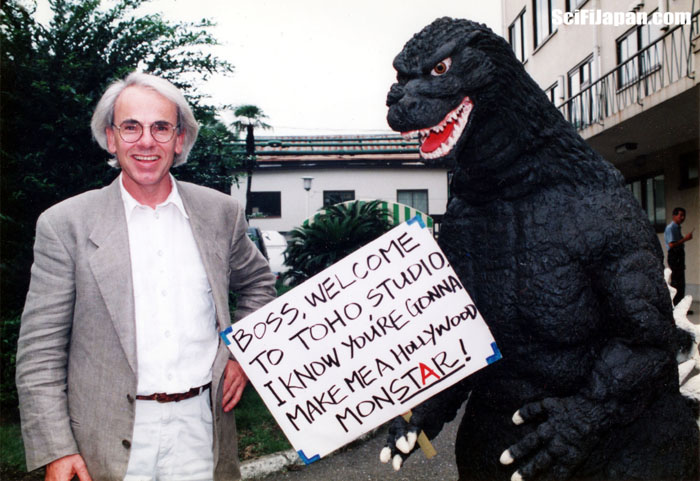

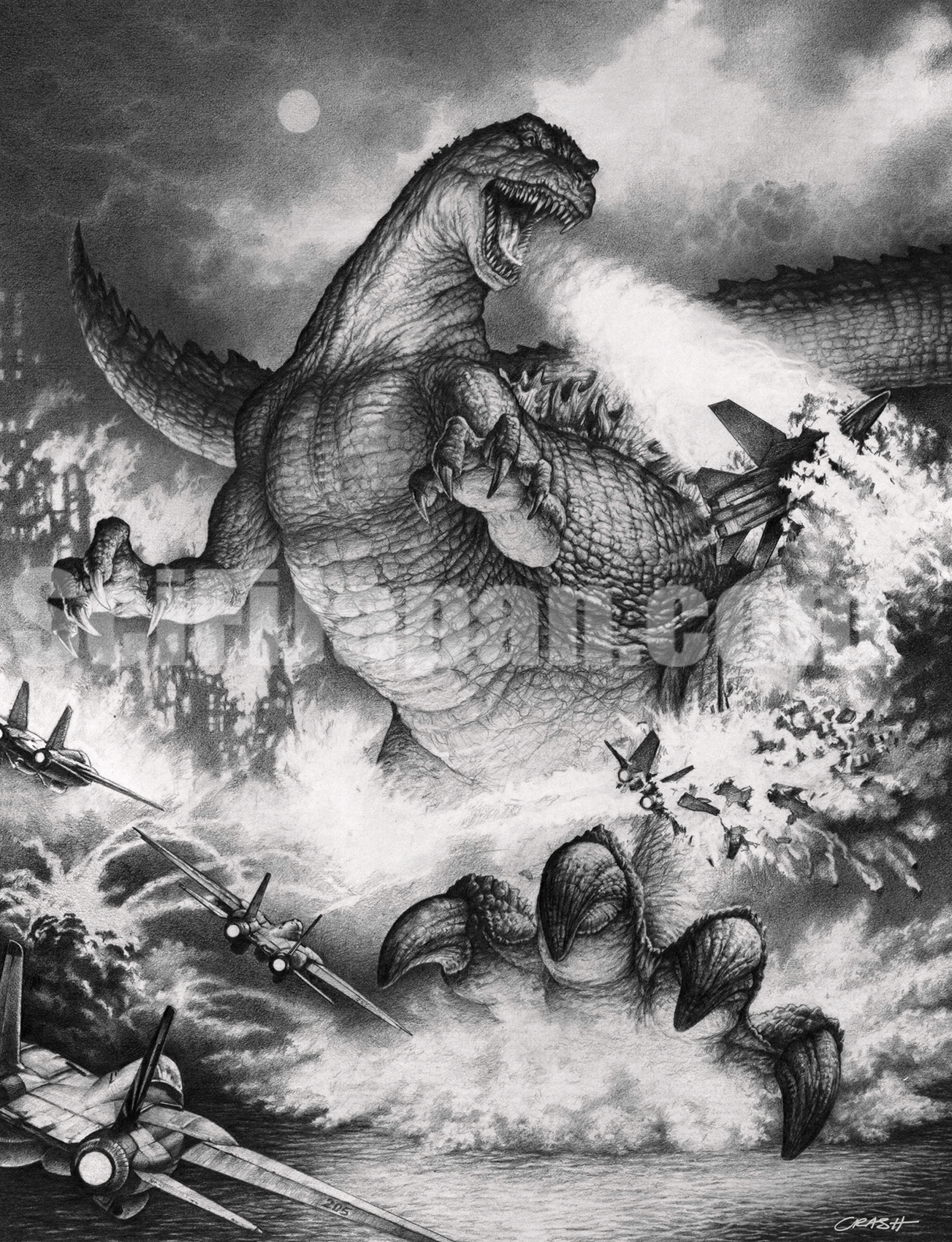

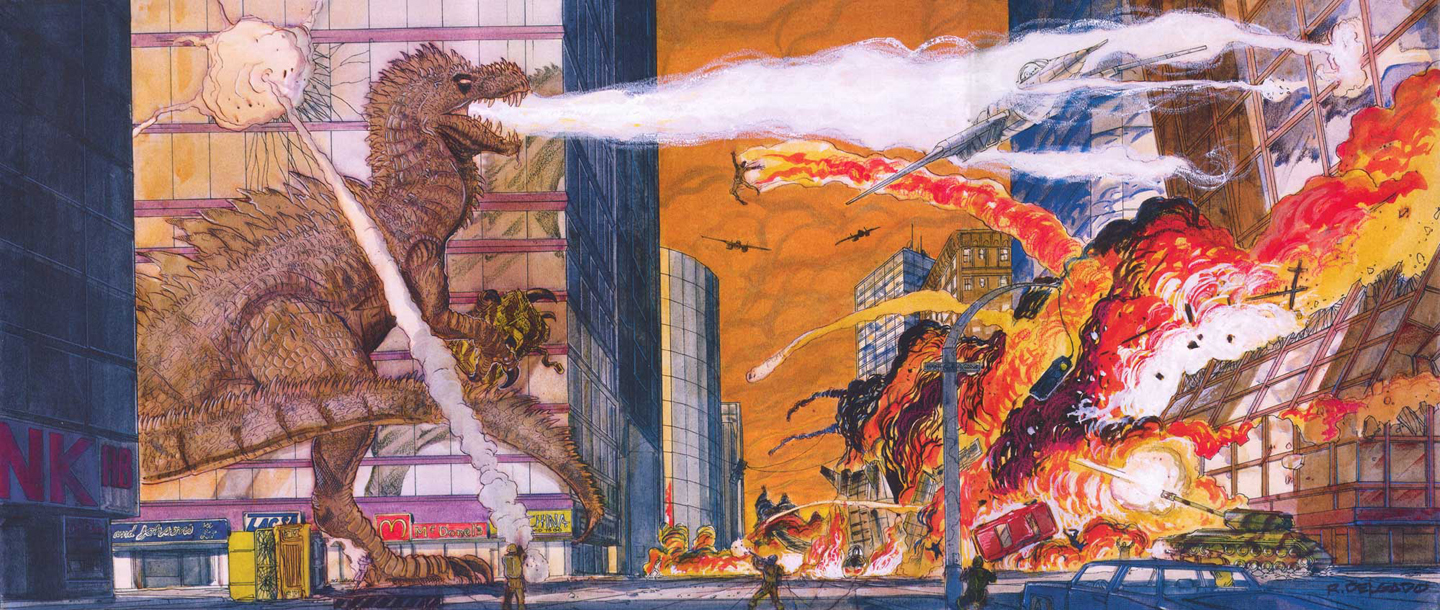

A selection of pre-production art and sculpts from various stages of TriStar Pictures` initial, unrealized version of their American GODZILLA movie. © 1993-1995 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.

A selection of pre-production art and sculpts from various stages of TriStar Pictures` initial, unrealized version of their American GODZILLA movie. © 1993-1995 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.Interviews, Never-Before-Seen Photos, Storyboards, and Production Art from Sony Pictures` Abandoned First Attempt

Author: Keith Aiken

Special Thanks to: Please See ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Below

A SCIFI JAPAN EXCLUSIVE

IMAX poster for the 2014 GODZILLA. Image courtesy of Warner Bros. Pictures. © 2014 LEGENDARY PICTURES PRODUCTIONS LLC & WARNER BROS ENTERTAINMENT INC. GODZILLA TM & © Toho Co., Ltd.

IMAX poster for the 2014 GODZILLA. Image courtesy of Warner Bros. Pictures. © 2014 LEGENDARY PICTURES PRODUCTIONS LLC & WARNER BROS ENTERTAINMENT INC. GODZILLA TM & © Toho Co., Ltd.On May 16, 2014, Warner Bros. Pictures released GODZILLA, a $160 million American adaptation of the long-running Toho Co. franchise. Co-produced by Legendary Pictures and directed by Gareth Edwards, the film finally gave many fans what they had long hoped to see... a big-budget, Hollywood take on the King of the Monsters with state-of-the-art visual effects. Well-received by critics and audiences, the new GODZILLA was a box office success, with a sequel announced for 2018.

The generally positive reviews for the 2014 film were a sharp contrast to the reception given the first Godzilla movie made by an American studio. In October 1992, TriStar Pictures (a subsidiary of Sony Pictures Entertainment) announced that they had signed a deal with Toho to produce an American Godzilla film with “A-list stars, screenwriter, and director” which could potentially launch a series of sequels.

On May 19th, 1998 -- five and a half years after that announcement -- TriStar`s GODZILLA finally opened on a record-breaking 7,363 theater screens across the United States. Co-written by director Roland Emmerich and producer Dean Devlin, the team behind the blockbuster INDEPENDENCE DAY (1996), produced for a reported $130 million and backed by a year-long, $50 million domestic advertising campaign, GODZILLA was widely expected to break box office records on its way to becoming the top grossing film of the year. But moviegoers were unimpressed by the filmmakers` interpretation of Godzilla, which strayed far from the look and character of the near-indestructible, city smashing monster seen in the Toho movies.

TriStar`s GODZILLA finished its US theatrical run at $136 million, with foreign box office bringing the worldwide total to $374 million... a respectable sum, though far less than industry analysts or (more importantly) Sony Pictures had anticipated. While not the financial bomb it is often reported to be, the film failed to deliver what audiences, exhibitors, licensees or the studio wanted and effectively killed the franchise at Sony. TriStar initially considered moving forward with a GODZILLA 2, but eventually abandoned those plans and let their Godzilla film rights revert back to Toho in 2003, allowing Warner Bros. and Legendary to make a new deal with Toho in 2010.

Theatrical poster for the American GODZILLA movie released by TriStar in 1998. © 1998 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.

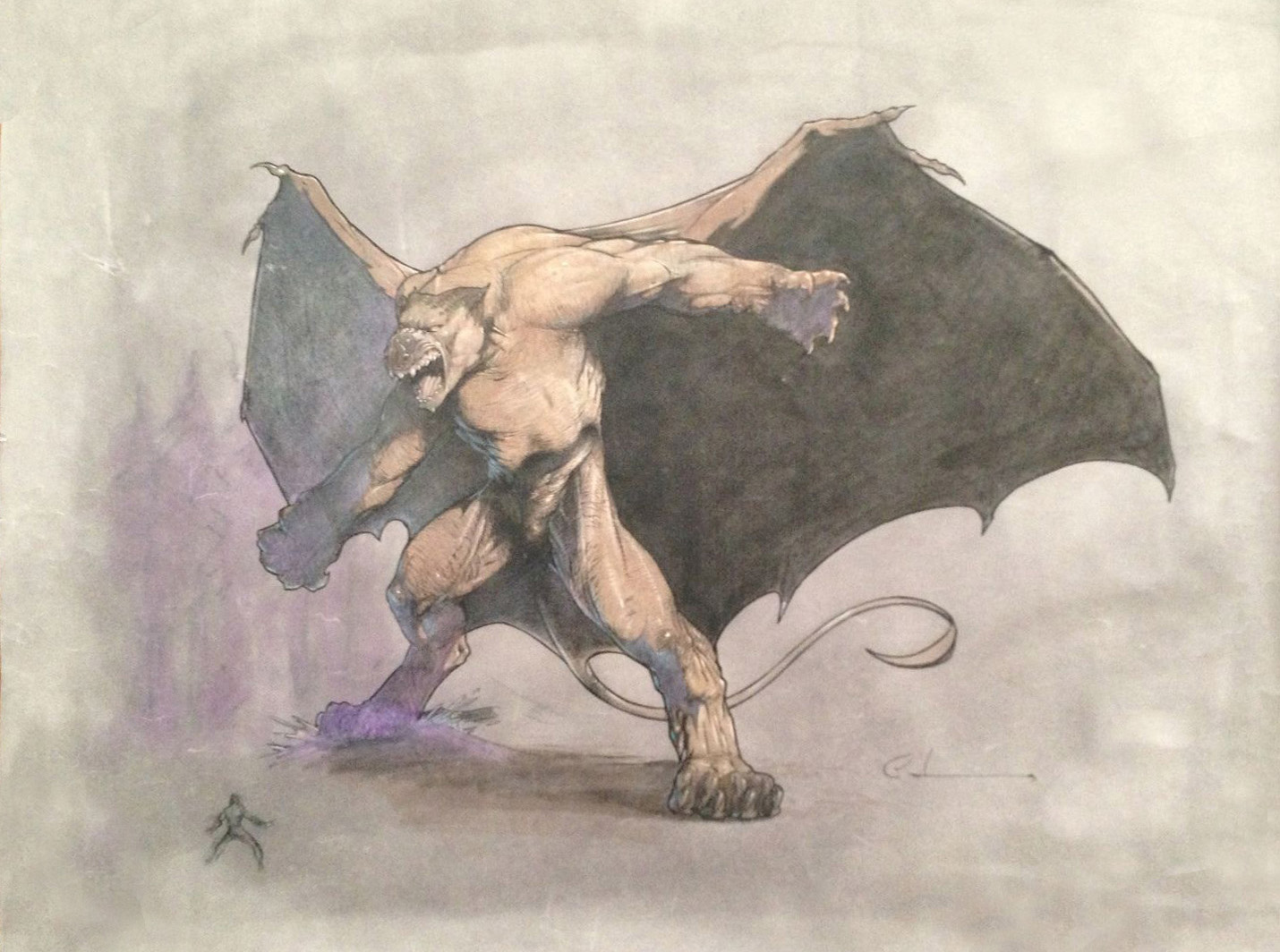

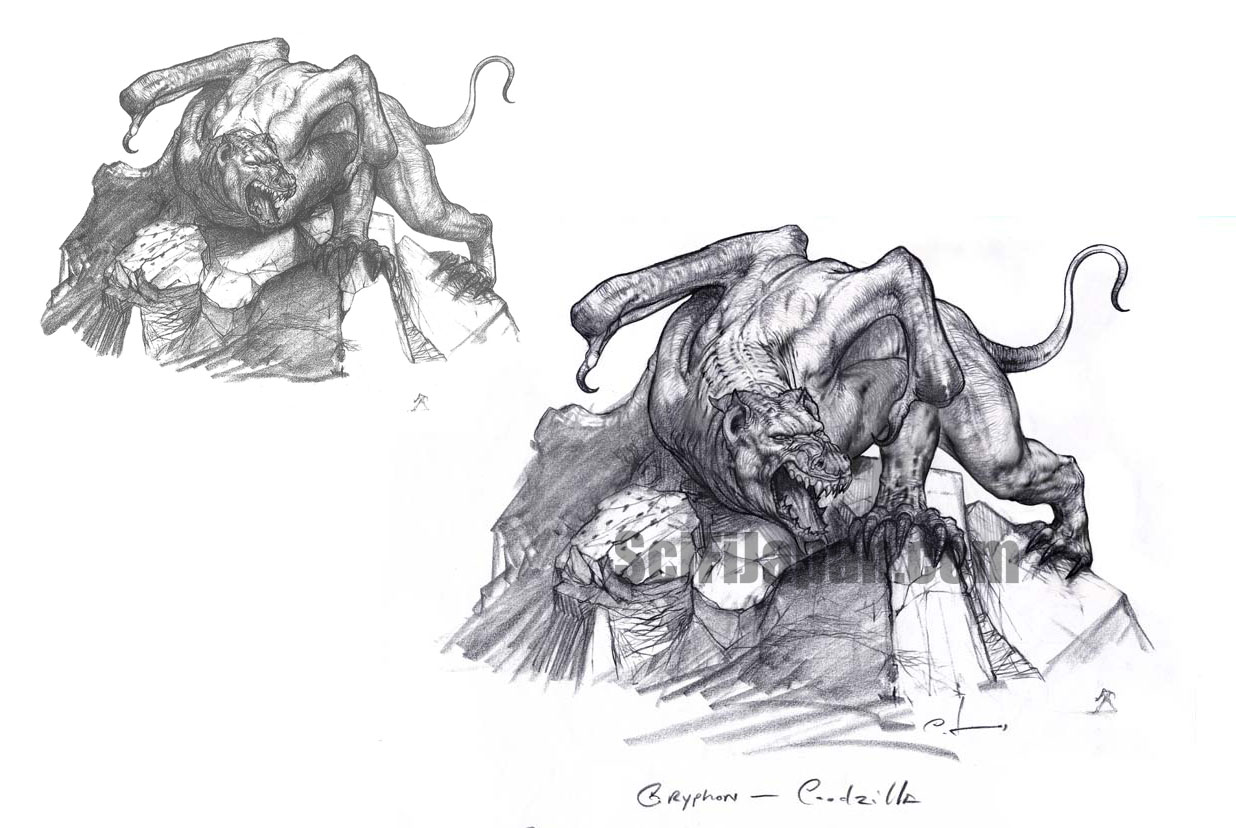

Theatrical poster for the American GODZILLA movie released by TriStar in 1998. © 1998 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.But, as many Godzilla fans are well aware, Devlin and Emmerich`s GODZILLA was actually the result of TriStar`s second serious attempt to produce a Godzilla film... and the first version -- while taking some liberties -- would likely have resulted in a Godzilla much closer to the classic Toho character, nearly two decades before the Gareth Edwards movie. In July of 1994 the studio had signed director Jan De Bont (SPEED, TWISTER) to film a Godzilla story by screenwriters Ted Elliott and Terry Rossio (the PIRATES OF THE CARIBBEAN series). Character designs for an updated Godzilla, a new opponent called the Gryphon, and additional creatures were sketched and sculpted; storyboards were drawn; designs for sets and locations were created; a production team was assembled; casting choices were discussed; construction started on the first set... and then everything fell apart when TriStar canceled the project, supposedly over a budget dispute with De Bont.

