Jan De Bont quickly assembled a team to create concept art, maquettes and storyboards for GODZILLA. © 1993-1995 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.

Jan De Bont quickly assembled a team to create concept art, maquettes and storyboards for GODZILLA. © 1993-1995 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.Director Jan De Bont is Hired and Pre-Production Begins

Author: Keith Aiken

Special Thanks to: Please See ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS in Part 1

A SCIFI JAPAN EXCLUSIVE

- FACE TO FACE WITH THE MISSING LINKS

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- ORIGINS

- DEVELOPING THE STORY

- THE SCREENPLAY

- DIRECTOR HUNT

- THE FIRST FX TEST

Part 2

- JAN De BONT

- PRE-PRODUCTION BEGINS

- CONCEPTUAL DESIGN, ROUND ONE: GOJIRA PRODUCTIONS and STAN WINSTON

- STORYBOARDS

- DIGITAL EFFECTS

- CONCEPTUAL DESIGN, ROUND TWO: WINSTON STUDIO

- FINAL PREPARATIONS: CASTING plus MINIATURE and PRACTICAL EFFECTS

- THINGS FALL APART

- RETRENCHMENT

- THE REWRITE

- THE DISCONNECT

- REACTION

- AFTERMATH

- GODZILLA (1994) CREDITS

JAN De BONT

"It’s like some people fall in love with westerns or other things. I loved Godzilla movies." --GODZILLA (1994) director Jan De Bont

Cary Woods and Robert Fried`s first-look production deal with Sony Pictures expired in June 1994 and, eager to pursue their own separate projects, the two decided not to renew their contracts. Fried signed a multi-year deal with Savoy Pictures while Woods negotiated with Disney to develop and produce films for Hollywood Pictures and Miramax. Despite the end of the Woods/Fried partnership, the producers continued to work together on the films already in development at Sony, and finally -- after months of false starts and headaches -- scored a major coup when Jan De Bont signed on to direct GODZILLA in the first week of July, 1994.

Born in Eindhoven, Netherlands, De Bont had studied at the National Film Academy in Amsterdam, becoming proficient in the techniques of cinematography, sound engineering, production design, and editing. While in school, he started working professionally as a documentary filmmaker. After graduation he became a cinematographer, working most notably for director Paul Verhoeven (ROBOCOP, STARSHIP TROOPERS) on films such as TURKISH DELIGHT (Turks Fruit, 1973) and KATIE TIPPEL (Keetje Tippel, 1975).

De Bont`s camerawork caught the attention of American film companies. Moving to the US, he eventually became one of the most highly-regarded cinematographers in the business, with credits that included the box office hits THE JEWEL OF THE NILE (1985), DIE HARD (1988), BLACK RAIN (1989), FLATLINERS (1990), THE HUNT FOR RED OCTOBER (1990), LETHAL WEAPON 3 (1992) and BASIC INSTINCT (1992, reuniting with Paul Verhoeven).

Jan De Bont finally got his chance to direct with the Keanu Reeves/Sandra Bullock action movie SPEED (1994). Produced for $37 million, SPEED was both a critical and commercial hit, earning $125 million in the US and another $229 million internationally. De Bont was suddenly in high demand as a director, his name attached to projects like THE DISCIPLE, an Arnold Schwarzenegger thriller in development for Walt Disney`s Caravan Pictures division. But on June 15th -- less than a week after SPEED`s release -- he signed a two year deal with 20th Century Fox, giving the studio the first option on his next film. As part of the Fox agreement, De Bont was expected to direct OVERKILL for Ridley Scott`s Scott Free Productions.1 "It was right after SPEED had come out, so everybody in town wanted him. He was the hot director," observed Chris Lee.2 But despite the Fox deal, De Bont was very interested in GODZILLA... one of the key reasons being that he was an abiding fan of the Toho films. "It’s like some people fall in love with westerns or other things," he told SciFi Japan. "I loved Godzilla movies."

"I first saw the original GODZILLA film in Amsterdam when I was a kid," De Bont recalled. "It`s one of those movies that stick with you."3 But seeing all of the other movies in the series required some effort. "The ones that were shown in the United States were also shown in Holland. There were also some compilations of Godzilla movies, these VHS tapes you could get at the time that were montages of three movies together that were very interesting. But mostly I got them from Japan or from people I knew."

SPEED`s success suddenly gave De Bont the opportunity to do his own Godzilla movie. "I had asked to read the script for many years, because I really loved Godzilla movies as a kid and thought a new version could be really great. Of course, the never wanted to give it to me because they wanted a so-called `A` director. After SPEED came out, all of a sudden they called and asked if I was interested in reading the script and I said, `Yeah, I`ve been interested in reading the script for two years`."4 The director reported that he had "positive feelings about the project" after speaking with Robert Fried.5 He also praised the Ted Elliott/Terry Rossio screenplay, describing it as, "extremely exciting and very well-written. They have an incredible imagination. I read a script of theirs two or three years ago called A PRINCESS OF MARS, which Disney had, and I said to them, `You have to let me direct this movie` because it was such an imaginative script. It was also, unfortunately, very expensive, and Disney said no. Now, of course, they want me to direct that film, but it`s a little late."6

He liked that the GODZILLA screenplay was so different from the other films he was being pitched at that time. "I was being offered a lot of violent scripts. This was a chance to do a fantasy movie, one that makes you feel good at the end."7 He added that, "There`s a good chance the monster will survive."8

The Hollywood Reporter covered the TriStar/Jan De Bont negotiations. From the front page of the June 28, 1994 edition. © 1994 HR Indistries, Inc.

The Hollywood Reporter covered the TriStar/Jan De Bont negotiations. From the front page of the June 28, 1994 edition. © 1994 HR Indistries, Inc.Knowing Jan De Bont`s enthusiasm -- and with the understanding that he would return for a sequel to SPEED -- 20th Century Fox decided to keep the director happy and let him out of his option with the studio so he could make GODZILLA. TriStar and De Bont quickly agreed on a two year/one picture deal that would pay the director $4.2 million plus percentages, a substantial increase from the $150,000 he was paid to direct SPEED. In an interview with The Hollywood Reporter, TriStar president Marc Platt said, "I`m thrilled that Jan has chosen GODZILLA as his next project. His visual style and flair for large-scale action are the perfect match for the film."9 Platt also spoke to Variety, stating, "There`s a worldwide expectation of what an up-to-date version of GODZILLA could be. It`s exciting to combine that with a great new talent like Jan De Bont."10

Cary Woods was equally enthusiastic, declaring, "Jan is one of the great visual stylists in cinema today, and has a real strong feeling for suspense and big action pieces. I think the choice of Jan makes a statement about the kind of movie we want to make. He has not been associated with any action pieces that you would call campy or schlocky, or anything but first-rate."11 Screenwriters Terry Rossio and Ted Elliott were also pleased that De Bont was aboard. "At the time," Rossio recalled, "the inside scoop was that De Bont was responsible for the look and feel of the highly successful John McTiernan movies [DIE HARD, THE HUNT FOR RED OCTOBER], where De Bont worked as his cinematographer. Given McTiernan`s lack of success without De Bont, that may have been the case. We were jazzed."

