THE GRUDGE, UZUMAKI, RING, DARK WATER and PULSE as well as their American counterparts. J-Horror was released February 27th by Vertical (the English language publisher of Japanese horror novels like Ring and Dark Water) and is now available from online retailers and in bookstores across America. David was on hand last weekend at New York Comic Con to host a presentation on Japanese horror films and promote his new book. He also sat down with SciFi Japan’s John DeSentis to talk about J-Horror and the history of the genre.

John DeSentis: Thank you for taking time to do the interview today. David Kalat: Thank you! JD: Obviously, fans of Godzilla and Toho films know you as the author of A Critical History and Filmography of Toho’s Godzilla Series. What have you been up to between the time when that book came out and now? DK: Well one of the bigger projects was that I launched a DVD company called All Day Entertainment. That actually got started ten years ago and we are celebrating our anniversary now. It’s been my opportunity to actually take these movies that I’ve been fascinated with that have fallen through the cracks and get them back out into the market place and hopefully give them a second life on DVD. So I’ve been doing a lot of work with film restoration and as an offshoot of that I was researching a group of movies that Fritz Lang and other German filmmakers have made over an eighty year time span about this character called Dr. Mabuse who is really kind of the negative image of James Bond. It was a very similar kind of pulpy spy story about a super criminal trying to take over the world. So I got some of those movies out on DVD and then wrote a book about them called The Strange Case of Dr. Mabuse which charted the history of that character. That was around the time when I saw THE RING and THE GRUDGE in their American form. I hadn’t seen the Japanese versions but I saw the remakes first and not only loved them as movies but was also fascinated at how the same images and same themes appeared in each movie yet worked independently of one another. The movies were completely solid, artistic statements on their own despite having so much in common. I found that interesting and went to the Japanese versions and saw even more similarities. The more I started to explore it, the more I began to think that J-Horror was something new under the sun. It was a different kind of movie genre than I had encountered before.

Two takes on a key moment in J-Horror: Reiko Asakawa (Nanako Matsushima) watches the cursed video in RING, and Rachel Keller (Naomi Watts) does the same thing four years later in THE RING. RING © 1998 Ring/The Spiral Production Group. THE RING photo courtesy of DreamWorks Pictures. © 2002 DreamWorks Pictures

Two takes on a key moment in J-Horror: Reiko Asakawa (Nanako Matsushima) watches the cursed video in RING, and Rachel Keller (Naomi Watts) does the same thing four years later in THE RING. RING © 1998 Ring/The Spiral Production Group. THE RING photo courtesy of DreamWorks Pictures. © 2002 DreamWorks PicturesJD: Well we’re here to talk about J-Horror, so let’s talk J-Horror. You mentioned in your introduction to the book and just now that you saw the American remakes of THE RING and THE GRUDGE before seeing the Japanese versions. Now that you have seen both, do you have a preference and what do you think of other American remakes like PULSE? DK: In terms of having a preference as far as THE RING and THE GRUDGE go, no I don’t really have a strong preference. What amazes me is that if you have somebody who is a fan of THE SEVEN SAMURAI and somebody who is a fan of THE MAGNIFICANT SEVEN, you’re going to have a really interesting argument over which one is better. You have a lot of material there to back up completely different views. Perhaps you are a fan of YOJIMBO and your friend is a fan of FISTFUL OF DOLLARS. You will have a lot to argue about.

JD: Well you got that; YOJIMBO is my favorite Kurosawa film. DK: Yeah, so you get the idea. I mean, I’m a fan of RING. I’m a fan of THE RING VIRUS [the Korean remake]. I’m a fan of the American version, THE RING. They’re almost identical. Now there are differences but those differences are so small and minute that by default you’re arguing over clones. I think that is really something. They’re not just remaking the story, they’re remaking the style. What matters is the presentation of it. JD: Does the fact that the American versions are so mainstream set them apart artistically from the Japanese versions? DK: Well American audiences definitely expect their stories to be linear and logical. Taka Ichise -who is the producer of the RING cycle of films, the GRUDGE, J-HORROR THEATER and other great horror films- when he was over here discussing the possibility of a remake of JU-ON [THE GRUDGE], American buyers were a little leery about how confusing Takashi Shimizu’s original film was. They said that American audiences would be baffled by this and he said that’s good, they should be. There’s no reason that a horror film should be logical. It has to be like a nightmare. The illogic is what makes it work. So there is that kind of cultural distance and that is why I think that films like DARK WATER and PULSE don’t, in my opinion, work as well as their originals because the American remakes explain too much. They are too linear. Take a look at the sequel to THE GRUDGE that just came out. I look at the movie and think that it is as logical, as coherent, and clearly explained as the other movies in the cycle yet the reviewers consistently thought the movie was baffling and impossible to follow. If they are going to go that far to explain it and maybe even go too far to explain it and the response is still to be that it is baffling I think that shows that there is some difficulty in selling these illogical plots to American audiences. I think that might continue to be an issue. JD: What is it specifically about THE GRUDGE and other American remakes that you enjoy so much?