Between 1992 and 1995, the announcement, evolution, and sudden death of Jan De Bont`s GODZILLA were covered in a handful of short articles and news bites in film industry trades, entertainment magazines, sci-fi publications and fanzines. As more information and images were gradually revealed in bits and pieces over the years, many Godzilla fans came to view De Bont`s GODZILLA as a major lost opportunity; a missed "once in a lifetime" chance to see a beloved icon brought to cinematic life with the latest in FX technology. While the 2014 GODZILLA may have softened that blow for many fans, there is still strong interest and many questions about the American GODZILLA that almost came to be.

SciFi Japan is pleased to offer a look back with some never-before-seen gems detailing the origins of the TriStar GODZILLA, the surprising amount of work done for the Jan De Bont version, the first attempt to revive GODZILLA after De Bont`s departure, and how the project eventually evolved into the Roland Emmerich film.

- FACE TO FACE WITH THE MISSING LINKS

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- ORIGINS

- DEVELOPING THE STORY

- THE SCREENPLAY

- DIRECTOR HUNT

- THE FIRST FX TEST

- JAN De BONT

- PRE-PRODUCTION BEGINS

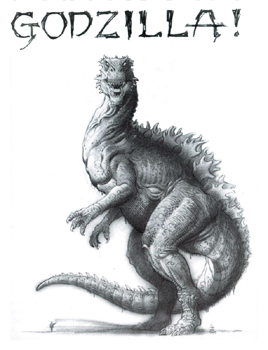

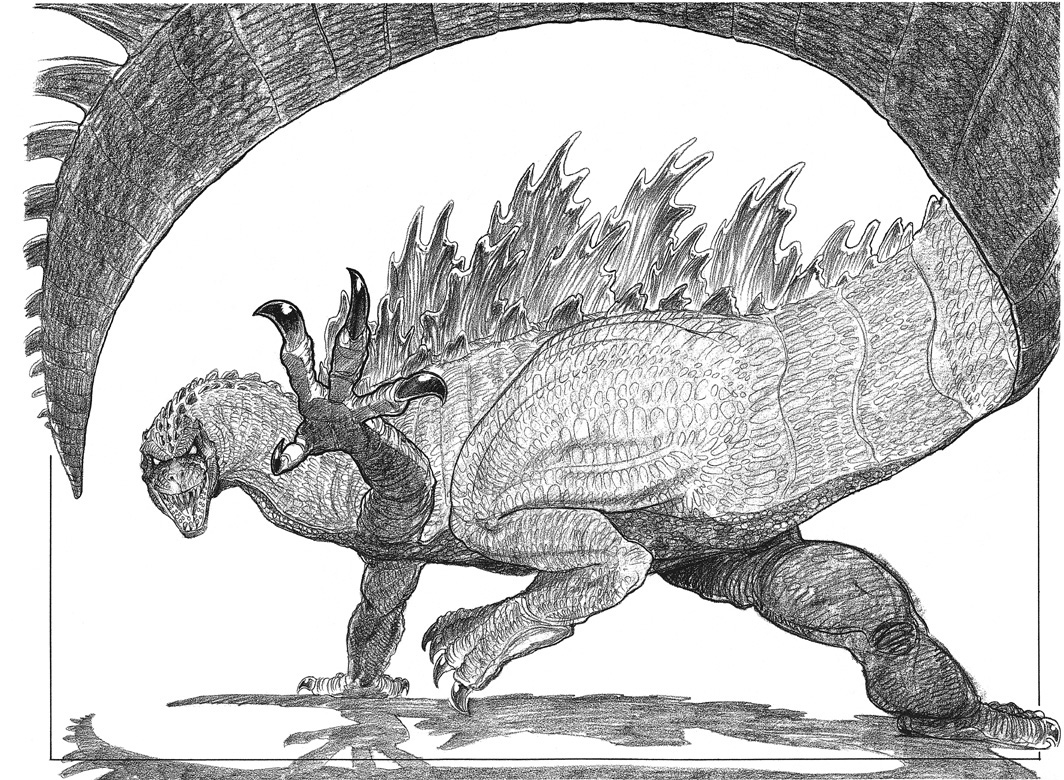

- CONCEPTUAL DESIGN, ROUND ONE: GOJIRA PRODUCTIONS and STAN WINSTON

- STORYBOARDS

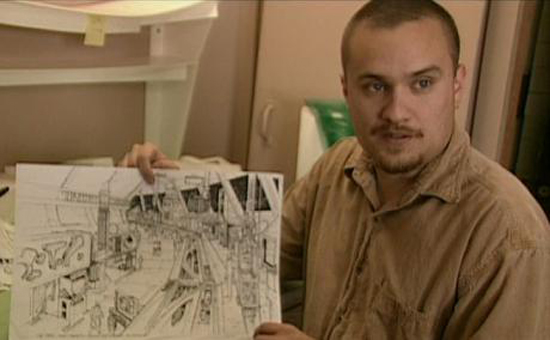

- DIGITAL EFFECTS

- CONCEPTUAL DESIGN, ROUND TWO: WINSTON STUDIO

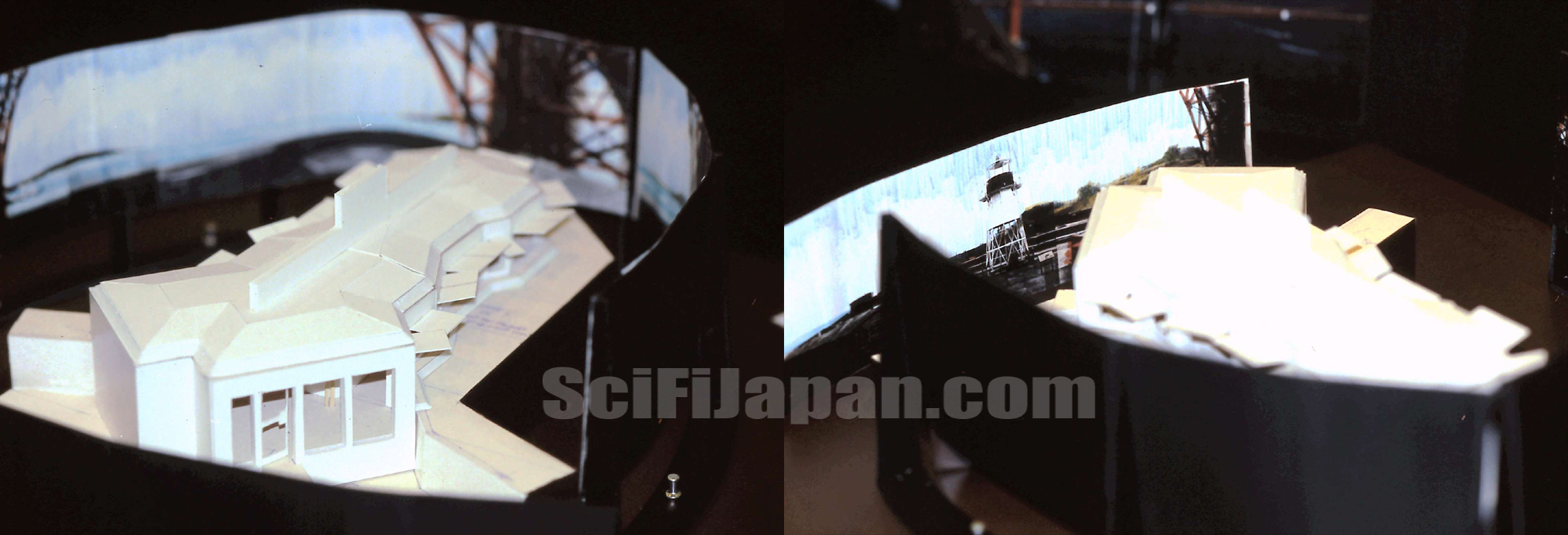

- FINAL PREPARATIONS: CASTING plus MINIATURE and PRACTICAL EFFECTS

- THINGS FALL APART

- RETRENCHMENT

- THE REWRITE

- THE DISCONNECT

- REACTION

- AFTERMATH

- GODZILLA (1994) CREDITS

In 2004, the maquette for the Gryphon (far right) was displayed alongside many recognizable movie models and props in the offices of Winston Studio.

In 2004, the maquette for the Gryphon (far right) was displayed alongside many recognizable movie models and props in the offices of Winston Studio.FACE TO FACE WITH THE MISSING LINKS

2004 marked a half century since the original GODZILLA (ゴジラ, Gojira, 1954) had launched an entire genre of Japanese monster movies. To celebrate that milestone, the American Cinematheque in Los Angeles, CA hosted the "Godzilla 50th Anniversary Tribute" film festival at the Egyptian Theatre in Hollywood from June 24th - 29th, 2004. The event featured screenings of more than a dozen Godzilla and Toho movies, plus appearances by Godzilla filmmakers Masaaki Tezuka (director of GODZILLA AGAINST MECHAGODZILLA and GODZILLA: TOKYO SOS, both premiering at the festival), Yasuyuki Inoue (legendary FX technician with credits going back to the first GODZILLA), and Akinori Takagi (FX artist on the Showa and Heisei Godzilla movies).

Stan Winston (center right) meets with Toho Godzilla filmmakers Akinori Takagi, Yasuyuki Inoue and Masaaki Tezuka at Winston Studio on June 25th, 2004.

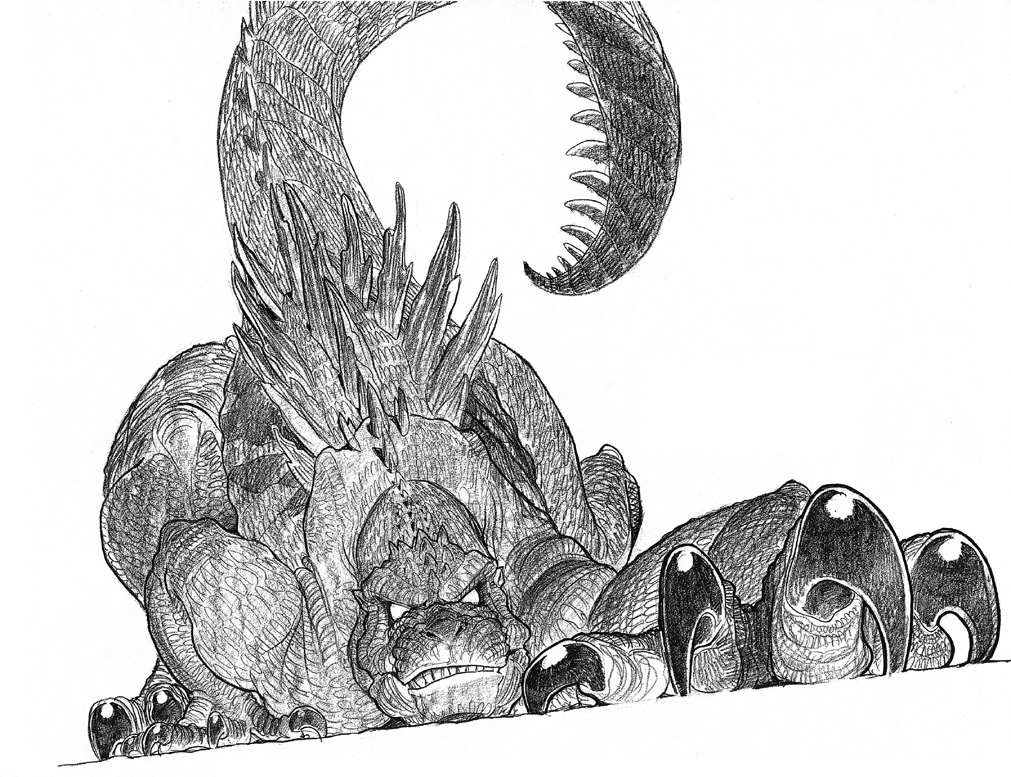

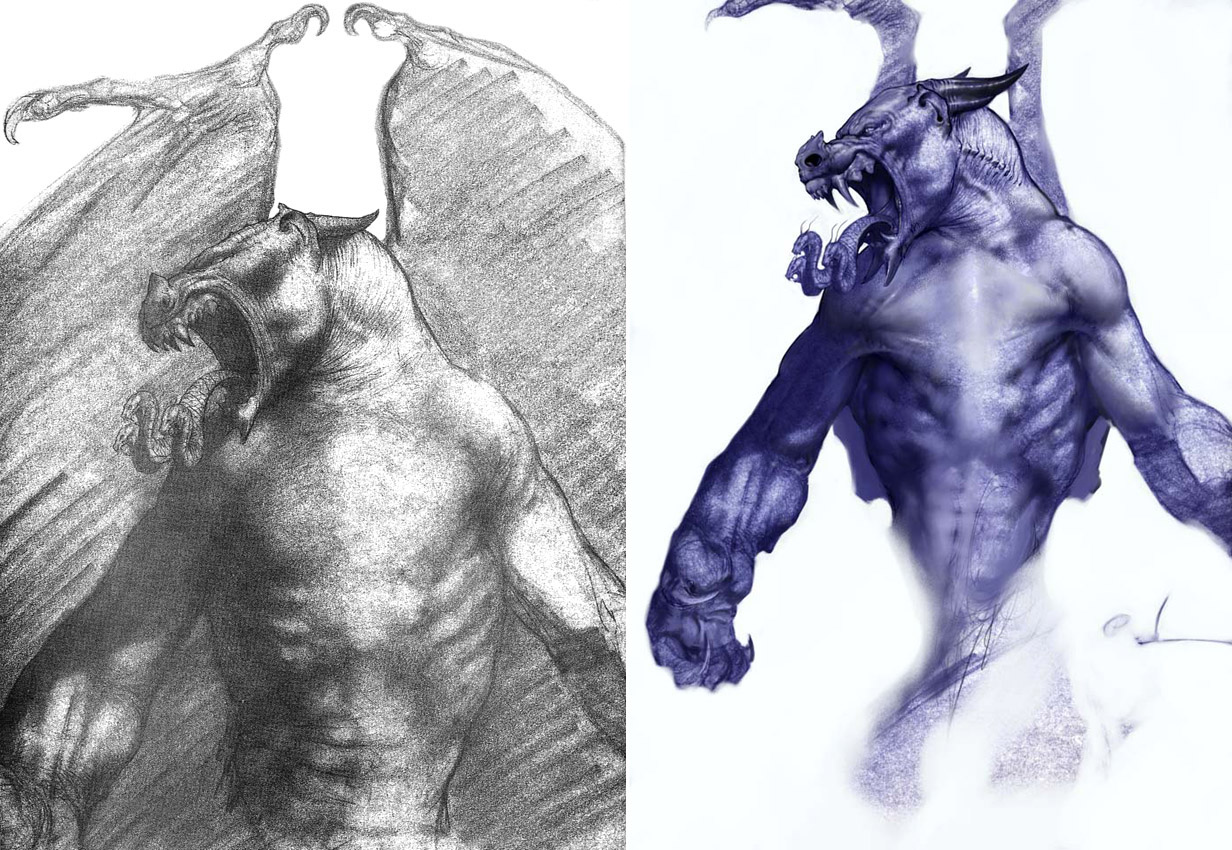

Stan Winston (center right) meets with Toho Godzilla filmmakers Akinori Takagi, Yasuyuki Inoue and Masaaki Tezuka at Winston Studio on June 25th, 2004.As a ‘thank you’ to the Japanese guests attending the festival, the Cinematheque and guest liaison Oki Miyano arranged private tours of several Hollywood FX houses. On June 25th, I was part of a small group invited to visit Stan Winston Studio, the Oscar-winning FX company responsible for some of the most famous creatures, characters, and movie machines in modern cinema. The tour began in the Winston Studio conference room where the visitors met with Mr. Winston and were shown an amazing display of models and props of some of the studio’s top creations. As the group mingled and looked over various life sized Terminators, the Predator, an Alien and Facehugger from ALIENS, the Penguin (BATMAN RETURNS version), Lestat (INTERVIEW WITH THE VAMPIRE), the Kothoga from THE RELIC, Edward Scissorhands, Thermian aliens from GALAXY QUEST, CONGO gorillas, and some JURASSIC PARK Velociraptors, a Spinosaur, and few Tyrannosaurus rexes, we spotted one maquette of a character that never made it to the silver screen... the Gryphon from TriStar`s unmade GODZILLA.