But the news caught some of the filmmakers who had turned down GODZILLA by surprise. "In Hollywood, when you pass up a project and then a really big director says yes to it, you immediately go, `Ohhh, noooo!` We thought we had really screwed up," Dean Devlin bemoaned.12 "You suddenly go, `Wait a minute, what did he see that we didn`t see? What did we miss?`"13 Unlike his partner, Roland Emmerich was indifferent about the situation. "I always thought, how could we remake that? I had no clue," he remarked. "Then I heard that Jan was doing it and I thought, oh, Jan`s a clever guy, that`s good."14

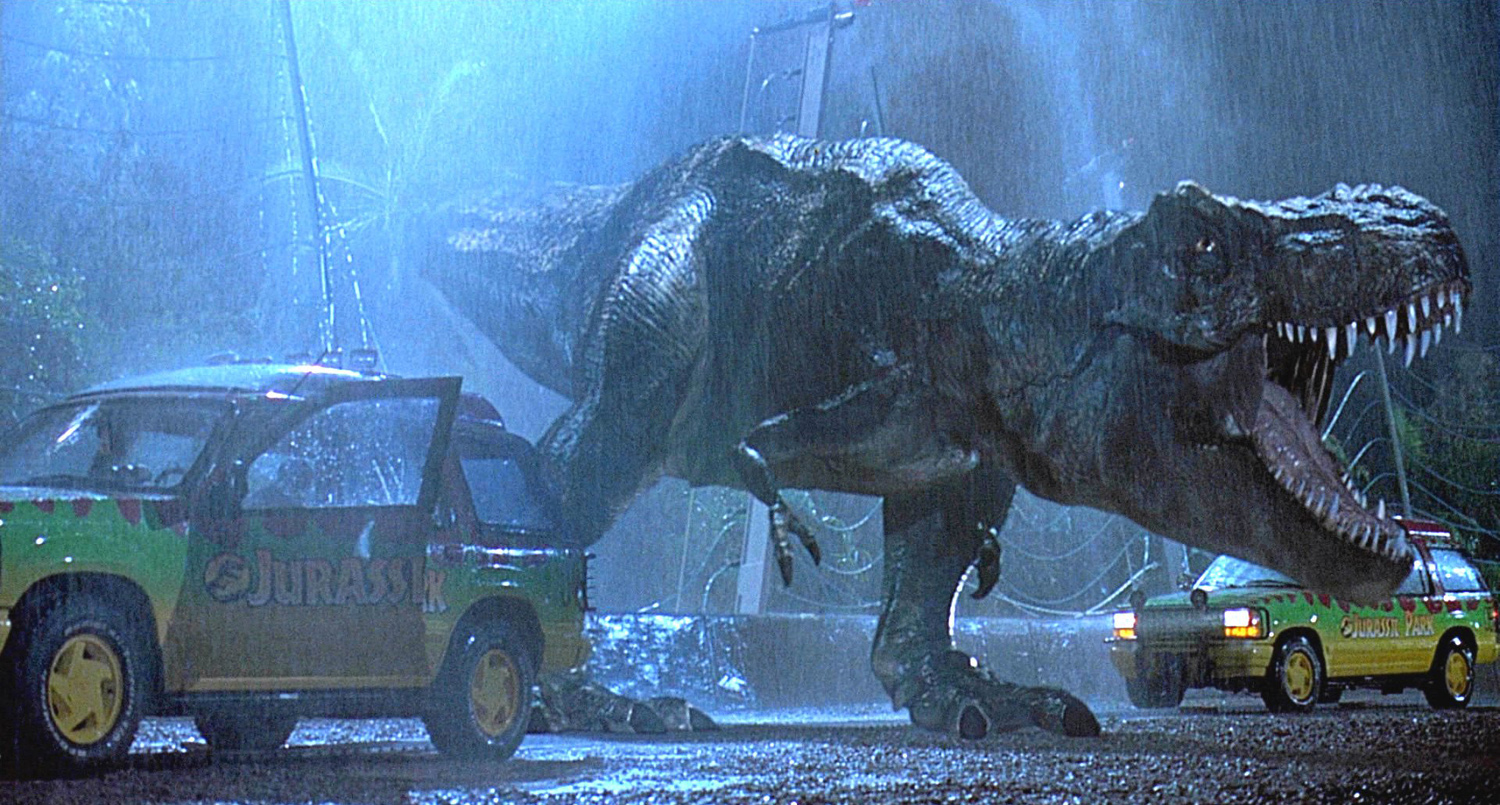

De Bont wanted to bring Godzilla to onscreen life with the realism depicted in JURASSIC PARK. TM & © Universal Studios and Amblin Entertainment

De Bont wanted to bring Godzilla to onscreen life with the realism depicted in JURASSIC PARK. TM & © Universal Studios and Amblin EntertainmentWith the contracts signed, De Bont was eager to make his GODZILLA on a much larger scale than the Toho movies. "They still make those films like that for a couple of million dollars in Japan, and there`s a small crowd that likes it that way," he said in a 1994 interview. "But I think audiences are more sophisticated, and I would like to make Godzilla and his adversary a lot more realistic. I`m not going to make it less funny -- there`s going to be a lot of humor in the movie -- but it must be amazing to see a monster that`s that big, 250 feet tall, that looks real. And when you make it that convincing, you`re going to accept it, like the dinosaurs in JURASSIC PARK. That`s the way we want to do this movie -- to have a real monster."15

But the director still saw Toho`s Godzillas as the true inspiration for his own film, rhapsodizing that, "I liked how they were made. There’s a bad side and a tiny little good side to Godzilla, and you have to show those sides. He was born out of an accident... a horrific situation that brought him to life. So he’s kind of fighting that, as well, and you have to feel that a little bit. And they surrounded him with so many creatures... Mothra, the three-headed Ghidorah... but if you see them together they all make sense."