J-Horror goes Hollywood: Japanese filmmaker Hideo Nakata directs Naomi Watts in THE RING TWO, the sequel to the remake of Nakata`s own RING. Photo courtesy of DreamWorks Pictures. © 2005 DreamWorks Pictures

J-Horror goes Hollywood: Japanese filmmaker Hideo Nakata directs Naomi Watts in THE RING TWO, the sequel to the remake of Nakata`s own RING. Photo courtesy of DreamWorks Pictures. © 2005 DreamWorks PicturesDK: Well, I am fascinated that it’s been since the 1960s that Japanese filmmakers have had access to an American audience and in the 1960s when there was a market for Japanese films in the U.S. you had, on one hand, movies by directors like Kurosawa and Kobayashi that would play at art houses. On the other hand, you would have Godzilla films which would be of more mainstream interest but they were still very much foreign films and appealed to a niche market. When THE RING and THE GRUDGE really started to open up the American market for its remakes of Japanese films that differed very slightly from their Japanese originals, what also started happening was that these Japanese filmmakers started getting access to Hollywood. They could come over here and make movies. Guys like Hideo Nakata, Takashi Shimizu, these guys are working in Hollywood now but you also get American investors for Japanese films. Some of the films being made there now for Japanese audiences are being financed by American companies so there is this intermingling of the two film industries that is really unprecedented. From an historical standpoint, I think that is fascinating. In terms of the effectiveness of the movies, I think that it’s great that there are movies like THE RING and THE GRUDGE that absolutely nailed it and I have no complaints about the way those movies were Americanized. Then there are films like DARK WATER and PULSE which I think they didn’t get the formula right.

Director Takashi Shimizu at work on Sony`s THE GRUDGE 2. Photo courtesy of Sony Pictures. © 2006 GHP 4-Grudge 2, LLC.

Director Takashi Shimizu at work on Sony`s THE GRUDGE 2. Photo courtesy of Sony Pictures. © 2006 GHP 4-Grudge 2, LLC.JD: Obviously you are a fan of Toho films. I’d like to ask you if you think J-Horror is a natural evolution from older, atmospheric horror films like MATANGO or is it a totally new breed? DK: Well J-Horror definitely draws a lot upon folklore and imagery which has been percolating around Japan and Asian countries for a long time but it’s doing it in a slightly different way. If you look at movies like KWAIDAN, ONIBABA, or THE YOTSUYA GHOST STORY, these are all classic ghost films that Japan churned out in the 1950s and 60s. You look at them and you see they are fairy tales, they are set the feudal past, and they have the same sort of other-worldliness that you would find in a samurai film whereas contemporary Japanese horror films are very much rooted in the real world. They’re about contemporary problems with real people and this sort of illogical, supernatural element coming into that real world setting. I think that is something that sets contemporary Japanese horror films apart from those of the past. JD: The image of the ghost woman with the long hair covering her face is a Japanese tradition. It seems that most American fans feel like the ghost in THE GRUDGE was ripping off the one from THE RING. I would like to get your thoughts on the old mythology behind that image.

Kayako (Takako Fuji) in THE GRUDGE. The deadly woman with long black hair is a traditional image in Japanese ghost stories. Photo courtesy of Sony Pictures. © 2004 GHP-2 Grudge, LLC.