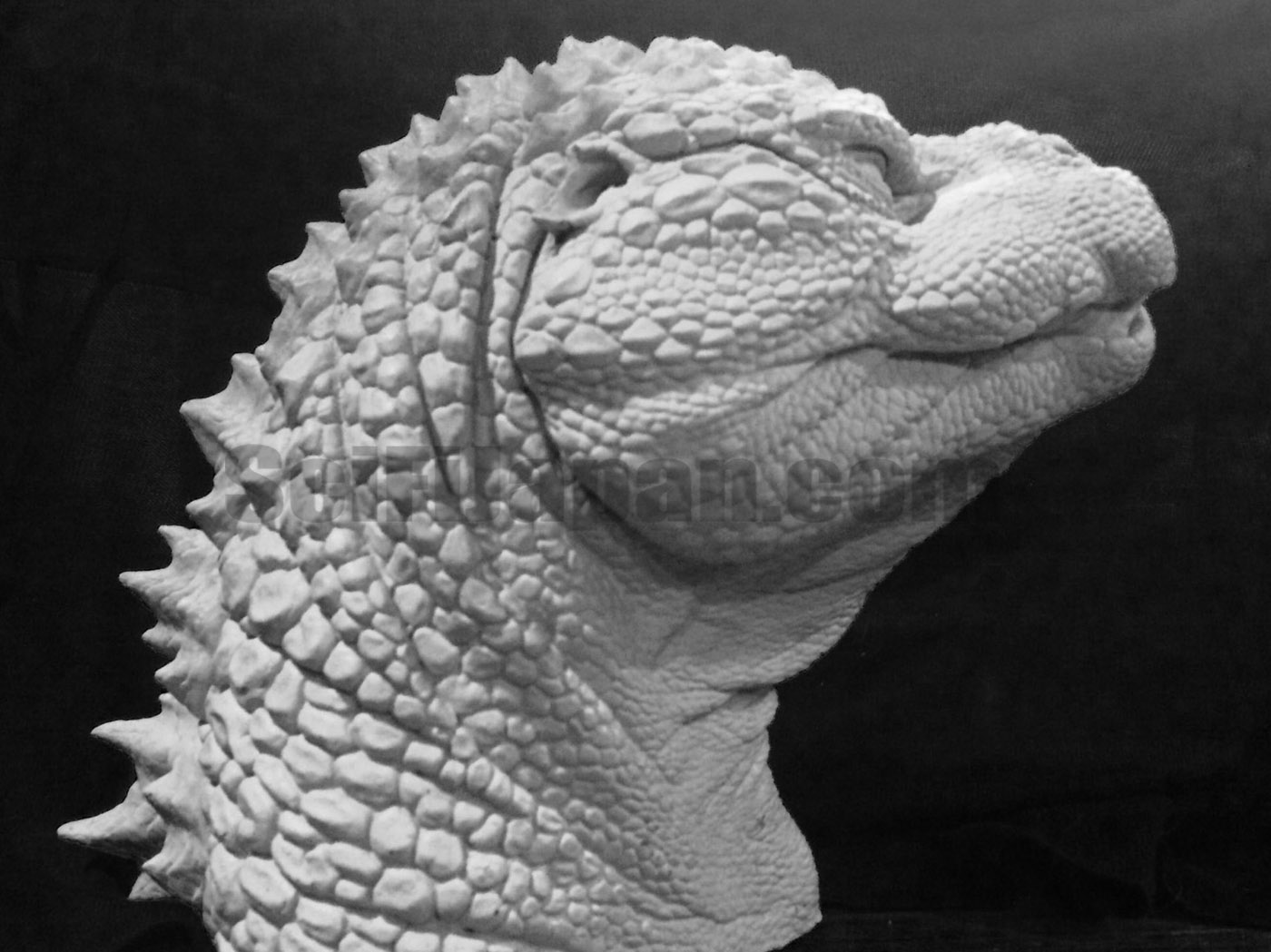

Naturally, a group of Godzilla fans and filmmakers were surprised and excited to see this beast that almost got to co-star with the King of the Monsters. This led to an obvious question, so I asked Winston Vice President Brian Gilbert if the studio still had their Godzilla maquette. They did, and Brian had some members of the staff get the model out of storage for us to see later in the tour. Godzilla was set up in a room where the crew were building suits and props for the then-upcoming Jon Favreau movie ZATHURA (2005) so no photos could be taken, but we were allowed to snap some pics of the Gryphon since that maquette was in a more public area of the studio.

Finally being able to examine both Godzilla and the Gryphon, up close and with my own eyes, so many years after the film had been canceled was a revelation. It also inspired me to research the development of the Jan De Bont GODZILLA for a possible article. I thought that would a simple task; the movie was never made and had only been in active pre-production for about six months so not that much work could have been done. All I would have to do is interview the handful of people involved and track down some pics for a short report.

But I quickly realized that was a foolish assumption on my part. A considerable amount of work went into GODZILLA both before and after Jan De Bont was attached to direct it, which meant many more people were involved than I initially expected. And when De Bont signed on he dove right into the project, hiring a full crew of artists, production designers and FX technicians.

The short article became a long one, and then a multi-part piece as I spoke with dozens of people who had worked on the aborted version of GODZILLA and discovered that much of what had been reported about this project over the years was wrong. I look forward to sharing the filmmakers` own words about what truly went on behind the scenes, along with an array of GODZILLA production art, storyboards and photos, many of which have never been publicly revealed until now.

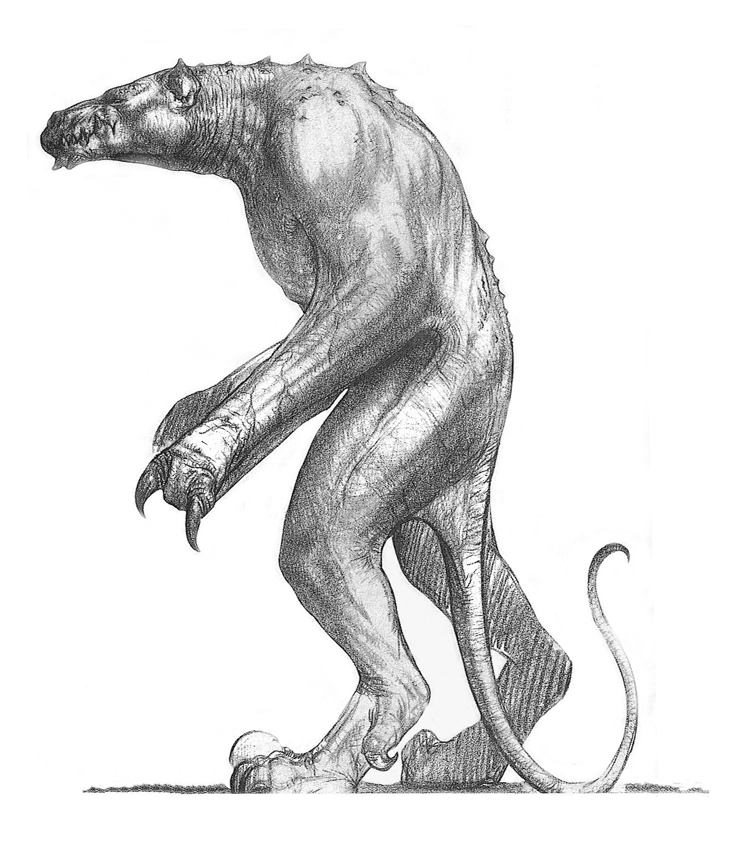

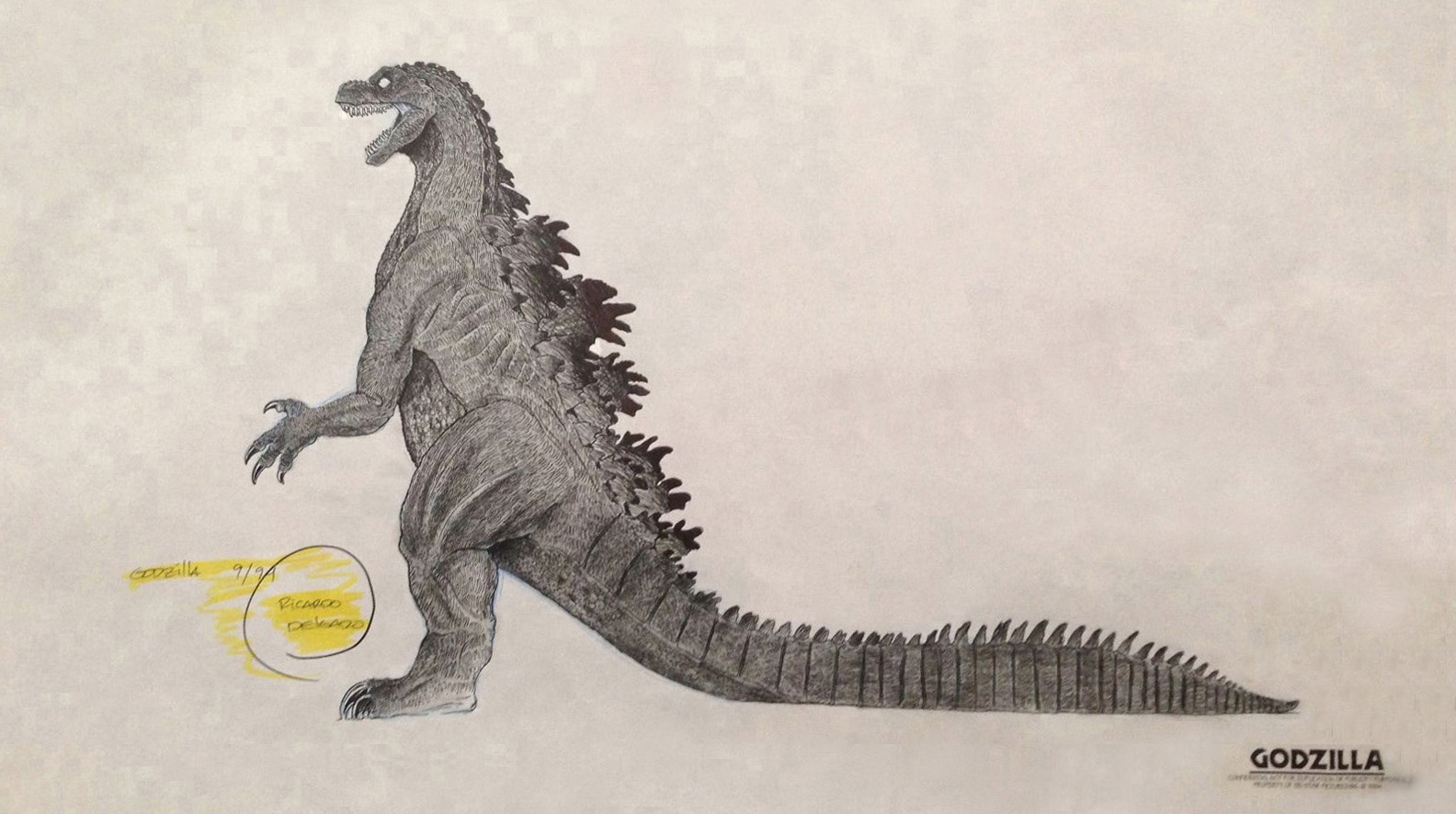

Unfinished maquette of the Godzilla (note the missing claws on his feet) designed by Stan Winston Studio under the direction of Jan De Bont. Photos courtesy of Jan De Bont. © Stan Winston Studio © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.

Unfinished maquette of the Godzilla (note the missing claws on his feet) designed by Stan Winston Studio under the direction of Jan De Bont. Photos courtesy of Jan De Bont. © Stan Winston Studio © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

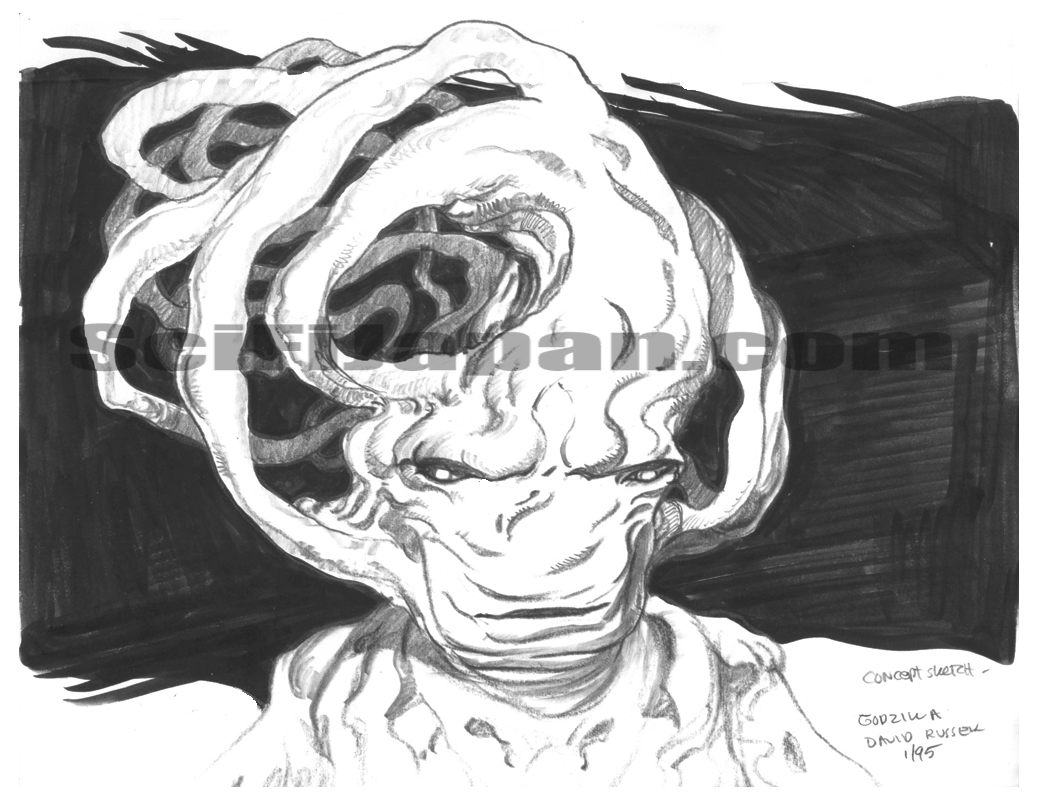

This article would not have been possible without the cooperation of many of the people attached to GODZILLA during its early development, among them director Jan De Bont; Brian Gilbert of Stan Winston Studio; former TriStar President of Production Chris Lee; screenwriters Terry Rossio and Don Macpherson; concept artists Carlos Huante and Ricardo Delgado; storyboard artists David Russell and Giacomo Ghiazza; Winston creature effects artists Mark “Crash” McCreery, Joey Orosco, Paul Mejias, Mark Maitre, Jim Charmatz, David Monzingo, Mike Smithson, Ken Brilliant, Jackie Perreault Gonzales and Bruce Spaulding Fuller; scannable maquette sculptors Jeff Farley, Dirk Von Besser and Chris Bergschneider; mechanical effects supervisor John Frazier; casting director Risa Bramon Garcia; miniature effects supervisor Mark Stetson; digital effects supervisor Richard Hollander; production designer Joseph Nemec III and special effects supervisor Boyd Shermis. All answered questions about GODZILLA, and many provided photos and/or artwork from their time on the film.