"And I loved the way that the locations always played such a big part in the Godzilla movies. Destroying Tokyo in the first movie, that was one of the things Godzilla had to do because it was those people who basically created him and it was a little bit of payback. I loved all those parts... it makes me smile when you look at those old movies." He felt the the Elliott/Rossio screenplay, "made it understandable why this film takes place in the United States, which never happened in the other movies. And I thought we’re doing it in the United States and having a reason for him to be here... you can make those amazing available locations that we have here play to our own advantage in the movie. Make those places almost like a worthy opponent for Godzilla to deal with."

No budget had yet been set for GODZILLA, but industry trades rumored that the production would cost between $50 million and $65 million, roughly what had been spent on JURASSIC PARK the year before. "The studio is willing to spend whatever it takes," De Bont told United Press International.16

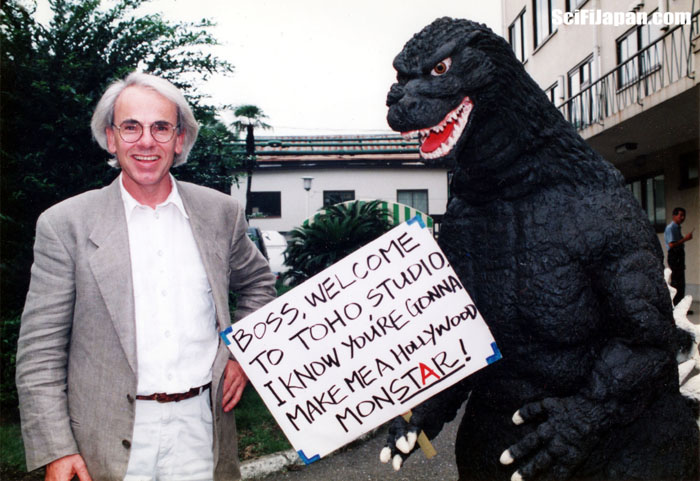

Toho flew Jan De Bont out to Japan for meetings at the studio, where he was greeted by a performer in a Godzilla suit holding a sign that read `I know you`re gonna make me a Hollywood monstar`.17 For the lifelong Godzilla fan the trip was great fun but also a bit of risk... he knew it was vitally important to have Toho`s blessing. "To get the movie made, Toho had to approve it," he explained. "I had to go there because they could say ‘no’ to Sony. And, rightfully, they worried about what would happen to their character. That was their livelihood; they had made over 20 of these movies which were very profitable in their own market. It’s even more amazing that you can make so many movies about one creature and keep drawing so many people watching how the monster destroys their country."

After decades of making Godzilla films in Japan, Toho had questions about how the monster`s size would be portrayed in an American production. © 1984 Toho Co., Ltd.

After decades of making Godzilla films in Japan, Toho had questions about how the monster`s size would be portrayed in an American production. © 1984 Toho Co., Ltd."I went to Toho and we had a big meeting in a gigantic room with the directors and executives and lawyers there. And what they wanted to hear about was why I loved Godzilla. They had some issues with the scale [I wanted for Godzilla]. They didn’t like him to be that big, because when you’re working with men in suits there’s only so big you can with the scale without losing detail in the models. It’s tricky, and they learned that by making those movies and seeing what can go wrong. And I got them on my side by telling them ‘I don’t want to change the character of Godzilla. I want to use CGI for some of the Godzilla effects, but I don’t want to change his size or what he looks like.’ And that’s what made them trust me."

"I spent quite a few days there and met all the people. I met some of the directors. There’s a dedication to the character that you don’t see very often. In the United States it’s just like a job and you do the best you can, but you don’t understand all the meaning that character has for Japan. I met the guy in the suit... he was at the studio when I arrived there... ‘Welcome Jan De Bont. We love that you love Godzilla.’ And it was really all fantastic. And then the lawyers at Sony started screwing it up."

The director had won over Toho, but -- much to his surprise -- he discovered that he now had to do the same with the upper management of Sony Pictures. Even though the studio had licensed Godzilla, the executives who had initially rejected the idea were still squeamish about doing the picture. "The studio was very worried about a movie like that; the Japanese subject matter," De Bont explained. "There were endless meetings. [Executive vice president of production] Amy Pascal was the lead, and I don’t think she understood anything about Godzilla. She kept asking more people to come to the meetings and give their opinions. They always believe that nobody knows anything... they thought that nobody had heard of Godzilla. And they were very worried about that."

"So we wanted to clear the way with a really good script that they basically couldn’t refuse. That’s what we thought, anyway," he said. “I felt Ted and Terry did such a good job on GODZILLA. They came up with a really great script, and that’s when the problems really started.”

Logo for the GODZILLA production company, Gojira Productions, Inc. Image courtesy of Terry Rossio. © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.

Logo for the GODZILLA production company, Gojira Productions, Inc. Image courtesy of Terry Rossio. © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.PRE-PRODUCTION BEGINS

"You need an effects supervisor who is excited and loves to work with new things and new challenges." --GODZILLA (1994) director Jan De Bont

On July 27, 1994, Chris Lee registered Gojira Productions, Inc. as the group that would produce GODZILLA. Jan De Bont and his core staff were assigned Suite 206 in the TriStar Building on the Sony Studios lot in Culver City to begin pre-production for the film.

De Bont said he had very little interaction with Cary Woods or Robert Fried once the work began. "I met with them, of course, but I don’t know what their function was, to be honest. I don’t have any negative feelings about them, but my dealings were mostly with Barrie Osborne. Barrie is an incredible line producer. And ultimately when you make a movie, the line producer’s the only one who is important. The other ones are just paper pushers."

Barrie M. Osborne is an industry veteran, having worked on APOCALYPSE NOW (1979), FACE/OFF (1997), THE MATRIX (1998) and THE LORD OF THE RINGS trilogy, winning an Oscar as producer of the third film, THE RETURN OF THE KING (2003). "He was there all the time on GODZILLA," De Bont stated. "I really liked him, and the crew liked him. He understood what had to be done and in what order. He understood where to simplify things, and he loved what we were trying to do... to see if mixing animatronics and CGI would be beneficial. Would it be good for the movie? Would it even work?"