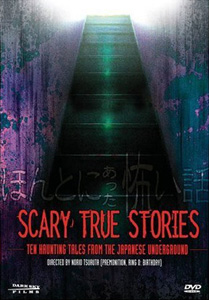

Kayako (Takako Fuji) in THE GRUDGE. The deadly woman with long black hair is a traditional image in Japanese ghost stories. Photo courtesy of Sony Pictures. © 2004 GHP-2 Grudge, LLC.DK: Well you’re right. The American media likes to tell the story that THE RING was a success and that everyone else came in and borrowed from that. However, when the original theatrical version of THE RING came out in 1998, Norio Tsuruta said “well I was just ripping off myself”. I was pointing that out because in fact Hideo Nakata’s version is actually a remake itself. The original was a made-for-TV movie from 1995 [RING: THE COMPLETE EDITION aka: Ringu: Kanzen-Ban] which turned out to be very successful so much so that it was given a limited theatrical run. The remake that we know as the “original Japanese version” actually came from that 1995 movie. Stylistically, Hideo Nakata and the other people working on that film were very consciously drawing on what Norio Tsuruta had done back in 1990 with a series of straight-to-video films released here as SCARY TRUE STORIES. These were three very low budget, shot on video things that belonged to a tradition that had been going on for many decades of true life ghost stories. This was a tradition in television and low budget video as well as in book form. It was a market for true life encounters with ghosts. Norio Tsuruta had grown up in a family whose parents owned a movie theater and this was in the 1970s when the Japanese film industry was crumbling. A lot of filmmakers would stay over at his parents’ house because they couldn’t even afford a place to sleep or afford food. So he was surrounded by these images that you cannot support yourself making movies but he loved them and he loved horror movies specifically. He wanted to be a horror director. His family really wanted him to go to business school. He ends up as a marketing executive at a video company during the video boom of the 1980s and he sees that there is a potential to make a low budget horror film and have it be successful.

Many of the familiar tropes of J-Horror first appeared in Norio Tsuruta`s SCARY TRUE STORIES. © 1990 Japan Home Video. US DVD cover art © 2005 Dark Sky Films

Many of the familiar tropes of J-Horror first appeared in Norio Tsuruta`s SCARY TRUE STORIES. © 1990 Japan Home Video. US DVD cover art © 2005 Dark Sky FilmsNow this was a point right after there was a terrible serial killer [Tsutomu Miyazaki] in Japan in 1988 who had slaughtered a bunch of young girls. When they eventually caught him, they found that his apartment was littered with horror videos specifically the GUINEA PIG films and that kind of stuff. So there was a big public outcry that these films were damaging to one’s mental health and they could trigger violence. It was a strong, anti-gore trend. So Norio Tsuruta thinks that this is the opportunity to make horror films without the gore, without the special effects by just focusing on suspense and atmosphere…“We’ll take various urban legends about peoples encounters with ghosts and do it very inexpensively and very simply on video.” It was a huge success and, if you watch SCARY TRUE STORIES, pretty much all of the major imagery that we now associate with J-Horror is in there and sometimes in direct quotes. There’s a scene in Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s PULSE directly copied from SCARY TRUE STORIES. There’re scenes in RING directly copied from SCARY TRUE STORIES. Pretty much all the imagery created by the other filmmakers is right there in that 1990 film. JD: As far as J-Horror directors go, who do you feel has the most talent in the group?

DK: I have two favorites actually. My personal favorite would be Kiyoshi Kurosawa who I think is an extraordinary visionary filmmaker who has reinvented himself time and time again. I think his appeal in terms of mainstream audiences is limited both in Japan and in the U.S. He tends to go more towards the art house kind of crowd. He wins festivals and can be very influential but he’s not going to be a big crowd pleaser. Takashi Shimizu, however, is the crowd pleaser. He has a wicked sense of humor. He is a very self-deprecating man. He has the ability to churn out movies quickly but he’s got razor sharp instincts about what works and what works well with others and I think that he is definitely one that is still on the rise. We’ve not seen the end of him yet. JD: Do you think that J-Horror has burned out in Japan? DK: Not at all. That story is being pedaled here because of the disappointing performance of films like DARK WATER and PULSE. That is not the case there, however. The movies are still continuing to pour out and in fact when I finished this manuscript there were still dozens of movies that were coming out that I wasn’t able to cover that continue to be interesting and innovative. You have to bear in mind that the United States tends to get kind of myopic about our popular culture. We’re such a big nation and what we sell tends to be successful abroad but that doesn’t mean that what’s popular here is the only stuff that is popular elsewhere. If you add up the populations of the countries that have made these films like Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, you come within a few percentage points of the population of the United States. The movies that are made there are less expensive than the ones being made here. A low budget movie by Hollywood standards might be twenty million dollars, forty million dollars. Most of the movies being made in Japan and South Korea in this style, the most expensive of them are probably topping out around like two million dollars. They might be half that or a quarter of that. Now when you add in the much larger potential population of the rest of Asia, countries like China, India, all the Asian nations you’re dealing with a population that is ten times that of the United States. So if you are making films at a tenth of what it costs to make them here for an audience size that is ten times what we have here the risk is very small. You don’t have to appeal to everybody to make extremely profitable horror films of this style in Japan. It is very much still going and Taka Ichise is at the top of all the major franchises and is still making new ones.