Thanks also to Oki Miyano, Dennis Bartok, Gwen Deglise and the American Cinematheque for arranging the Winston Studio tour in 2004; and to Oki and David Chapple for supplying photos taken during our visit to the studio. Matt Winston and Casey Kelly from the Stan Winston School of Character Arts provided GODZILLA photos from the Stan Winston Studio archive, and Matt also set up interviews with some of the Winston artists. Terry Rossio and his assistant, Stacey Collins, sent storyboards from Rossio`s personal collection. Tim Enstice of Digital Domain answered some questions about the project, while Lee Joyner of the Cinema Makeup School helped track down some leads. Fong Sam, general manager of the auction house Profiles in History, offered photos of the Godzilla maquette taken shortly before the model was sold. Jim Ballard, Justin Aclin, Jilly Wendell and Jonathan Shyman gave photo assists. Michael Schlesinger provided some details on Sony Pictures` Godzilla rights. Phil and Sarah Stokes of the Official Clive Barker Website also supplied details from Mr. Barker regarding his early story proposal for GODZILLA. David Kayser at Casarotto Ramsay & Associates helped arrange the interview with Don Macpherson, while Wild Plum owner Shelby Sexton did the same with Jan De Bont. Steve Ryfle originally covered the development of TriStar`s GODZILLA for various magazines back in 1994-95 followed by an expanded overview in his highly-recommended book, Japan`s Favorite Mon-Star (1998). Steve graciously shared his research for this article, including quotes from his interviews with Henry Saperstein, Ted Elliott, Terry Rossio, and producer Cary Woods, as well as a plot synopsis of the first draft GODZILLA screenplay. Richard Pusateri was instrumental in preparing the GODZILLA materials Jan De Bont shared from his personal collection. Comic book artist Todd Tennant (American Kaiju, It Came From Beneath the Sea... Again) provided information and leads. A longtime enthusiast for this unmade film, Todd is currently collaborating with Terry Rossio on an American Godzilla `94 online graphic novel based on the Elliott and Rossio GODZILLA screenplay. Anyone interested in a visual representation of the story should definitely give it a look. Additional information was culled from numerous publications. Please see the footnotes for a complete listing.

Industry trade ad announcing TriStar`s GODZILLA for 1994. Image courtesy of Jan De Bont. © 1993 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.

Industry trade ad announcing TriStar`s GODZILLA for 1994. Image courtesy of Jan De Bont. © 1993 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.ORIGINS

"For ten years I pressured Toho to make one in America. Finally they agreed." --Henry Saperstein

“He was like, ‘Godzilla, the fire-breathing monster?! Yesss!`” --GODZILLA (1994) producer Cary Woods

According to producer Cary Woods, the credit for getting an American version of GODZILLA off the ground belonged to Henry G. Saperstein, the head of United Productions of America (UPA). Woods recalled that Saperstein "had been contacting all the major studios in town, trying to put a deal together for some time."1

Henry Saperstein`s long history with Godzilla and Toho Co., Ltd. began in the early 1960s. A decade before, he got into film and television distribution by providing syndicated programming to the independent TV stations popping up all over the United States. Saperstein`s initial offerings were mostly westerns and other low-budget movies, but he soon began developing his own educational and sports shows. Looking to produce cartoons for television, in 1959 he bought UPA, the Academy Award-winning animation studio behind MR. MAGOO and GERALD McBOING BOING. Saperstein also continued to acquire films for distribution to television through UPA, and looked into making his own movies for theatrical release. “I am known in this business for my nose. I am known to smell when the time is ripe for a deal, for a trend in entertainment, for a development with dollar potentials,” he told Variety in 1963.

Saperstein`s involvement with Toho and Godzilla dated back to the 1964 movie MOTHRA VS GODZILLA, first released in the US as GODZILLA VS THE THING. © 1964 Toho Co., Ltd.

Saperstein`s involvement with Toho and Godzilla dated back to the 1964 movie MOTHRA VS GODZILLA, first released in the US as GODZILLA VS THE THING. © 1964 Toho Co., Ltd.After receiving requests for more science fiction programming, Saperstein contacted Toho in early 1964 and acquired the US theatrical and television rights to the studio`s next Godzilla movie, MOTHRA VS GODZILLA (モスラ対ゴジラ, Mosura Tai Gojira). Both parties soon agreed to a multi-film co-production deal in which Saperstein would invest production money, supply story ideas, and occasionally provide American actors for upcoming Toho movies in exchange for distribution rights in North America. This partnership resulted in such fan favorite daikaiju films as MONSTER ZERO (怪獣大戦争, Kaijū Daisenso, 1965) and FRANKENSTEIN CONQUERS THE WORLD (フランケンシュタイン対地底怪獣, Furankenshutain Tai Chitei Kaijū Baragon, 1965) which both starred Nick Adams (REBEL WITHOUT A CAUSE, THE REBEL), and WAR OF THE GARGANTUAS (フランケンシュタインの怪獣 サンダ対ガイラ, Furankenshutain no Kaijū: Sanda tai Gaira, 1966) with Russ Tamblyn (WEST SIDE STORY, THE HAUNTING).

In the 1970s, Saperstein also began acting as Godzilla`s "agent" in the United States, setting up merchandising and licensing deals for the character with a wide range of companies. He continued in this role into the mid-1990s, licensing Godzilla for the Marvel comic book series, Mattel`s Shogun Warriors toy line, a Hanna-Barbera cartoon show, a product line from Imperial that included a six foot tall inflatable Godzilla, home video releases of the Godzilla films, the Trendmasters toy line, advertising campaigns with Dr Pepper and Nike, and more.

But Henry Saperstein’s greatest Godzilla-related dream was to turn the Japanese monster into a Hollywood movie franchise, asserting, "For ten years I pressured Toho to make one in America. Finally they agreed."2 With Toho`s blessing, Saperstein began pitching Godzilla to the major American film studios and production companies.

He eventually met with two young producers, Cary Woods and Robert N. Fried, who had a production deal with Sony Pictures Entertainment. Cary Woods had started out as an agent at the William Morris Agency, representing the likes of Uma Thurman, Sam Kinison, Tim Robbins, Matt Dillon, and Gus Van Sant, and helping develop indie films such as HEATHERS (1989) before joining Sony Pictures as a vice-president for studio head Peter Guber.

Guber quickly realized that his VP was champing at the bit to produce his own movies, so he paired Woods with Robert Fried -- a former Orion Pictures executive and a recent Oscar winner for the short film SESSION MAN (1991) -- to develop films for the company`s Columbia and TriStar divisions. Their early titles for Sony included the Mike Myers comedy SO I MARRIED AN AXE MURDERER (1993) and the sports hit RUDY (1993). Independently, Woods also produced the controversial KIDS (1995), SWINGERS (1996), SCREAM (1996), and COP LAND (1997), while Fried had his own successes with cult favorite THE BOONDOCKS SAINTS (1999) and the box office hit COLLATERAL (2004).

Nike`s GODZILLA VS CHARLES BARKLEY advertising campaign had given Godzilla fresh exposure in America at the time Sony and Toho were negotiating for the US remake rights. © 1992 Nike, Inc.© Toho Co., Ltd.

Nike`s GODZILLA VS CHARLES BARKLEY advertising campaign had given Godzilla fresh exposure in America at the time Sony and Toho were negotiating for the US remake rights. © 1992 Nike, Inc.© Toho Co., Ltd.Cary Woods and Robert Fried had initially met with Henry Saperstein to discuss the possibility of doing a live action feature film version of MR. MAGOO. But as those talks fizzled (MAGOO would eventually be optioned and released by Walt Disney Pictures), Saperstein mentioned that remake rights for Godzilla were also available. The producers immediately recognized Godzilla`s name value -- the older Toho movies had been seen all over the world, and the character was currently starring in Nike`s successful GODZILLA VS CHARLES BARKLEY advertising campaign in the US -- and believed the franchise was perfect for a Hollywood update with state-of-the-art special effects techniques. "Here was one of the great characters of the movie business," Woods declared to Variety editor in chief, Peter Bart. "A character that was beloved even though he wreaked damage and destruction. Godzilla was the James Dean of monsters. He caused trouble wherever he went, but he was misunderstood."3

The pair also felt the subject matter should be treated seriously, with a story that captured the "anti-nuke/war" spirit of the early films. "I think the raw material is there to make Godzilla a very, very serious and engaging sci-fi character," Woods insisted.4 But when Cary Woods and Robert Fried initially presented the idea to Sony Pictures, they learned that studio executives saw Godzilla in a different light. "We pitched the idea to Columbia and they passed outright. Their response was they felt it had the potential for camp", recounted Woods.5

The two producers had no better luck with Columbia`s sister company. “TriStar did originally pass on the project," Fried explained. "The people who were running the studio at that particular time may not have seen commercial potential there, may not have thought that it would make a great film.”6

The only positive response they received came from Chris Lee, a vice president of production at TriStar. Lee had joined the company in 1985 as a freelance script reader, working his way up the ranks as both a story editor and director of creative affairs. Raised in Hawaii, he had grown up watching Godzilla movies at the (now defunct) Toho Theatre in Honolulu. "I saw the original Japanese version there, as well as the subsequent ones, and I always thought that I`d love to see another Godzilla movie," said Lee. "It was a film that I always wanted to do."7 Lee agreed with Fried and Woods` take on the property, telling them, "The creature was not just menacing, he was also mythic."8 He felt that a new GODZILLA should be done "in the spirit of the first movie, which was not campy. I wanted to reflect not what the movie [series] had become but how it started out. I loved the goofier Godzillas too, but I knew a new version was about taking it seriously. You can`t consciously set out to make it campy."9 But despite his faith in GODZILLA as an American production, he did not have the power to green light the movie.

Getting nowhere fast, Woods took a mammoth gamble, going over the execs` heads and taking GODZILLA directly to his former boss, Peter Guber, Chairman of the Board and Chief Executive Officer of Sony Pictures Entertainment. "I was lamenting my futility to my wife, and she asked, `have you pitched Guber?`," he recalled. "I explained that I can`t pitch Guber -- he`s the boss, the head of the company. He doesn`t want to get involved in production decisions. She just stared at me and said, `Pitch Guber`."10

Over his long career, Peter Guber had been involved in a number of critically and commercially successful films such as SHAMPOO (1975), TAXI DRIVER (1976), THE DEEP (1978), CLOSE ENCOUNTERS OF THE THIRD KIND (1978), AN AMERICAN WEREWOLF IN LONDON (1981), RAIN MAN (1988) and BATMAN (1989). But he also had a reputation as a better self-promoter than a producer, and had what at best could be called a "strained" relationship with several top filmmakers, among them Steven Spielberg (who banned Guber from the set of THE COLOR PURPLE) and Tim Burton (who described making BATMAN as "Torture"). In 1989, Guber was hired by the Japanese electronics company Sony Corporation to run Sony Pictures. During his reign at Sony, Guber was seen as being more interested in the general outlook of the company rather than individual productions, and executives and producers would increasingly complain about their difficulties in getting projects approved at the studio.

Cary Woods decided approaching Peter Guber at the office would most likely not work... and would also draw unwanted attention from the studio execs who had already rejected GODZILLA. Instead, he flew from Los Angeles to Florida -- where Guber had a speaking engagement -- and surprised the CEO at the event with a direct pitch. Half-expecting to be reprimanded for breaking protocol, Woods was relieved when Guber began talking about Godzilla as an "international brand" that could support not just one movie, but a series of films for years to come.11 "Peter got it; he saw the movie in his head," Woods reported. "He was like, `Godzilla, the fire-breathing monster?! Yesss!`" 12

Peter Guber set up GODZILLA at TriStar (which had been struggling to match Columbia`s high-level output) and contacted Norio Ohga, Chairman and CEO of Sony Pictures` parent company -- the Japanese electronics giant Sony Corporation -- to discuss the most effective way to license the Godzilla rights from Toho. TriStar Vice Chairman Ken Lemberger was sent to Tokyo to personally oversee the deal, and negotiations with Toho launched in mid-1992. “The timing was pretty good," Robert Fried revealed. "Internally [Toho] were beginning to have discussions that if the right idea came along they would entertain it. And they were happy with the proposal that we made. We said that the time was right to do a big budget American version, a high-end special effects summer release version of the film, and that we would take it seriously and that we would be respectful of the legend. And they appreciated that approach and decided to take it a step at a time.”13

For Toho it was a no-lose situation; Sony Pictures was offering a $300,000-400,000 advance payment plus an annual licensing fee to use the Godzilla character for a large-scale American production with "A-list talent". Toho would also receive production bonuses, be given distribution and merchandising rights to the film in Japan, and a percentage of profits from international ticket sales and merchandising. In addition, Toho could continue to make their own Japanese Godzilla movies -- which had been doing big business back home -- while the TriStar film was in development.

Even so, Fried conceded that the step-by-step negotiations with Toho were "a painstaking process." TriStar wanted to develop an original story, unconnected to any of the other Godzilla films, and the character and appearance of this new take were of great concern to Toho. "They even sent me a four-page, single-spaced memo describing the physical requirements the Godzilla in our film had to have. They`re very protective," he said.14

Toho wanted the design of the American Godzilla to resemble the look of the monster in the recent Japanese films. © 1989 Toho Co., Ltd.

Toho wanted the design of the American Godzilla to resemble the look of the monster in the recent Japanese films. © 1989 Toho Co., Ltd.Toho wanted the new Godzilla to closely resemble the Japanese version, so they prepared a list of "Do`s and Don`ts" for TriStar to follow. The lengthy document -- which was reportedly expanded to more than 75 pages -- set down a series of rules defining the monster`s background (Godzilla must be created by a nuclear accident), behavior (Godzilla does not eat people), appearance (Godzilla must have three rows of dorsal fins, Godzilla has four claws on each hand and foot, Godzilla has a long tail) plus such key stipulations as "Godzilla must not be made fun of" and "Godzilla cannot die". Toho`s Tomoyuki Tanaka, co-creator of Godzilla and producer of the Godzilla film series, affirmed that, "TriStar has promised us they will maintain and preserve the character of Japan`s Godzilla. I`m looking forward to seeing Godzilla created by the American people. We`d like to have Godzilla go out to the world."15

Under the terms of the contract between Toho and Sony Pictures, Toho would grant usage rights to the "character and likeness" of Godzilla for an American movie to be produced, marketed and distributed by TriStar. Sony would own rights to the picture worldwide except for Japan, where Toho would have ownership and handle distribution. The two studios would maintain these rights in perpetuity, guaranteeing that the film -- and the creature created for it -- would forever be copyrighted and trademarked worldwide as “Godzilla”. This key point would later become a major irritation for many Godzilla fans.

In addition, Sony Pictures also acquired merchandising rights outside Japan, would be allowed to produce an animated spin-off show for television (this would eventually result in the Saturday morning cartoon program, GODZILLA: THE SERIES) and was granted usage rights to most of the monsters from the first 15 Godzilla films produced by Toho from 1954-1975. While sequels were not guaranteed in the agreement, the American studio was granted an option for additional Godzilla films which would be handled on a picture-by-picture basis with Toho.

As the creators and owners of Godzilla, Toho would control the character and likeness rights to the American Godzilla. Therefore, Sony would need Toho`s permission to use the new Godzilla in any manner not stipulated in the contract (Toho would later nix a Godzilla cameo in Sony’s animated series BIG GUY AND RUSTY THE BOY ROBOT). On the other hand, Toho would be free to include TriStar`s Godzilla in their own productions once their deal with Sony Pictures had concluded.