De Bont started by meeting with Terry Rossio and Ted Elliott -- who had already been doing script revisions for months -- to discuss the story and make his own recommendations. The writers found him a joy to work with. "De Bont was a great interpretive director... clarifying, emphasizing, making changes for momentum, adjustments for the intricacies of production and for budget. We had a great time," remembered Rossio.

"Ted and Terry were amazing," declared De Bont. "They loved talking together about GODZILLA and they understood completely what I was after. They were so pleasant to work with, and everyone was so open. Often it’s a competition between the director and the screenwriters, but the only competition should be the movie. They totally believed in that. And then you start to appreciate each other and you can start to come up with ideas. And they can go ‘Oh, this is great’ or they can go ‘Well, we had this idea’ and you see that their idea was better. There were no camps, and in that regard it was an extremely pleasant experience."

"I really love those guys, and we stayed friends later. And after GODZILLA they made all those big hits. They became much bigger writers and nobody could afford them anymore, almost," he joked. "They have been one of the best writing teams in the United States for decades; I couldn’t praise those guys enough. And who am I to recommend them? They have proven themselves to be so good that they don’t need any recommendation from me."

In assembling a crew for GODZILLA, one of the first people De Bont brought aboard was his frequent collaborator Boyd Shermis, who was tapped to be the visual effects supervisor for the film. "I had done several commercials with Jan over a couple of years," Shermis told SciFi Japan. "He asked me to do SPEED with him. And then as we were doing another round of car commercials, Jan asked me to do GODZILLA."

Shermis began working in the visual effects field in 1985, spending most of his first five years in the business at Apogee Productions, the Van Nuys FX house founded by Oscar winner John Dykstra (STAR WARS, BATMAN FOREVER, SPIDER-MAN, SPIDER-MAN 2). There he worked on commercials; coordinating, producing, supervising and eventually directing visual effects for a number of Clio and Mobius Advertising Award-winning spots. While at Apogee, Boyd Shermis co-directed and supervised several commercials with Jan De Bont. The two worked well together, and De Bont hired Shermis to design and supervise the visual effects for SPEED. Following that film, both De Bont and Shermis returned to making commercials while De Bont began looking into his next movie project. Shermis recalled that he joined TriStar`s GODZILLA, "That same summer... I think in July. Jan and I were doing a package of Dodge car/truck commercials that summer and we started on GODZILLA at that time."

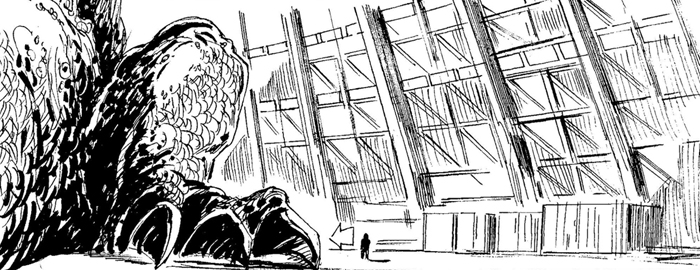

Concept art of the damaged Empire State Building. Image courtesy of Jan De Bont. © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.

Concept art of the damaged Empire State Building. Image courtesy of Jan De Bont. © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.Jan De Bont was pleased that Shermis was eager to experiment with visual effects technology. "Boyd was very intrigued in doing new things. In those days, a lot of effects had to be done with a locked off camera and plate shots, and then you would put your elements in there. No handheld, nothing. But I wanted to shoot with handheld cameras, really super loose, because when you panic you cannot have those constructed shots. I like a very choreographed chaos, but it has to be chaotic when something horrific happens. Nobody has time to step back and say ‘How can we get a nice, beautiful shot here?’. That wouldn’t work."

"And with GODZILLA, things would happen unexpectedly, and I wanted the viewer to be in a position of being able to run away and look around and be afraid by it. If it would all be locked-off shots you would lose some of the emotion of it, some of the drama. Boyd was very open to that. Many supervisors at the time were not able to do that yet; they didn’t think it would work. So you need an effects supervisor who is excited and loves to work with new things and new challenges."

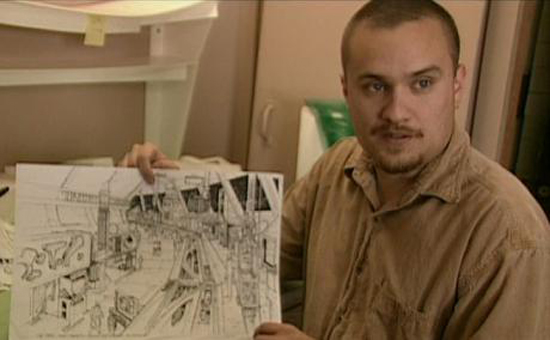

GODZILLA was only Boyd Shermis` second feature film, and as visual effects supervisor he would be in charge of an absolutely mammoth production that would combine live-action footage, digital effects, animatronics and miniatures. So one of his initial tasks was to design the film`s action sequences via previsualization techniques, which in 1994 would primarily entail drawn storyboards rather than computer animatics.

Shermis also had to do a breakdown of the visual effects scenes and figure out which techniques would work best for a given shot, and from there determine the necessary budget for the effects; an amount Jan De Bont could realistically work with and that TriStar would approve. The sheer amount of FX required meant that Shermis would have to hire several different companies and split the work between them depending on their skills and resources. "We needed to break the movie up into several different pieces so that each vendor would not have been overwhelmed," he explained. An additional benefit would be reduced costs, as Shermis and De Bont would be able to choose from FX companies bidding for assignments on GODZILLA.

Once companies were signed for the film, Shermis would then guide and oversee all of the teams from start to completion. He would also need to supervise on-set the filming of scenes involving effects, and later work with the movie`s editor on those scenes.

Another key early addition to the GODZILLA crew was production designer Joseph Nemec III. Unlike Boyd Shermis, Nemec had not worked with Jan De Bont before. But he had a long list of television and film credits, starting as an assistant art director and art director on titles such as V (1983), THE GOONIES (1985), THE COLOR PURPLE (1985), ALIEN NATION (1988) and THE ABYSS (1989). Leading up to GODZILLA, Nemec had been production designer on number of large scale productions, including TERMINATOR 2: JUDGMENT DAY, PATRIOT GAMES (1992) and THE SHADOW (1994). After GODZILLA, Nemec would work again with De Bont on TWISTER and SPEED 2: CRUISE CONTROL. More recent credits include the remake of THE HILLS HAVE EYES (2006), A PERFECT GETAWAY (2009), the Jason Statham action film SAFE (2012) and RIDDICK (2013), the latest film in the CHRONICLES OF RIDDICK series.