The dead menace VERONICA MARS star Kristen Bell in PULSE, the US remake of Kiyoshi Kurosawa`s 2001 J-Horror hit. The American version was a critical and box office failure last year. © 2006 The Weinstein Company

The dead menace VERONICA MARS star Kristen Bell in PULSE, the US remake of Kiyoshi Kurosawa`s 2001 J-Horror hit. The American version was a critical and box office failure last year. © 2006 The Weinstein CompanyJD: Do you think with a movie like PULSE bombing in the U.S. that the trend is over here? DK: I think it is definitely going to be harder to sell those remake prospects now that were in the works over the last couple of years and have gone back into development as the studios have seen that maybe the American audiences have begun to fizzle. But what’s happening is that you are starting to see this imagery pop up in a lot of American productions that aren’t necessarily remakes so J-Horror is taking its root here and it’s going to have its own sort of unique American flavor. It won’t necessarily be a cycle of remakes but it will have an influence.

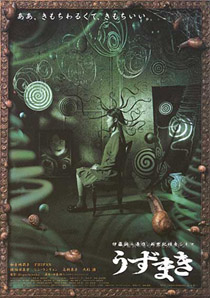

Higuchinsky`s UZUMAKI is one of the most bizarre --yet effective-- Japanese horror films. © 2000 Uzumaki Seisaku

Higuchinsky`s UZUMAKI is one of the most bizarre --yet effective-- Japanese horror films. © 2000 Uzumaki SeisakuJD: When you speak of elements of J-Horror leaking into American productions, are they any specific examples that you have in mind as far as movies go lately? DK: Well unfortunately I don’t get to the movies very often lately. I stay home with my two kids so most of the time when I get to the theater it’s to movies that are appropriate for them to see and horror films don’t always necessarily fall into that category. That’s part of what drew me into this in the first place. Koji Suzuki, who is the author of the original Ring novel, himself is a stay-at-home father and wrote the book while he was taking care of his two daughters, and his wife was the bread winner of the family. That is really especially rare in Japan so much so that he became a parenting advocate. His first couple books were about parenting and he would lecture in front of the Japanese Diet about changes with the laws of society that he felt were necessary to enforce fatherhood as a serious thing for men to aspire to in Japan. This is really one of the themes that comes through, not just in the stuff that was derived from his work but so many other J-Horror films. They’re about issues of parenting and about very real social concerns. I think the most popular horror films in America right now are very violent and, you know, like the Eli Roth trend… JD: Like HOSTEL? DK: Right. Movies about torture and people want to sit there and be shocked by it. The ones that are coming out of Asia, Japan and South Korea especially are films that are about very contemporary social issues. JD: What are your favorite J-Horror films and why? DK: PULSE is definitely at the top of my list and that is why it was so disappointing to see such a lackluster Americanization of it. But maybe if people see and hear about the remake that will inspire them to go back and find the original, and it certainly got the original a long overdue DVD release here. That film is definitely one of the scariest things I’ve ever seen.

There’s also a really fun one that Masayuki Ochiai did. He got his start with PARASITE EVE and continued on in that cycle of hospital themed medical horrors. He did one for the J-HORROR THEATER cycle recently called INFECTION which in some ways riffs on classic Toho science fiction films like THE H-MAN. Those are some of the references he brings into it. It’s like ER meets The H-MAN. That one is a lot of fun and was actually discussed for an American remake. Again, I hope that instead people just go see the original. JD: Where do you see J-Horror going in the near future? DK: I think it is going to continue to be a successful run of modest, small scale thrillers made in Japan and South Korea primarily for their domestic audience. The commercial pressures there discourage a lot of experimentation. The times the filmmakers tried to stretch the boundaries of it and bring in new imagery or new kinds of approaches to it they tend to not do as well at the box office in those countries. It’s kind of a catch-22 situation from an American standpoint because audiences and critics here will look at them and say that they are very derivative and they all look like THE RING and why can’t they do anything differently. But that is exactly what the audiences there want. That doesn’t mean that they aren’t very well made. I just saw something called NOROI: THE CURSE that was produced by Taka Ichise. It’s kind of like the Japanese version of THE BLAIR WITCH PROJECT; very inexpensive but extremely successful for its aims. It’s a small film but it works on its terms and I think that’s the kind of thing that we’re going to continue to see for at least another decade to come. JD: Well David, thanks for doing the interview and for talking about J-Horror. DK: My pleasure!