TriStar president Mike Medavoy was not pleased with how the GODZILLA deal was initiated by Woods and Guber.

TriStar president Mike Medavoy was not pleased with how the GODZILLA deal was initiated by Woods and Guber.But as the Sony/Toho deal came together in Japan, Cary Woods started feeling the heat back in Los Angeles. His direct appeal to Peter Guber had gotten GODZILLA off the ground, but had also created a lot of anger and resentment among the studio executives he had bypassed along the way. Woods recalled that, "Mike Medavoy, then president of TriStar, phoned me to say, `I don`t want to talk to you. If you feel you can go directly to Guber for decisions, be my guest, but stay off my phone list`." When Peter Guber learned of the conversation, he advised Woods, "Don`t let Medavoy scare you. He may be off the lot before long."16

On October 29, 1992, Variety publicly broke the news that TriStar and Toho had signed a deal for GODZILLA. TriStar announced GODZILLA as part of a slate of big budget, high profile "tentpole" productions they expected to start releasing in 1994... the lineup also included MARY SHELLEY`S FRANKENSTEIN (1994), TAKING LIBERTY (never produced), Terry Gilliam`s CARTOONED (never produced) and James Cameron`s SPIDER-MAN (made without Cameron and released by Columbia in 2002). Mike Medavoy told the magazine that studio executives had been looking for franchise properties, observing, "It is obvious that TriStar has embarked on the strategy of putting its own large pictures into the mix."17 Robert Fried stated that GODZILLA was being fast-tracked for development, with offers going out to writers and directors in the next few months. He added that a best-case scenario would lead to production beginning in late 1993.

In an amusing note, on the exact same day the Variety article ran, the Los Angeles Times published their own report on the TriStar GODZILLA. Medavoy refused to answer reporter Ryan Murphy`s questions, but other sources confirmed that the project "has been in top-secret planning stages for weeks" and was tentatively scheduled for a Christmas 1994 release.18

Both the Variety and Los Angeles Times articles mentioned a rumor -- the first of many -- that had been circulating about GODZILLA. Unaware that the project had begun with Henry Saperstein, Cary Woods and Robert Fried, some supposedly "knowledgeable industry sources" had suggested that GODZILLA (a Japanese property) had been forced on TriStar by their owners at Sony Corp. (a Japanese business). "When Sony took over TriStar and Columbia, the big joke around town was `we`re gonna see a lot of Godzilla and kung fu movies`," one unnamed source told the Times. "But Sony officials were adamant at the time that they would not enforce their taste on the American popular culture. The decision, then, to make a Godzilla movie is priceless. The whole project smells like somebody in Tokyo had an idea."19

TriStar reps quickly denied the claims, insisting, "That`s just ridiculous. There`s been no interference from them at all... That`s a very paranoid disillusion. [Godzilla is] a worldwide phenomenon and a very well-known character. He`s the ultimate monster. Therefore, if this is done well, and it will be, it could be a sensational movie."20 Cary Woods further set the record straight, telling Variety that GODZILLA was "a clear example of the kind of synergy that can exist when American producers and an American studio want to pursue something that is uniquely Japanese. It`s an example where something got done with their help, as opposed to their insistence."21

Another TriStar associate would later maintain that, while the idea to remake GODZILLA originated in America, the head office in Japan recognized the inherent possibilities. "This is exactly the kind of movie that defines why Sony got into this business," he said. "It`s a piece of fluff that can be exploited in every single way: CD-ROMs, ride films, talking books, electronic media, everything. It`s definitely an event film."22

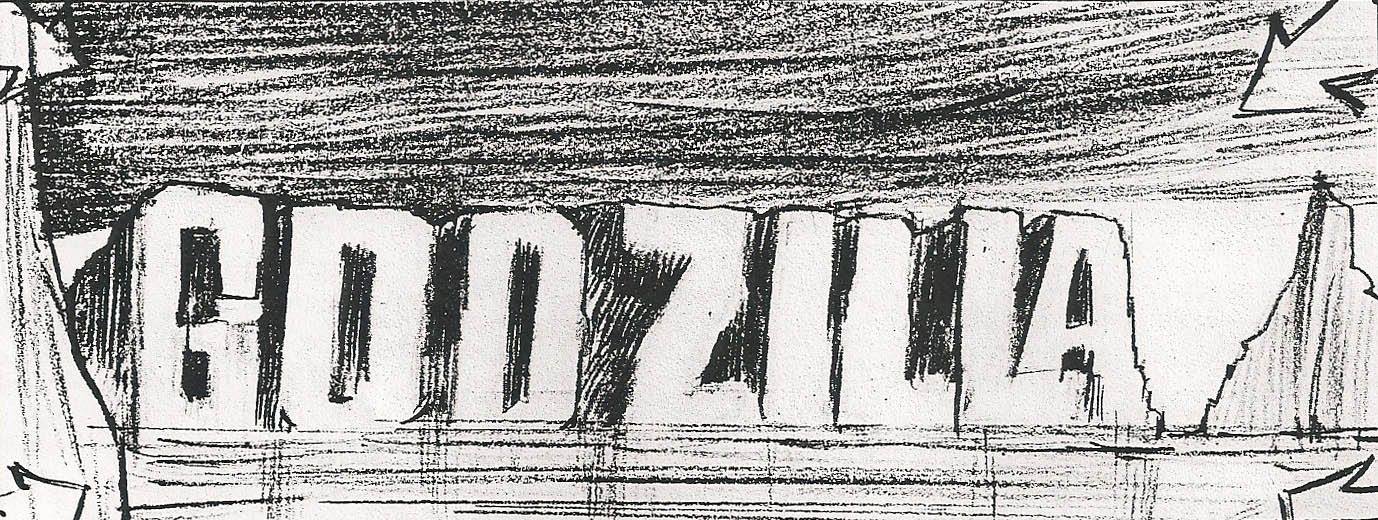

TriStar officially announced GODZILLA in November 1992, with trade ads in industry publications proclaiming a worldwide release for 1994. With Steven Spielberg’s highly anticipated JURASSIC PARK set for May, 1993, TriStar saw GODZILLA as the perfect vehicle to exploit the expected audience demand for similar big budget, high-tech dinosaur/monster movies. The budget for the film was anticipated to be in the $40 million range; roughly four times the amount Toho had recently been spending on their own Godzilla movies in Japan. Toho was thrilled at the prospect. "We`re really eager to see how a Godzilla film made by Americans will turn out," company rep Takashi Nakagawa commented to the Associated Press. "It`s great news for all Godzilla fans."23

Original GODZILLA director Ishiro Honda (shown here with FX director Eiji Tsuburaya) gave his blessing for the new film. © Toho Co., Ltd.

Original GODZILLA director Ishiro Honda (shown here with FX director Eiji Tsuburaya) gave his blessing for the new film. © Toho Co., Ltd.Nakagawa`s enthusiasm was echoed by several people who had worked on Toho`s Godzilla films. "I`m pleased," original Godzilla suit actor Haruo Nakajima told interviewer David Milner. "I hope that a competition will spring up between Toho and TriStar."24 Koichi Kawakita concurred, saying, "I have great expectations. I`m looking forward to seeing it, not only because I direct special effects for Godzilla films but also because I am a movie fan."25

FX director Teruyoshi Nakano (GODZILLA VS HEDORAH, THE RETURN OF GODZILLA) said, "I`m pleased that a new approach will be taken,"26 while director Jun Fukuda (GODZILLA VS THE SEA MONSTER, GODZILLA VS MEGALON) added, "I can`t imagine what Americans would do with it. I think that Godzilla films must be produced by Americans."27 And Ishiro Honda, director of the original GODZILLA and many of Toho`s classic FX films, gave his approval, feeling that, "It will probably be much more interesting than the ones [currently] being produced in Japan."28

But Toho actor Kenji Sahara (RODAN, KING KONG VS GODZILLA) was a bit more hesitant. "I have mixed feelings about it," he admitted. "I am looking forward to seeing the film, but since I take part in the production of Toho`s Godzilla movies I also have some trepidations about it. I think it will have a tremendous effect on all the people involved in the production of Toho`s Godzilla films."29

Years later, actor Akira Kubo (SON OF GODZILLA, DESTROY ALL MONSTERS) expressed his own concerns about an American GODZILLA remake. "There have been leaps and bounds in filming techniques, in the way that they use computer graphics. In fact, I`m afraid that it might be too real," he warned. "Unlike the old films, little will be left to the imagination. How can you have a Godzilla that does not require you to dream?"30

As reference, Toho provided Sony Pictures with examples of the Godzilla design from their 1991 film GODZILLA VS KING GHIDORAH. Images courtesy of Jan De Bont. © Toho Co., Ltd.

As reference, Toho provided Sony Pictures with examples of the Godzilla design from their 1991 film GODZILLA VS KING GHIDORAH. Images courtesy of Jan De Bont. © Toho Co., Ltd.DEVELOPING THE STORY

"You can only hope that what you`ve done is respectful, and is at least as legitimate as what was done before." --GODZILLA (1994) screenwriter Terry Rossio

"The Big Mo" -- short for the Big Momentum -- was Peter Guber`s catchphrase. He felt the best way to get a movie made was to pile on so many positives (base the film on a hot property, get big stars, sign a name director) that no one in upper management could stop it.

With the GODZILLA contracts now signed, Guber admonished Cary Woods and Robert Fried to do just that. "I`ve done my bit," he told Woods. "Now it`s up to you to get this thing rolling. You have to give it momentum."1

The first order of business was to hire a writer and work out the story. There was never any intention of doing a direct sequel to any of the Toho movies; TriStar wanted a film that would be accessible to a worldwide audience beyond hardcore Godzilla fans. That necessitated a fresh start with an original story and characters. Fried felt that their GODZILLA would remain true to the classic series by cautioning against nuclear weapons and runaway technology, recurring themes in the Japanese movies.

The producers also had to decide how Godzilla would be portrayed in the new film. In the 1954 GODZILLA the monster had been a terrifying menace, but as the movies of the 1960s and 70s were increasingly aimed at younger audiences Godzilla gradually evolved into a heroic character. In the 1980s, Toho relaunched the series and returned Godzilla to his aggressive roots, but with enough leeway to allow audiences to sympathize with the monster.

FX director Koichi Kawakita was one of architects of the newer Toho films featuring an antagonistic Godzilla. "Godzilla has many overseas fans, but there`s probably a big gap between their perception of him and ours," he said. "They know him primarily from the sixties and seventies films, where he`s the lovable, comical figure. They really don`t know the changes we`ve made in him in the later movies."2

But Henry Saperstein was an avid supporter of Godzilla as a good guy. "Oh, they`re trying to be a little more villainous in the last two [Toho] films, but that`s not the way the new [American-made] feature is going to be," he argued. "It`s going to be pure Godzilla as we know and love Godzilla -- corny, lovable, klutzy, effective, a little scary, a little comedic. There`s a lot of humor in Godzilla."3 Saperstein added that, "He comes forth reluctantly to battle the evil forces, whether they`re outer-space aliens, or bacteria, or people."4

Cary Woods was leaning towards the "destructive but likeable" interpretation of Godzilla as seen in the recent Toho movies. In early 1993, he and Robert Fried invited a number of filmmakers -- including Tim Burton and PREDATOR screenwriters Jim Thomas and John Thomas -- to TriStar to pitch story ideas for GODZILLA. That March, they also asked famed British horror writer/filmmaker Clive Barker (Books of Blood, HELLRAISER) for his take on the property. While Barker did not write a full treatment, he did meet with the producers and presented a few pages of notes for a Godzilla story set around New York in December, 1999.

The project took its first significant step forward when Ted Elliott and Terry Rossio were hired to write the GODZILLA screenplay in May, 1993. While Elliott and Rossio have become two of the most commercially successful screenwriters in Hollywood -- their credits include THE MASK OF ZORRO (1998), SHREK (2001), and all four PIRATES OF THE CARIBBEAN movies -- in 1993, they had only two notable credits... the Fred Savage/Howie Mandel comedy LITTLE MONSTERS (1989) and a rewrite for Disney`s ALADDIN (1992). LITTLE MONSTERS had been produced by Vestron Pictures, which went out of business shortly after the film tanked at the box office. "It was a great credential," Elliott joked. "We could say that our script was the project that bankrupted Vestron."5

GODZILLA screenwriters Ted Elliott and Terry Rossio at the premiere of PIRATES OF THE CARIBBEAN: AT WORLD`S END.

GODZILLA screenwriters Ted Elliott and Terry Rossio at the premiere of PIRATES OF THE CARIBBEAN: AT WORLD`S END.But Ted Elliott and Terry Rossio had a supporter in Cary Woods, whom they had worked with during his time at William Morris. As Rossio described to SciFi Japan, "The way agencies work, a client often has more than one agent. For example, perhaps one agent for film, another that specializes in television. Or, one `junior` agent and then a `senior` agent to help out if needed. For a brief time, Cary Woods played that role for us -- not our primary agent, more of an advisor."

Woods knew that they had written well-received screenplays for two unproduced Disney sci-fi films; A PRINCESS OF MARS (an adaptation of Edgar Rice Burroughs` first John Carter novel) and ROBERT A. HEINLEIN`S THE PUPPET MASTERS (the film would be rewritten and released in 1994). "I guess we already had a reputation of handling franchise-type titles, such as ALADDIN and ZORRO," explained Rossio. Ted Elliott recounted that, "Cary called and said `Have you given any thought to your next project?` and we said, `We`re looking around.` He said, `Well, I`ve got one word for you: Godzilla.` And we said, `Uh, do you have any other words?` We actually turned the project down about two or three times because we weren`t sure we knew what to do with it."6

While neither writer was particularly enthusiastic about writing a GODZILLA screenplay, Cary Woods convinced them to come to TriStar and discuss the project. Elliott and Rossio wrote a three and half page GODZILLA story outline that got them the job. "You have to come up with a story that draws them in and excites them, then they give you the assignment," Rossio said. "Having gotten the assignment doesn`t necessarily mean anything; it just means you can write a script."7

Robert Fried expected that Elliott and Rossio would deliver a high-quality Godzilla story. "The writers of the screenplay are very talented sci-fi buffs and they were hired to write a very serious kind of sci-fi thriller," he enthused. "They weren`t engaged to write a schlocky type of movie. Another reason we`re excited about GODZILLA -- apart from the chance to spend large amounts of money on the effects, which everyone is expecting -- is because we`ve put a lot of time, thought and finance into the screenplay. So I think we`ll have a better thought-out storyline for our version of GODZILLA than you may have seen before."8

As TriStar began the task of finding a suitable director, Rossio and Elliott went to work on their first draft. Surprisingly, it was one of Toho`s many rules that helped the writers find a foundation to start from. "Toho insisted we not make light of the monster. That helped us find the right tone as well as the social and political implications," Ted Elliott stated.9 Terry Rossio explained, "Our intent was to take it quite seriously, in the sense of treating it like a legitimate science fiction story. We wanted to create an experience that would involve some true feeling for the audience in terms of being mystified or scared or awe-inspired, as opposed to having more of a comic approach."10 "Nobody`s doing the highland fling, let`s put it that way,"11 Elliott remarked, referring to Godzilla`s infamous victory dance in the Toho/Saperstein co-production, MONSTER ZERO.

Elliott and Rossio saw Godzilla as a territorial beast who didn`t like other monsters stomping on his turf. © 1964 Toho Co., Ltd.