Joseph Nemec told SciFi Japan that he joined GODZILLA, "I believe it was in the autumn of 1994. I got the assignment through a traditional interview process." His role was to help select and work with the artists who would create concept art for the monsters, and also personally design many of the sets and locations to be seen in the film.

"Joe knew not to make things too pretty," said Jan De Bont. "Unfortunately, when we see destruction it’s always photographed to look pretty. I don’t know why people do that. Destruction is not pretty, definitely not for the people whose property it is, whose valuables or family is in there. Don’t make it pretty; make it as real as possible. It should be chaos, not perfectly designed destruction. The realness of it is what makes a film special."

Concept art of the Japanese fishing village by Joseph Nemec. Illustration courtesy of the artist. © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.

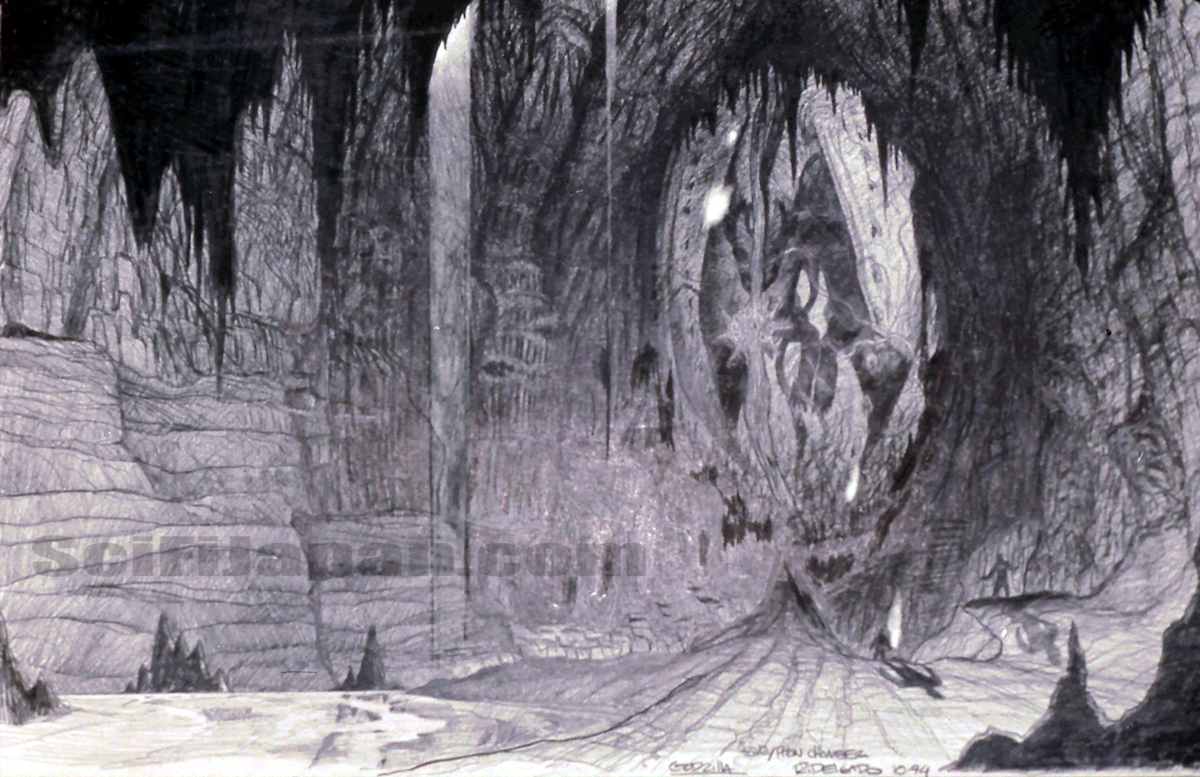

Concept art of the Japanese fishing village by Joseph Nemec. Illustration courtesy of the artist. © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.Nemec disclosed that, during his time on the film, "Both Godzilla and the Gryphon were designed, along with the Japanese fishing village, the ice cave where Godzilla re-appeared from, and some of the military spaces."

Among the locations Nemec personally worked on was the Japanese fishing village, which briefly appears in the screenplay when Godzilla comes ashore during a storm. Jan De Bont was particularly fond of that scene, describing it as "a little bit in Japan, a very small visit to [Godzilla`s] motherland."1 He intended to make it the first scene he would shoot for the film.

"The fishing village sets were to be built in Brookings, Oregon," Nemec recalled. "In addition, there had been location scouting in Alaska for the snow/ice caverns and under glacial rivers, and some scouting done in Utah and Arizona." Jan De Bont said that Nemec and his team were very efficient. He recounted that, by the time GODZILLA was canceled, "we had all the sets designed, we had models made of the sets, we had a whole gigantic room filled with miniature sets. It looked extremely impressive. We scouted all the locations, we got permissions for all the locations, and that’s pretty far along in movie terms."

Variety reported that the filming of GODZILLA was now set to begin in November 1994.

Model of the ice cavern where Godzilla is discovered in hibernation. Photos courtesy of Jan De Bont. © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.

Model of the ice cavern where Godzilla is discovered in hibernation. Photos courtesy of Jan De Bont. © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd. Preliminary Godzilla concept design by Ricardo Delgado. © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.

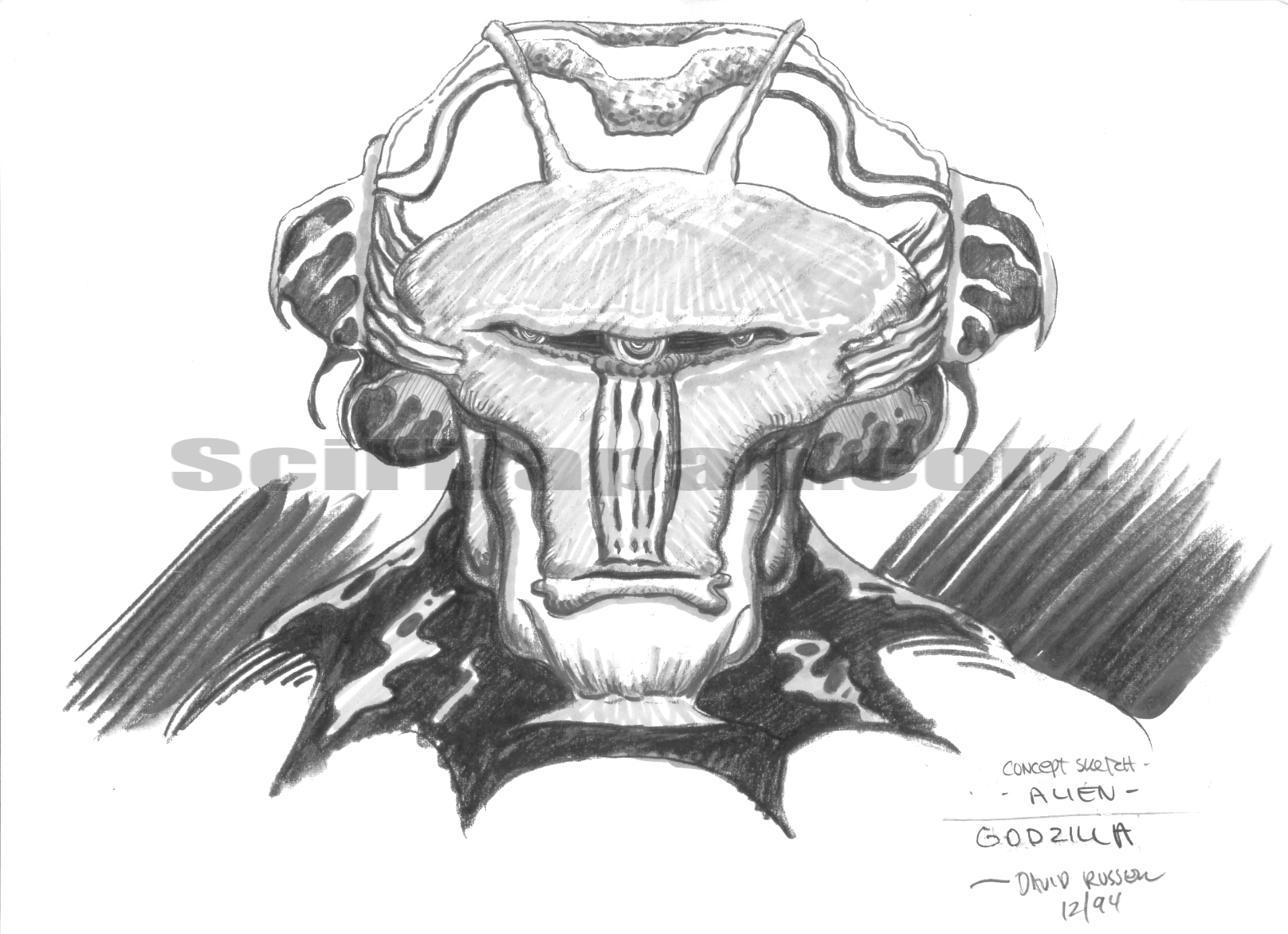

Preliminary Godzilla concept design by Ricardo Delgado. © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.CONCEPTUAL DESIGN, ROUND ONE: GOJIRA PRODUCTIONS and STAN WINSTON

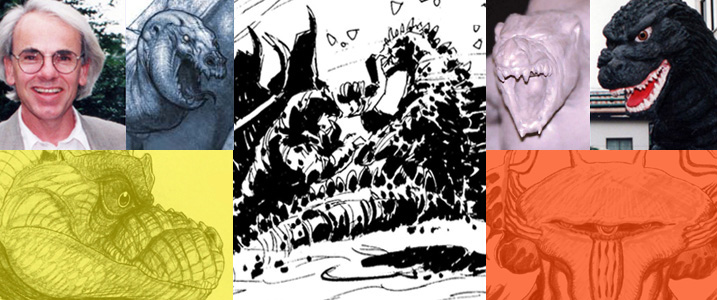

"It would have been the first time that Godzilla was reimagined so that was really exciting for us." --Stan Winston Studio Godzilla designer Mark “Crash” McCreery

"If it ain’t broke, why fix it?" --GODZILLA (1994) concept artist Ricardo Delgado

Shortly after signing the deal to direct GODZILLA, Jan De Bont met with Stan Winston, the four-time Academy Award-winning FX artist whose Stan Winston Studio had designed and built the full scale dinosaurs for Steven Spielberg`s JURASSIC PARK. Joseph Nemec recalled that Winston`s pitch to do GODZILLA`s creature effects came at the very start of pre-production, saying, "Stan was already involved when I came on board."

"He was already involved then, and that had to do with what could be created with animatronics," De Bont revealed.

Stan Winston (bottom center) with his full-scale mechanical Tyrannosaurus rex on the set of JURASSIC PARK. TM & © Universal Studios and Amblin Entertainment

Stan Winston (bottom center) with his full-scale mechanical Tyrannosaurus rex on the set of JURASSIC PARK. TM & © Universal Studios and Amblin EntertainmentDuring a November 1994 interview for Movieline, Winston recalled his inspirations for becoming an FX artist: “As a kid, I couldn’t wait to see movies like THE CREATURE FROM THE BLACK LAGOON and THE WIZARD OF OZ. Watching men dressed up in big rubber suits, like in GODZILLA, was fun but they weren’t convincing to me. They were too strapped by a lack of artistic and technical ability to really create live, believable monsters. The stop-motion movies, the ones where we could see real dinosaurs and real characters, like KING KONG and THE BEAST FROM 20,000 FATHOMS, were my favorites. But, in my innocent mind, I always thought, ‘Gosh, wouldn’t it be nice not to know it was animation? For this to be really real?’ Those are the things that pushed me in the direction that I eventually went in.”1

Winston`s skill at creating realistic creatures was on full display in JURASSIC PARK. He first became involved with the project in December 1990, as Universal Pictures was growing increasingly concerned that the cost of doing the life-sized dinosaur effects required by the story would make the film financially unfeasible. But Winston felt the dinosaurs could be done with animatronics... and he wanted to be the one to do it. He assigned one of his studio`s top conceptual artists, Mark “Crash” McCreery, to draw a number of detailed sketches of the dinosaurs featured in the original novel. "We didn`t have a contract, we didn`t have a job," Winston acknowledged. "There were constant rumors that JURASSIC PARK was not going to get made or that Steven had decided not to do it. Through it all, we just kept plodding forward, hoping to make the picture happen for both us and the studio."2

Crash McCreery proved to be the right choice. A lifelong dinosaur enthusiast, McCreery went to work for Stan Winston after graduating from the Art Center College of Design in Pasadena in 1988. He quickly established himself as one of the best concept artists in the business with credits that include PREDATOR 2 (1990), modifying Tim Burton`s sketches into the final design for EDWARD SCISSORHANDS (1990), James Cameron`s TERMINATOR 2: JUDGMENT DAY and the Penguin for Burton`s BATMAN RETURNS (1992). His artwork for JURASSIC PARK -- depicting the animals looking and acting according to modern paleontological theory -- highly impressed Universal. The combination of the designs and Stan Winston`s insistence that he could create effective (and affordable) full scale animatronic dinosaurs helped convince Universal to green light the film.