Elliott and Rossio saw Godzilla as a territorial beast who didn`t like other monsters stomping on his turf. © 1964 Toho Co., Ltd."I think it would be a mistake to get totally away from some humanistic things [in Godzilla`s personality]," Rossio added. "As an example, if a submarine happened to shoot something at him, and he got hit from behind and turned around... that`s right on the edge, giving him a look like he`s pissed. But it would also be a mistake to completely humanize him. I felt you would not be happy going to a Godzilla film if you weren`t scared by Godzilla. There`s no getting around the fact that, if Godzilla`s in a fight people are probably going to root for Godzilla. But we felt it was really important that you be scared, that he be intimidating, that he be this force of nature. That you weren`t going to buddy up to Godzilla, you know, that you wanted to be scared by this giant thing. Thematically, Godzilla could be a metaphor for death, for example, for death is something you can`t stop. It`s destructive, it`s powerful."12

"I have a friend who is a big Godzilla fan," Elliott said. "He really likes Godzilla, he knows all the other monsters in the series, all that stuff. And he made the observation that became, for me, the key to what the story should be. What he said was, Godzilla`s not really a good guy. He is incredibly territorial, he just doesn`t like other monsters. And since most of the time those other monsters threaten humanity, Godzilla seems to be the defender of the Earth. But no, in fact, he`s just pissing in his own territory, getting rid of anybody who interferes. And that, to me, meant that you could actually present Godzilla on the side of the angels but he could still be a monster."13

Elliott also wanted Godzilla to be believable onscreen as a living creature. "One of the things we suggested is that he actually have the nictitating eyelid -- a secondary eyelid for when he`s underwater -- like a crocodile does," he revealed. "Just little things that can make him seem more realistic. That`s a weird word to use with Godzilla, but that`s the intent."14

Detailing their concept for the story, Elliott said, "There are two protagonists, a man and a woman. It`s really kind of funny... basically, our approach was to do a Moby Dick story, in which the scientist`s wife or husband is killed by Godzilla in his first appearance. Now this person wants to hunt Godzilla down and kill it. As it developed, it seemed more interesting for it to be a woman character whose husband was killed. And by the time we finished the movie, it occurred to us that it was very similar to ALIENS, in which Ripley`s obsessed -- she`s Ahab. So I also wondered if [James] Cameron started with an Ahab story, the same as we did. It`s a story about obsession and redemption... and inappropriate grief response. But a lot of what we wanted to do was give Godzilla to Godzilla fans. And in one movie it does what the first three Toho films did -- it takes him from being a horrendous threat to being defender of the Earth."15

Cary Woods and Robert Fried were extremely pleased with Elliott and Rossio`s first draft. "They wrote a beautiful original screenplay," Fried raved, "respectful of the organic origins of Godzilla, in some ways a homage to US-Japanese relations. There was a new character, a new foe for Godzilla. They did a really good job."16 Marc Platt, president of production for TriStar, concurred: "This is going to be a serious-minded monster movie, a large-scope sci-fi film steeped in mythology."17

But Terry Rossio was curious how longtime Godzilla fans would respond to his and Elliott`s take on the character. "I think it`s a fascinating question, about how a US company treats this franchise versus how it was originally treated," he acknowledged. "In terms of being disrespectful to the creature, I don`t think we have been and don`t think we could have been, based on the restrictions Toho had put in place, and so far they`ve been approving of everything. You can only hope that what you`ve done is respectful, and is at least as legitimate as what was done before."18

Click on the above image to read the complete final draft GODZILLA screenplay by Ted Elliott and Terry Rossio. © Terry Rossio and Ted Elliott

Click on the above image to read the complete final draft GODZILLA screenplay by Ted Elliott and Terry Rossio. © Terry Rossio and Ted ElliottTHE SCREENPLAY

"Godzilla will kill it." --GODZILLA screenplay by Ted Elliott and Terry Rossio

On November 10, 1993, Ted Elliott and Terry Rossio submitted their first draft screenplay for GODZILLA to TriStar. The following synopsis is taken from that first draft...

In a remote location somewhere on the frozen coast of Alaska, a salvage ship excavates nuclear reactor cores that were illegally dumped at sea long ago by the Soviet Union. Suddenly, something goes awry and a huge explosion destroys a ship. On the shoreline, giant snow banks mysteriously catch fire and a huge crevice opens in the ground, streaming an eerie red-black fluid.

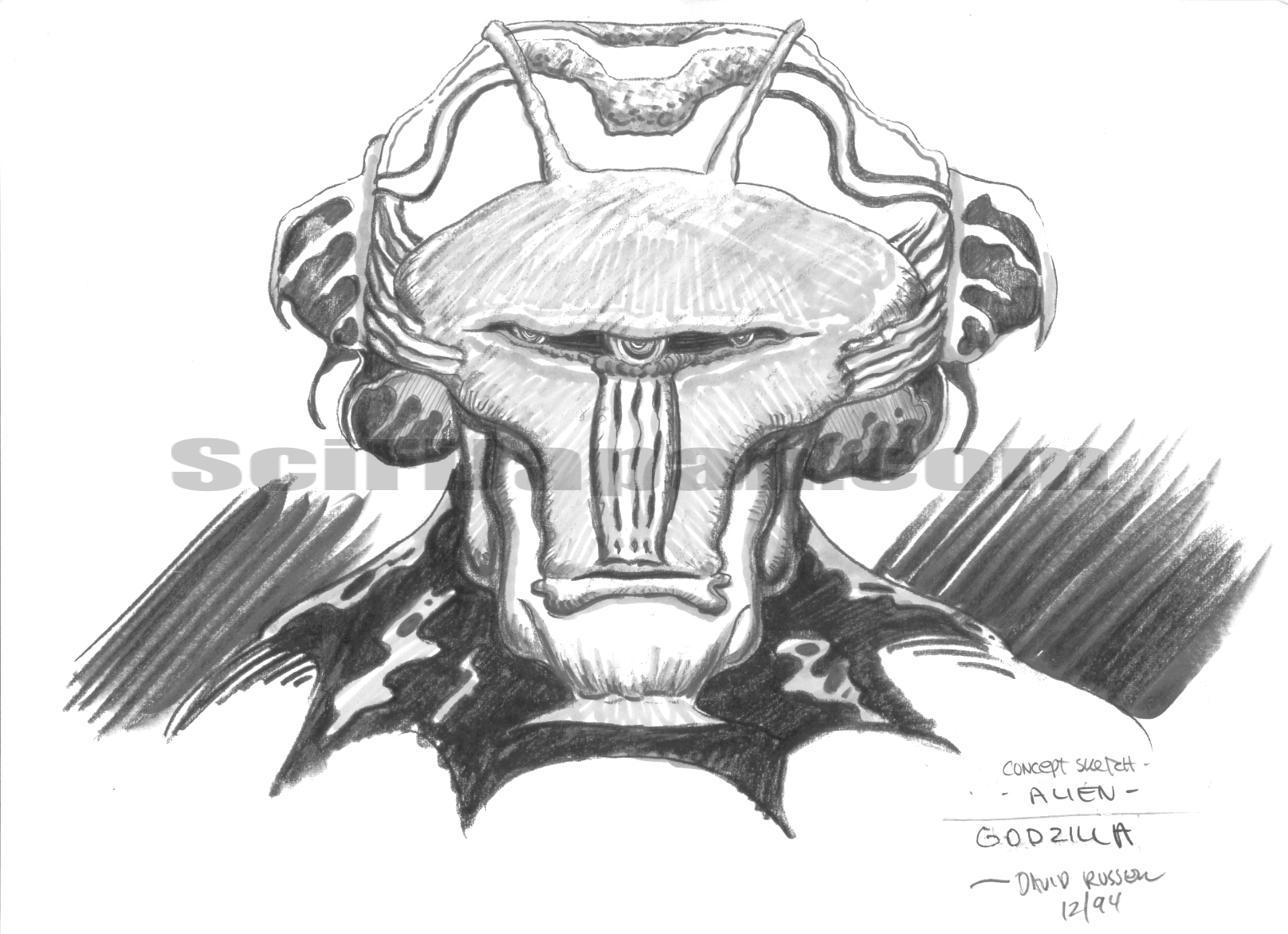

Concept art of Godzilla`s ice cave by Ricardo Delgado. Image courtesy of Jan De Bont. © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.

Concept art of Godzilla`s ice cave by Ricardo Delgado. Image courtesy of Jan De Bont. © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.In the middle of the night, Dr. Keith Llewellyn, a government scientist, is flown to the site of the accident, where the military has launched a top secret investigation into the giant fissure in the ground (there`s a scene where he regretfully leaves behind his wife, Jill, and young daughter Tina, both of whom figure in the story later). Soldiers cart away drums full of the mysterious red-black liquid which, tests show, resembles an amniotic fluid (the substance fetuses gestate upon in the womb). In the underground cavern, Keith sees what at first appears to be a huge stalactite formation but, upon inspection, is actually the claws of a huge creature imbedded in the sediment. Keith finds the head of the perfectly preserved creature -- a huge dinosaur -- and climbs atop its muzzle to look down the length of its 247-foot-long body.

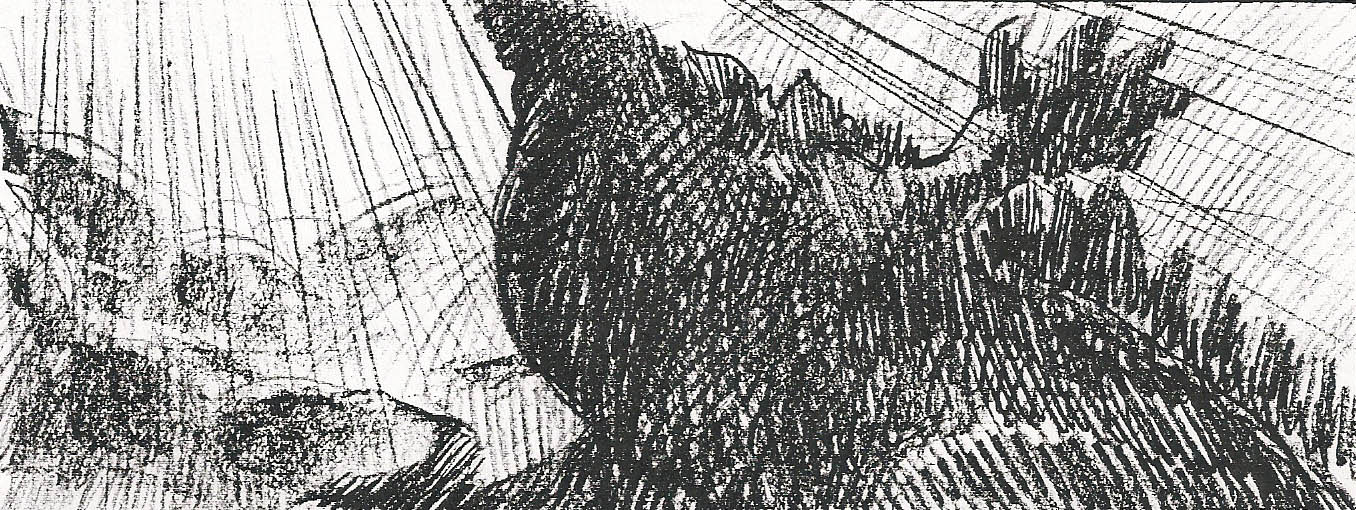

Suddenly, the beast opens one of its eyes... it`s alive!... and breaks free from the ice. Everyone in the cavern is crushed, and the beast destroys the entire military camp, then heads south into the sea. Soon thereafter, the dinosaur appears at the Kuril Islands off Japan and destroys a village. It is seen by a fisherman who believes it is Godzilla, a legendary monster.

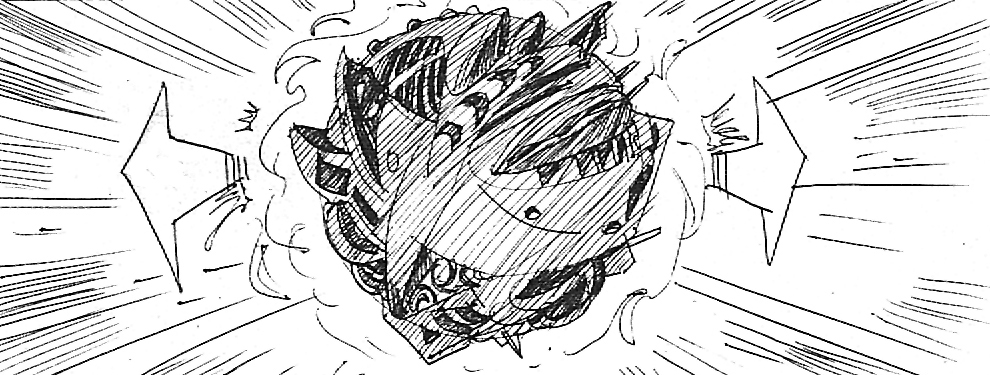

Fast-forward 12 years later. Aaron Vaught, a pseudo scientist whose theories about dragons and dinosaurs have made him a best-selling author, and Marty Kenoshita, his assistant, sneak into a Japanese mental hospital to visit Junji, the fisherman who saw Godzilla. Junji shows Vaught his drawings of Godzilla, images that come to him in his dreams. In one picture, Godzilla is locked in battle with a Gryphon, leading Aaron and Marty to theorize that if Godzilla exists (as they think he does), he must have an adversary. Just then, military police arrive to escort Vaught and Marty out of the country. The men think they`re being busted for sneaking into the hospital, but actually the government has a mission for them. Meanwhile, in rural Kentucky, a huge fireball plunges into Lake Apopka, eerily raining fish and frogs on a nearby town.

Godzilla`s breath ionizes the air, creating a blast of radioactive fire. Art by Giacomo Ghiazza. Image courtesy of Terry Rossio. © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.

Godzilla`s breath ionizes the air, creating a blast of radioactive fire. Art by Giacomo Ghiazza. Image courtesy of Terry Rossio. © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.Jill Llewellyn, Keith Llewellyn`s widow, is now director of the top-secret St. George Project in Massachusetts, a military effort to find the beast that caused the Alaska disaster. The monster was last seen six years ago, when it destroyed an oil tanker. Jill is not pleased to learn that Vaught, the dragon enthusiast, who she dismisses as a "folklorist", will be co-director of the project with her -- Jill`s superiors hope Vaught`s popularity will help the project get funding from Congress.

In the midst of this conflict, Jill gets a call from the base police: Tina, now 16, is being detained for trying to steal a car. The relationship between the working mom and rebellious teen is loving, but strained.

Back at the "Godzilla womb" site in Alaska, where a military installation has been established, two guards see streams of peculiar light streaming from a yet-unexplored ice cave and illuminating the sky. At the same time, a mysterious alien probe -- metallic, yet alive -- is stirring at the bottom of Lake Apopka. Flowing like liquid chrome, the probe enters a cave, grabs dozens of bats, and absorbs them into its own matter. The probe then forms dozens of "Probe Bats", evil creatures with 12 foot wingspans that sail out of the cave and into the night sky.

Vaught, Marty, and Jill fly to Alaska and discover that red-black amniotic fluid has been flowing from Godzilla`s womb, and Aaron deduces that today is -- or was supposed to be -- Godzilla`s birthday, had the monster not been released prematurely. The trio enters a newly opened ice cave, which is lined with intricate organic formations, a strange remnant of an ancient civilization with advanced biotechnology. No one notices when a microscopic alien organism swoops down and burrows into Marty`s neck, not even Marty.

Another chain of events: In Kentucky a stable of milk cows is slaughtered overnight, their carcasses removed of limbs and organs; in the Pacific Ocean, three fishing boats are capsized when Godzilla, pursuing a school of fish, passes beneath at 40 knots. Another sighting is reported when Godzilla passes beneath an oil tanker, and the military figures he is heading for San Francisco.

Godzilla battles the US Navy near San Francisco. Art by Ricardo Delgado. Image courtesy of Jan De Bont. © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.

Godzilla battles the US Navy near San Francisco. Art by Ricardo Delgado. Image courtesy of Jan De Bont. © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.Jill and Vaught go to the Presidio, where a command post is set up, but Marty has become ill and is taken away for medical care. Two missile carriers, a battleship, and a submarine are sent to intercept Godzilla, but the monster easily destroys two planes then submerges and throws one of the missile carriers out of the sea, cracking it in half. Godzilla finishes off the ships by emitting a fiery breath that turns the hulls to molten metal.

The military considers using a small nuclear bomb to stop Godzilla, but Vaught believes it won`t work: Godzilla is a living, breathing nuclear reactor -- evidence by the fact he breathes not flame, but something so hot it actually ionizes oxygen.

Jill concludes that the red-black fluid that encased Godzilla was not food, but actually a tranquilizer that kept the monster in hibernation. Barrels of the fluid are brought to San Francisco and a plan is concocted to stop Godzilla using the red-black stuff. Fire trucks spray the surface of the water entering the bay with the fluid, and as Godzilla arrives, he swims right into the trap. He bolts upright and slowly comes ashore, then, roaring weakly, collapses on the south side of the Golden Gate bridge.

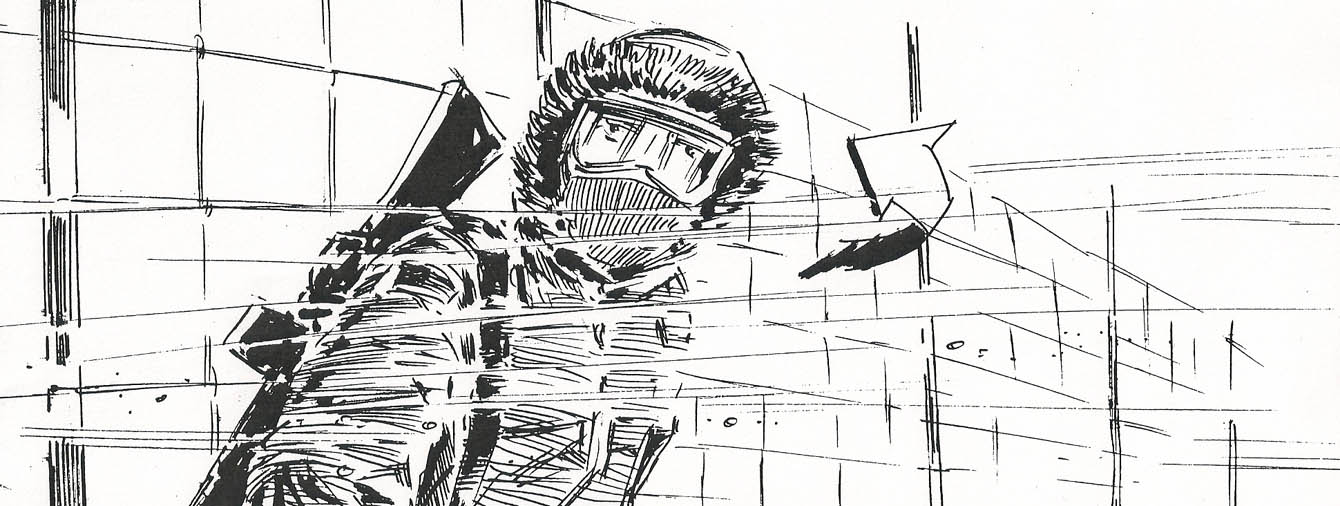

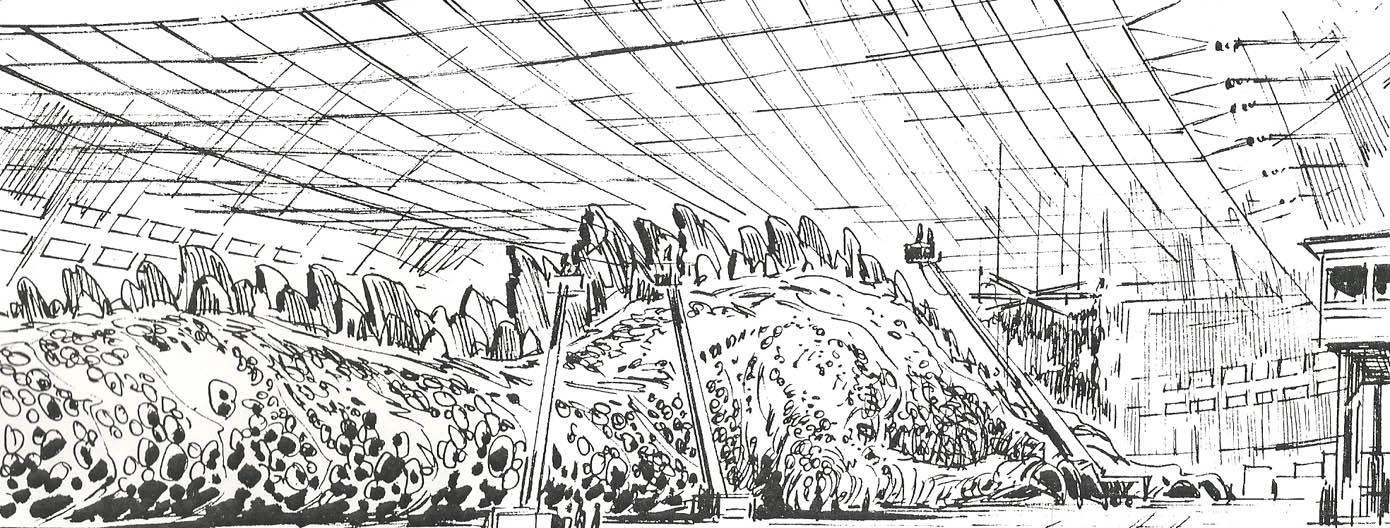

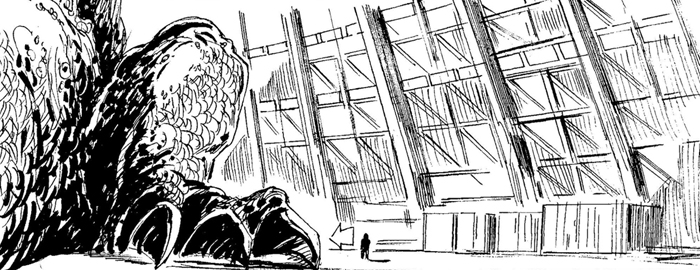

Using six super-helicopters, the military transports Godzilla, suspended from cables, to Massachusetts, where it is stored in a huge hangar, the tail sticking out one end.

One night, young Tina sneaks into the hangar and suddenly realizes that mom`s job for the past 12 years has been hunting the beast that killed her Dad. Tina, wise beyond her years, says Godzilla is a force of nature and should be respected. Her mother sends Tina to Manhattan to stay with an aunt for a while.

At a military hospital, Marty`s infection is consuming his internal organs, and has turned his face into a flat, eyeless surface. Whatever has invaded his body is taking over, and begins speaking through him. Before he dies, Marty tells Jill about an alien race colonizing the universe by sending out probes that create a "doomsday beast" out of the local genetic material -- by the time the alien colonists arrive, the beast has already conquered the planet. An ancient, biotech Earth civilization guarded itself against these invaders by creating Godzilla out of dinosaur genes, placing him in suspended animation to awaken when the alien probe arrives and kill it before it can reproduce. Meanwhile in Kentucky, the alien Probe Bats keep absorbing critters and bringing them back to the cave, where a mysterious creature is slowly taking shape.

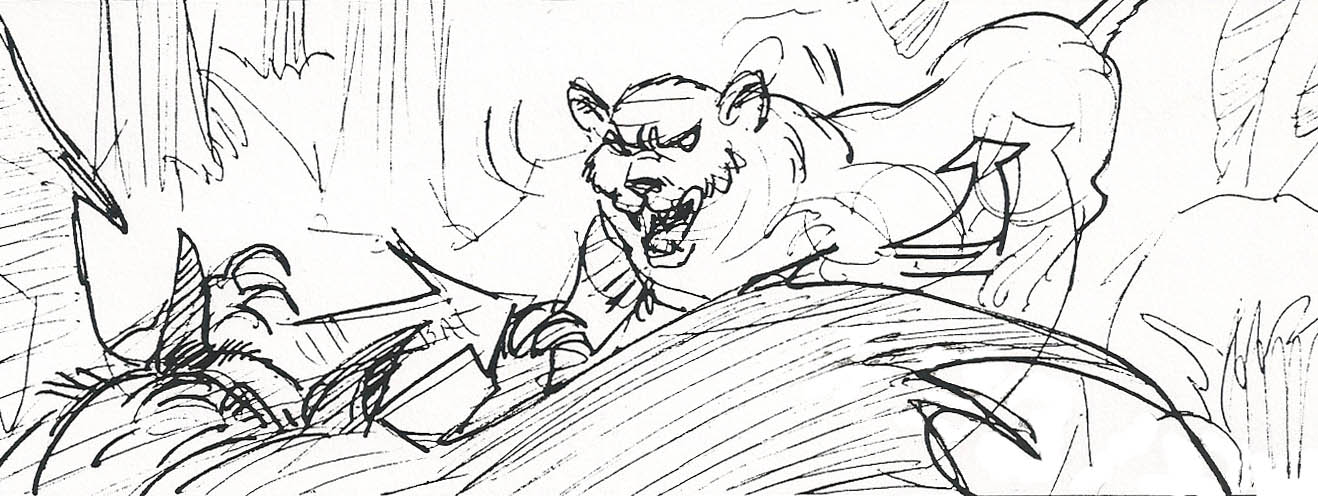

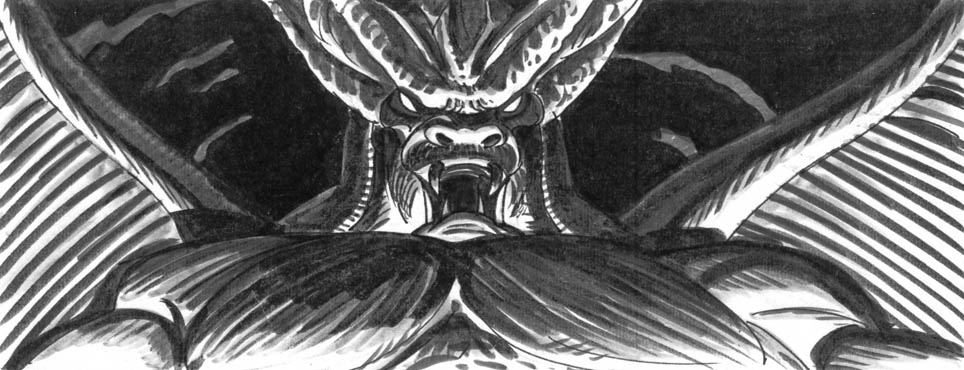

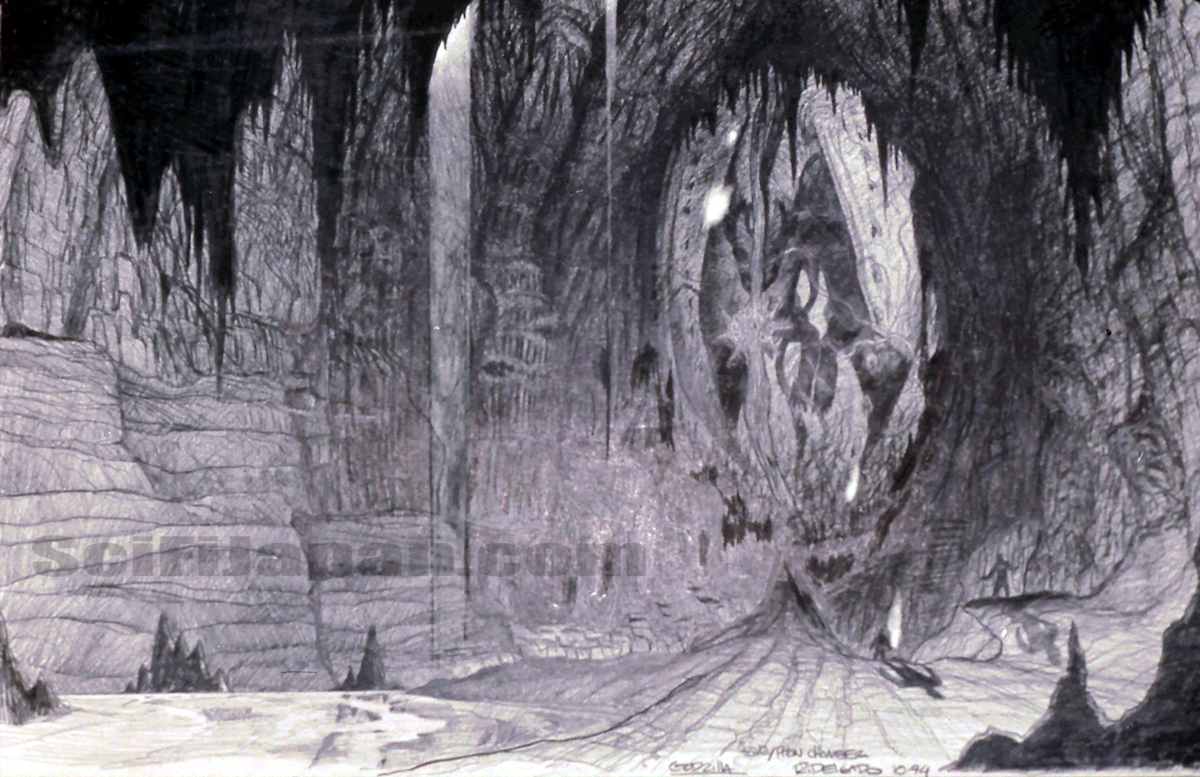

The Gryphon emerges from its lair in a storyboard by artist David Russell. Image courtesy of David Russell. © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.

The Gryphon emerges from its lair in a storyboard by artist David Russell. Image courtesy of David Russell. © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.Vaught deduces that Godzilla was headed for the spot where the huge fireball landed, and immediately goes to Kentucky. There, Vaught is driven to Lake Apopka by Nelson Fleer, a local storekeeper (who keeps using the phrase, "weird shit," for comic effect). The men don diving gear and explore the lake bottom, and discover a tunnel that leads to a series of caves. Vaught finds what first appear to be a giant paw and, upon further inspection proves to be attached to the Gryphon, a giant monster with the body of a cougar, wings of a bat, and a tongue of snakes, created by the alien probe out of the smaller creatures.

The dormant monster is awakened when Fleer clangs one of his diving tanks against a rock. The men submerge and swim for safety, and the huge monster`s roar is heard behind them; when they reach the lake`s surface, all seems normal for a moment until the monster rises with a roar and takes to the air.

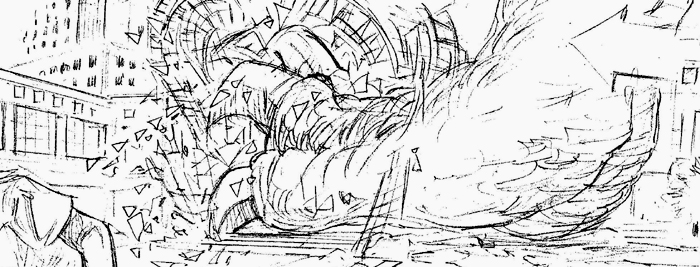

Flying north the Gryphon terrorizes Clarksburg, Virginia, where it derails a train, kills people, and fires energy bolts that destroy a gasoline storage tank. Back in Massachusetts, Godzilla senses his rival`s appearance and awakens, despite a constant stream of amniotic fluid being force-fed to him. The great beast destroys the hangar and walks to the shoreline, where he drops down on all fours before going into the water.

The arch-enemies are heading straight for each other and if they hold course, they`re set for a showdown in New York City. As Manhattan is evacuated, Jill tries desperately to drive into the city, hoping to save Tina. When Godzilla steps on the Queens Midtown tunnel, Jill is briefly trapped under water, but she swims to safety and, just as she reaches dry land, Godzilla`s foot comes down, narrowly missing her. As the battle of the monsters begins, Jill finds Tina and they try to figure out how to get off the island safely.

The Gryphon takes flight and crashes into Godzilla, knocking him back to the shore. Godzilla wraps his tail around the frame of an under construction building, then pulls the Gryphon near and bites its leg. The Gryphon`s wounds heal instantly, miraculously, and the beast then retaliates with energy bolts that knock Godzilla back into the rows of buildings. The Gryphon keeps charging, scratching Godzilla with its talons. Helicopters circle the city, while the Gryphon flies overhead, hunting Godzilla. The two beasts again slam into one another and begin to wrestle, tumbling into a skyscraper. The Gryphon double-kicks Godzilla in the belly, sending him flying into another building, which falls on both monsters.

The Gryphon perches on the Statue of Liberty. Art by David Russell. Image courtesy of Jan De Bont. © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.

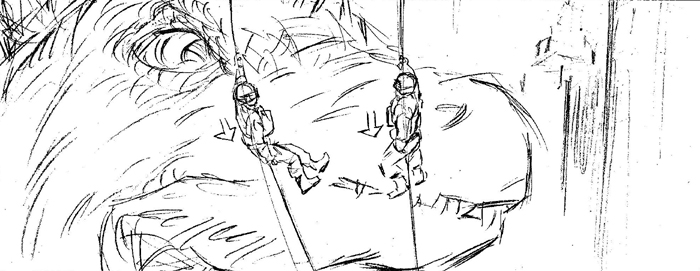

The Gryphon perches on the Statue of Liberty. Art by David Russell. Image courtesy of Jan De Bont. © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.Vaught says Godzilla can`t beat the Gryphon because of a restraining device implanted in the monster`s neck by the military, which gives him a constant dose of the fluid and prevents him from breathing fire. Using gunship helicopters, the military diverts the Gryphon while Vaught and Fleer remove the device from Godzilla, who lays stunned next to a building. From a helicopter, the men are lowered on wires onto Godzilla, but the Gryphon blasts the chopper and the men are stranded atop the monster. As Fleer and Vaught rig explosives to destroy the restraining device, Jill and Tina stall the Gryphon briefly by crashing a gasoline tanker into the monster.