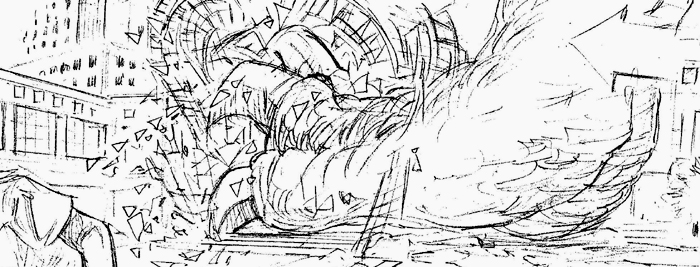

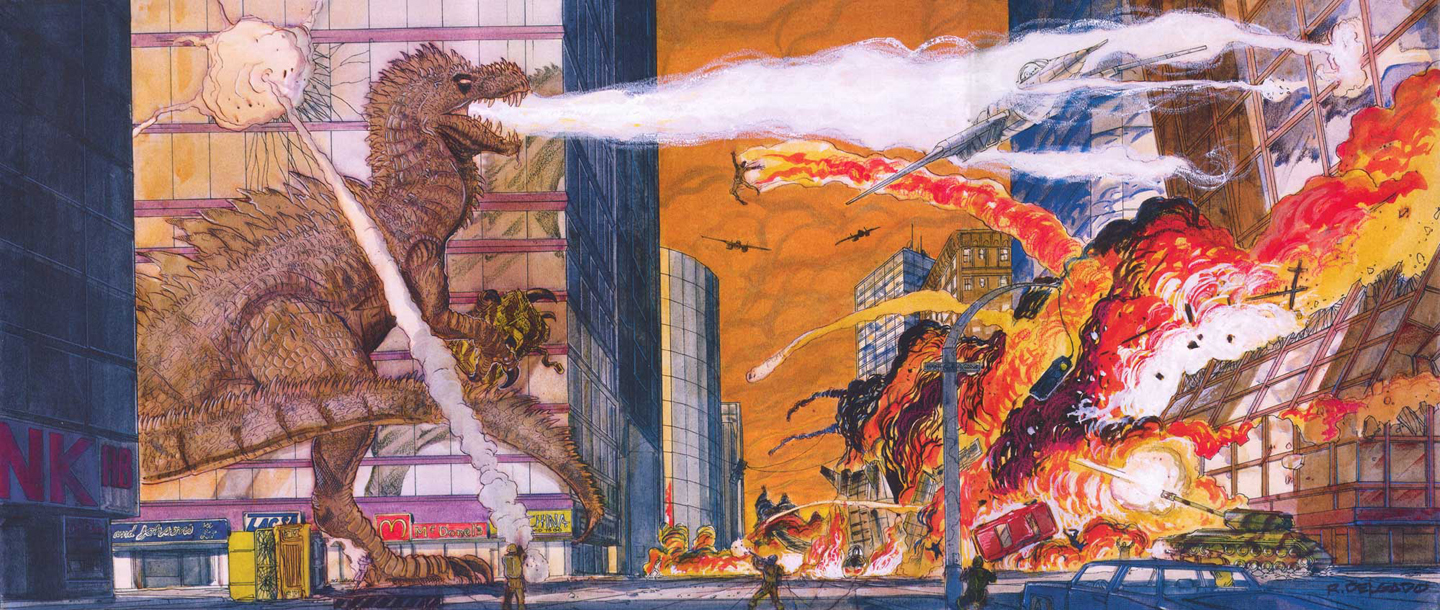

Godzilla battles F-16 fighter jets in early concept art by Winston Studio artist Mark “Crash” McCreery. Image courtesy of Mark McCreery and Stan Winston School of Character Arts. © Stan Winston Studio © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.

Godzilla battles F-16 fighter jets in early concept art by Winston Studio artist Mark “Crash” McCreery. Image courtesy of Mark McCreery and Stan Winston School of Character Arts. © Stan Winston Studio © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.Stan Winston Studio was now hoping to repeat that successful formula with GODZILLA, and had once again turned to Crash McCreery to do the studio`s first take on the monster. "It would have been the first time that Godzilla was reimagined, I think, so that was really exciting for us," McCreery told SciFi Japan.

"We did our part to try to get that show. We really did," said Joey Orosco, a lead character designer for Winston. "Stan wanted it so bad, we wanted it so bad. Crash did this beautiful, beautiful drawing of Godzilla shooting fire out... it was a really cool rendering he did."

"One of my strong points in working with Stan was creating artwork that captured the essence of what they were hopefully looking for as far as the tone and attitudes towards the film," recounted McCreery, explaining that his initial approach to Godzilla was, "not unlike what I had done for JURASSIC PARK. One of the first pieces I had done sold Steven Spielberg and Universal on having Stan and his guys design the dinosaurs. The anatomy wasn’t really there, the detail wasn’t really there, but it kind of captured an action and a tone. And the first drawing that I did for GODZILLA was kind of like that. It depicted Godzilla in a pose that was not reminiscent of the original at all; it was much more animated and animal-like and less human. It depicted some jets flying in and used under lighting which I always thought was classic Godzilla, him being so huge the lighting was always coming from underneath. So I retained as much of the classic look of Godzilla as I could, but I added some of my own -- especially after working on JURASSIC PARK -- dinosaur and character qualities."

Stan Winston presented McCreery`s artwork to a very impressed De Bont. "Crash... talk about artists! If you look at his archive, it deserves museum shows," raved the director. Winston didn`t yet have the GODZILLA contract, but that didn`t mean the sample work was provided at no charge. Asked if the concept art would have done solely on spec, Winston Studio artist Bruce Spaulding Fuller replied, "That`s highly unlikely. The artwork generated may have been part of trying to coax more money out of the studio -- but don`t hold me to that. I don`t know really, but I`m sure Stan got paid."