The restrainer is removed from Godzilla just before the Gryphon arrives; now Godzilla fires his breath at his opponent, wounding him, and pursues the fleeing Gryphon more vigorously. The battle royal takes place in the East River. Godzilla breathes fire across the water`s surface, creating a steam cloud that blinds the Gryphon and causes it to crash into the Brooklyn Bridge and get tangled in the cables. Godzilla bites one of the Gryphon`s wings off but the monster`s healing properties instantly reattach the limb.

Then the Gryphon climbs skyward, turns around, and power dives. Godzilla waits for his foe, then suddenly bends forward at the last moment and the Gryphon is sliced open on Godzilla`s dorsal plates. Godzilla pulls his adversary into the river, rips its head off and sets fire to the body. Godzilla, though badly wounded, roars victoriously and sets out for the sea. Jets move in to kill the wounded beast, but Jill convinces the military commander to call off the strike. She has finally forgiven the monster.

From the shore, Jill, Tina, Aaron, and Fleer watch Godzilla go home.1

After Jan De Bont joined the project, Rossio and Elliott revised the script based on the director`s input. Among the changes: the timeline of events was condensed to a single year rather than 12, both Jill and Keith are flown to the Arctic site, Keith first spots Godzilla`s teeth (rather than his claws) buried in the ice, and the alien probe crash-lands near Traveller, Utah instead of Kentucky. The complete final draft of the GODZILLA screenplay (dated December 9, 1994) can be read and downloaded at Terry Rossio and Ted Elliott`s website, Wordplay.

Diagram of New York City and surrounding areas showing the movements of Godzilla and the Gryphon. Image courtesy of Terry Rossio. © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.

Diagram of New York City and surrounding areas showing the movements of Godzilla and the Gryphon. Image courtesy of Terry Rossio. © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.DIRECTOR HUNT

"It seemed like a natural, but you`d be surprised how many writers and directors passed on the project initially." --GODZILLA (1994) producer Robert Fried

"I was never a big Godzilla fan." --GODZILLA (1998) writer/director Roland Emmerich

In their first article on TriStar`s GODZILLA back in October 1992, the Los Angeles Times reported that, "Several directors have reportedly already expressed interest in the project... BATMAN`s Tim Burton is among the names mentioned in connection with the project."1 But in mid-1993 producers Cary Woods and Robert Fried found that things were not turning out as expected. They wanted a recognizable "name" director, but GODZILLA was again proving to be a tough sell.

Based on a recommendation from Chris Lee, Woods and Fried first offered GODZILLA to Roland Emmerich and his writing/producing partner Dean Devlin. After directing a handful of English language films in his native Germany, Emmerich had come to the United States and made his first American movie -- the sci-fi action film UNIVERSAL SOLDIER starring Jean-Claude Van Damme and Dolph Lundgren -- which TriStar distributed in 1992.

Years before, Emmerich had pitched one of his German productions, MOON 44 (1990), to Lee and (while Lee had passed on the movie) the two had become friends. Lee had a knack for recruiting and nurturing new filmmakers at Sony, and Emmerich would turn to him as a sounding board for potential projects. The two would occasionally meet at TriStar to chat, and Chris Lee often brought up his interest in doing an American GODZILLA film. But Emmerich couldn`t understand Lee`s enthusiasm for the property. "I was never a big Godzilla fan," acknowledged Emmerich. "They were just the weekend matinees you saw as a kid, like Hercules films and the really bad Italian westerns. You`d go with all your friends and just laugh."2

He was further surprised that Sony thought the project would interest him. “We got approached with GODZILLA, and Dean was really in favor. I said, ‘Are you crazy? Have you seen a Godzilla film? How does the monster look? They put a guy in there.’”3

Roland Emmerich and Dean Devlin quickly rejected the GODZILLA offer. "We just thought, `How do you overcome the cheese factor?`," Devlin recalled. "We talked about it and all we could see was farce. We could see the joke... we couldn`t see the movie.4 We really didn`t know how to make it properly, and so we passed on it."

One name that kept popping up in the early GODZILLA news reports as a possible director was Tim Burton. The quirky Burton was definitely the type of A-list filmmaker Woods and Fried were looking for; he had directed a string of box office hits that included PEE-WEE`S BIG ADVENTURE (1985), BEETLEJUICE (1988) and EDWARD SCISSORHANDS (1990), and produced THE NIGHTMARE BEFORE CHRISTMAS (1993). More importantly he had made two certified blockbusters -- BATMAN (1989) and BATMAN RETURNS (1992) -- which had earned a combined total of $683 million worldwide. And Burton was known to be a Godzilla movie fan, even using Godzilla and King Ghidorah for a comedic cameo in PEE-WEE`S BIG ADVENTURE.

"I know that Tim Burton was interested and was called in to pitch a version," screenwriter Terry Rossio said. But there were concerns among some of the crew about how he would have handled the material. "I actually think Tim Burton wouldn`t have been right for this movie. If he did a GODZILLA film, he might intentionally make it campy or a guy in a rubber suit. We took a totally different approach, which was to say, `Let`s take it all seriously and imagine that you could wake up one morning, walk out your front door, look up at the horizon and see Godzilla there, stomping towards you`."5 Talks with Burton stalled, and the director moved on to other projects such as ED WOOD (1994) and MARS ATTACKS! (1996).

The producers also approached Joe Dante, who had directed the cult favorites PIRANHA (1978) and THE HOWLING (1981), as well as the hit GREMLINS (1984). While many of his films featured monsters and sci-fi/fantasy elements, Dante expressed skepticism over GODZILLA as a major Hollywood production. "They asked me about it but I haven`t seen anything. I don`t know what the story is yet," he revealed in the summer of 1993. "They have quite a job ahead of them trying to turn Godzilla into what they`re talking about, which is a movie that will attract major stars. I don`t know what you do with that time-worn plot that can be `new` enough to make it something special, but the jury`s out."6 Dante would later be attached to direct GODZILLA REBORN, a proposed American sequel to Toho`s GODZILLA 2000 (ゴジラ2000 ミレニアム,, Gojira Nisen Mireniamu, 1999).

Among the directors Woods and Fried said that they and TriStar considered were three future Academy Award winners. James Cameron had a strong track record of movies such as TERMINATOR (1984), ALIENS (1986), and TERMINATOR 2: JUDGMENT DAY (1991) that were both financially successful and critically praised. In 1993 he was directing TRUE LIES (1994) and developing SPIDER-MAN. Asked about GODZILLA, Cameron related that, "It was presented to me as an interesting script," but was not something he ever considered directing.7

The project was turned down by Ridley Scott, the director of the sci-fi classics ALIEN (1979) and BLADE RUNNER (1982), and mainstream hits like the recent THELMA & LOUISE (1991). BACK TO THE FUTURE trilogy (1985-1990) and WHO FRAMED ROGER RABBIT director Robert Zemeckis also passed.

In a surprising note, the directing team of Joel and Ethan Coen had been possible candidates for GODZILLA. The Coen Brothers seemed like an odd choice... while displaying a unique visual sense they had never done a sci-fi movie, alternating instead between violent, noirish tales like BLOOD SIMPLE (1984), MILLER`S CROSSING (1990) and BARTON FINK (1991), and quirky comedies such as RAISING ARIZONA (1987) and THE HUDSUCKER PROXY (1994). Their body of work includes a number of acclaimed films, among them FARGO (1996), THE BIG LEBOWSKI (1998), OH BROTHER WHERE ART THOU? (2000), NO COUNTRY FOR OLD MEN (2007, for which they won Academy Awards for Best Picture and Best Director) and TRUE GRIT (2010). "That was my idea," Cary Woods admitted. "I had just seen THE HUDSUCKER PROXY at Sundance and thought they could give GODZILLA a cool, young twist. Then when HUDSUCKER came out and did no business whatsoever the studio wanted to put me in a straightjacket."8

Sony never made an offer to the Coens. "They weren’t going to put them on a $120 million movie,”9 Woods said, admitting that it was unlikely the brothers would have even agreed to a meeting for a Godzilla movie.

Monty Python`s Terry Gilliam was also considered. Gilliam had co-directed the classic MONTY PYTHON AND THE HOLY GRAIL (1975) and directed TIME BANDITS (1981), BRAZIL (1985), and THE FISHER KING (1991). He was known for his talent, for being meticulous, and for sticking to his guns when dealing with studios... which often made executives extremely wary about hiring him for big budget productions. Regardless of his reputation, Terry Gilliam was already busy at TriStar on CARTOONED and developing projects such as 12 MONKEYS (1995) for other film companies.

Also looked at were some up-and-coming filmmakers that hadn`t (at that time) achieved the status of a James Cameron or a Ridley Scott. Cinematographer-turned-director Barry Sonnenfeld had scored hits with THE ADDAMS FAMILY (1991) and it`s sequel, ADDAMS FAMILY VALUES (1993), and would go on to do MEN IN BLACK (1997), the biggest box office hit to date for Columbia Pictures. Sam Raimi was known for his EVIL DEAD trilogy (1981-1992) and DARKMAN (1990); his future would include the blockbuster SPIDER-MAN trilogy (2002-2007) for Columbia. Former FX artist Joe Johnston had directed HONEY I SHRUNK THE KIDS (1989) and THE ROCKETEER (1991), and would find further success with JUMANJI (1995), JURASSIC PARK III (2001), THE WOLFMAN (2010), and CAPTAIN AMERICA: THE FIRST AVENGER (2011).

GODZILLA was not offered to Steven Spielberg. The director had praised the original film, saying, "GODZILLA, of course was the most masterful of all the dinosaur movies because it made you believe it was really happening."10 But Spielberg was busy with post-production and publicity for JURASSIC PARK and prepping to shoot SCHINDLER`S LIST, making him unavailable for the foreseeable future.

Meanwhile, British director Alex Cox (REPO MAN, SID AND NANCY) applied for the GODZILLA gig, but not to the producers or TriStar. Rather, he sent an open letter to the prestigious Japanese film magazine Kinema Junpo (Cinema Jump) requesting the job from Toho. Cox wrote, "Godzilla is one of the most important icons of the post-atomic age. Perhaps she is the most important. I assume Godzilla is a she, given that she has produced at least one son. And perhaps this has something to do with her great popularity: who could not love a giant, angry, fire-breathing dinosaur who was also a mother?"

Alex Cox`s gender-confused efforts proved unsuccessful, but did launch rumors -- repeated for months in Godzilla fan circles -- that he would be directing TriStar`s film. The attention Cox received would later result in some Godzilla assignments of a different sort; he wrote a four-issue story arc for the Godzilla comic book series published by Dark Horse in 1996, and served as narrator for the 2008 documentary BRINGING GODZILLA DOWN TO SIZE from Classic Media.

As 1993 wound down, changes were brewing at the Sony Pictures offices. On January 7, 1994, Mike Medavoy was fired from his post as chairman of TriStar Pictures and replaced by Mark Canton. A former vice president of production for Warner Bros, Canton had been brought to Sony in October 1991 by his old friend Peter Guber and made chairman of Columbia Pictures. His reign at Columbia had been decidedly hit and miss; in 1993 alone he had two very expensive box office failures -- LAST ACTION HERO and GERONIMO: AN AMERICAN LEGEND -- but he, unlike Medavoy, got along well with Guber and that made all the difference. With Medavoy`s removal, Mark Canton would oversee both Columbia and TriStar as head of production for Sony Pictures. There was a brief pause in GODZILLA`s development as Canton was brought up to speed on the project and requested some minor changes to the screenplay. But before long Cary Woods and Robert Fried were back on the hunt.

In early May 1994, TriStar put the word out via the industry trades that they were still looking for a filmmaker to take on GODZILLA. The studio set a May 20th deadline to find a suitable director, but that date came and went with no deal in place. The "Big Mo" Peter Guber wanted for the project was slipping away. The producers were growing increasingly frustrated by the drawn-out process.

"The thinking was to take a classic legend that was renowned for its campy effects and make it seriously, applying big-budget, American technology," Robert Fried vented. "It seemed like a natural, but you`d be surprised how many writers and directors passed on the project initially. They just didn`t realize the commercial potential. And many simply lacked an inspired idea for how to make it, an approach to the material that was unique."11

Back in Tokyo, executives at Toho expressed their own frustration. The Japanese studio had planned to end production of their own Godzilla movies with the 1993 entry GODZILLA VS MECHAGODZILLA II (ゴジラvsメカゴジラ, Gojira Tai Mekagojira). But with no American GODZILLA in sight, Toho decided to forge on. "No one knows when it will be released," observed Godzilla series producer Shogo Tomiyama. "Every year we waited to see if TriStar would produce its Godzilla film before deciding to produce another one of our own. We got tired of doing that."12

Toho would eventually make two more Godzillas -- GODZILLA VS SPACEGODZILLA (ゴジラvsスペースゴジラ, Gojira Tai SupēsuGojira, 1994) and GODZILLA VS DESTOROYAH (ゴジラVSデストロイア, Gojira Tai Desutoroia, 1995) -- before bringing the series to a temporary end. Henry Saperstein was more upbeat, declaring, "I guess my crowning glory will be when TriStar`s movie is released sometime in mid-Summer 1995."13

“Another Godzilla movie begins.” In Japan, a teaser trailer for the TriStar GODZILLA was shown with Toho`s 1993 release GODZILLA VS MECHAGODZILLA II. This would be the only trailer ever produced for the first version of the film. © 1993 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.

“Another Godzilla movie begins.” In Japan, a teaser trailer for the TriStar GODZILLA was shown with Toho`s 1993 release GODZILLA VS MECHAGODZILLA II. This would be the only trailer ever produced for the first version of the film. © 1993 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.THE FIRST FX TEST

"[Sony] wanted to keep the classic, original design and define his body structure with more musculature." --GODZILLA (1994) scannable maquette sculptor Jeff Farley

As the search for a GODZILLA director continued into June 1994, Sony Pictures Imageworks (CONTACT, STARSHIP TROOPERS, SPIDER-MAN trilogy, AMAZING SPIDER-MAN series) prepared their bid to do the digital effects for the film. Established in 1992, Imageworks had created visual effects for a handful of movies, including shots of a bus jumping a gap in a freeway overpass for director Jan De Bont`s hit, SPEED. As a division of Sony Pictures, the company seemed an obvious choice to work on the studio`s GODZILLA but was still required to apply for the assignment with a CGI test.

Imageworks needed scannable maquettes of Godzilla for the test, and they needed them quickly so art director Jon Townley turned to artist and model maker Michael Hood (STAR TREK: THE NEXT GENERATION, THE ABYSS, TEENAGE MUTANT NINJA TURTLES III, ULTRAMAN: THE ULTIMATE HERO) at Precision Effects to sculpt prototypes of the monster`s head and entire body.

With only a few days to do both maquettes, Hood quickly decided to share the workload with Jeff Farley and his team at Obscure Artifacts. Despite the incredibly tight deadline, Farley was very happy for the opportunity to be involved in a Godzilla film. "It was my love of Godzilla, Ray Harryhausen and the genre as a whole that spurred me to consider a career in the special effects industry," he told SciFi Japan. "I recall hearing about the original film from my mom and dad when I was a kid. It was running on a local TV station late one night and they let my brother and me stay up to watch it. I was hooked and started to watch every kaiju film I could find. One station used to run them 6 nights a week and I`d watch them every single night. These films are a part of so many peoples childhood dreams and I am no exception."

Jeff Farley grew up in Glendale, CA. As a youngster, he became friends with Forrest Ackerman, creator of Famous Monsters of Filmland magazine, and with Forry`s support he began contacting professional FX artists like Jim Danforth (WHEN DINOSAURS RULED THE EARTH), Dennis Muren (STAR WARS), David Allen (EQUINOX) and Rick Baker (AN AMERICAN WEREWOLF IN LONDON). "I started to call and bug them. They were incredibly nice and answered all of my questions and would invite me over to meet them, so I had this very lucky childhood. One of the editors of STAR WARS, Richard Chew, also lived a few houses away from mine and I would spend a lot of time there. I could see that it not only took talent, but sheer determination to enter the industry so I made it my one driving force."

Farley was an apt pupil, and broke into to the FX business while still in high school. "It was my connection with Forry that got me my first job," he explained. "Meeting Ray Harryhausen put me in touch with a guy named Douglas Barrett Jones who had been working at The Burman Studios. He was then working on KINGDOM OF THE SPIDERS and invited a couple of my friends and me to help make background spiders."