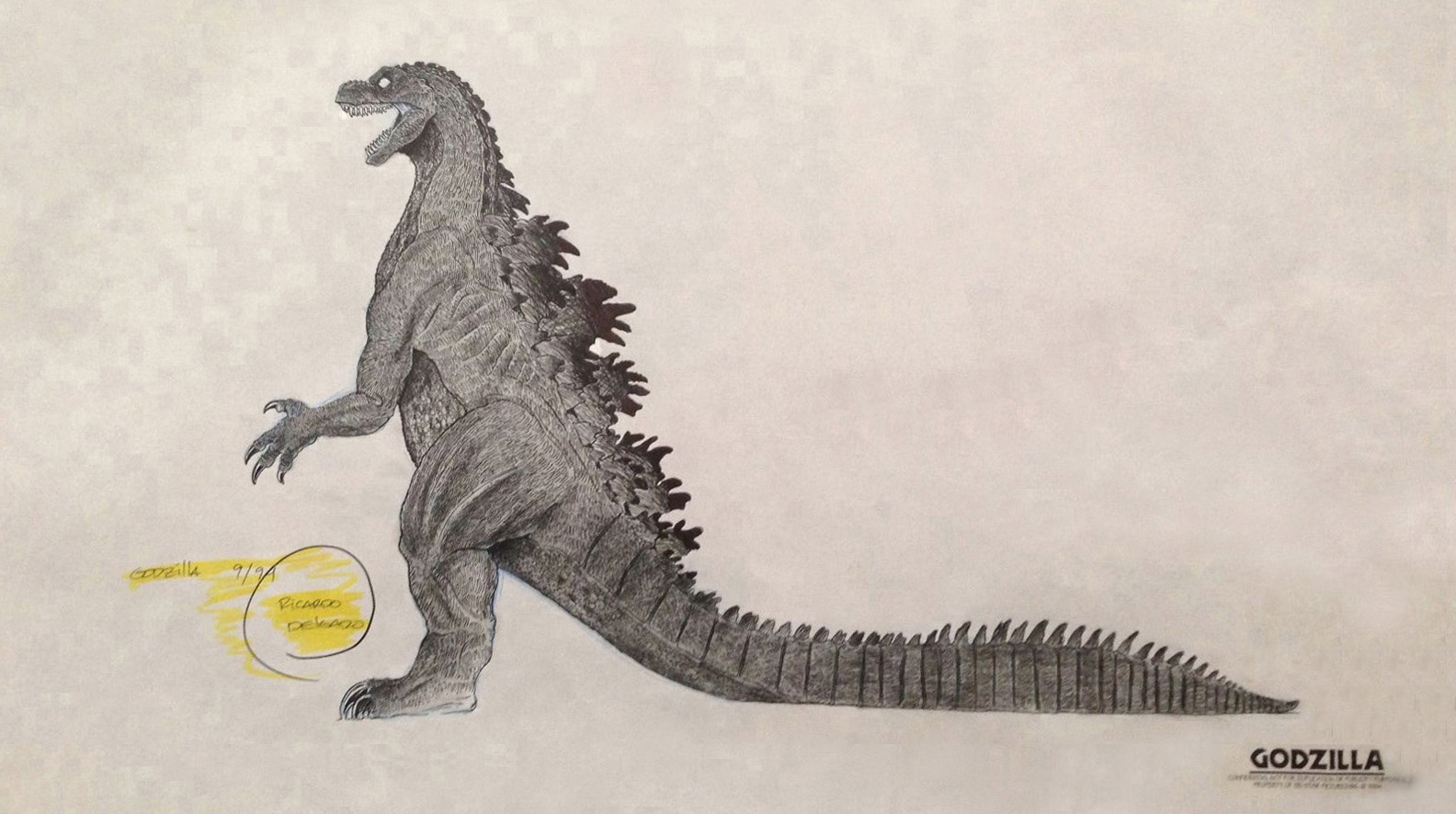

While Winston Studio worked on their pitch, Jan De Bont and his crew selected a handful of artists to work in-house at the GODZILLA production offices, crafting some early concept art and storyboards. One of their first hires was Ricardo Delgado who, like Mark McCreery, was both a graduate of the Art Center College of Design and a dinosaur buff. In 1993, Delgado created the Dark Horse Comics mini-series Age of Reptiles which won Eisner Awards (the comic book industry`s equivalent of the Oscar) for Best Limited Series and Talent Deserving of Wider Recognition. He had also worked as a production illustrator and storyboard artist for the television series STAR TREK: DEEP SPACE NINE (1993) and SEAQUEST 2032 (1993) and the feature films BEVERLY HILLS COP III (1994) and TRUE LIES (1994).

"I got into this project based a lot on my dinosaur comic, Age of Reptiles,” Ricardo Delgado explained. "I saw an article in The Hollywood Reporter that Jan was going to direct the movie and I had once interviewed with Jan to do storyboards for SPEED. So I called his office, told them that I had done a dinosaur comic and faxed over some samples. Subsequently, I was invited to come to his production company, Blue Tulip Productions, on the Fox lot. I believe I interviewed with Joe Nemec, but Jan was there, too.”

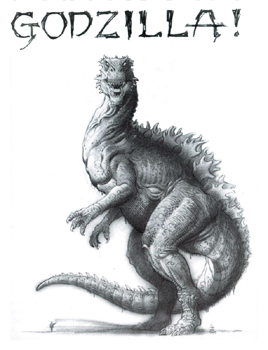

Even before the job interview, Delgado had some strong ideas on how to approach the character of Godzilla. "I had just been so impressed with the Tyrannosaur in JURASSIC PARK -- in all the dinosaurs in that film -- and it was one of those things where I really felt that Godzilla needed that modern, textural interpretation of what a creature that size would be like in reality. But it wasn’t just taking advantage of the new technology... I really wanted to create that character because I’m a big fan of Godzilla. I watched all the films when I was a kid."

“I prepared for the interview by doing a few Godzilla doodles of my own. One pencil rendering was my version of the monster... that was one of the pieces I first showed to Jan. And then I had a second, color piece featuring a Godzilla-like monster in a city. Those were done out of my enthusiasm for the subject matter -- I wouldn’t have done that for many other shows but a project like GODZILLA or CREATURE FROM THE BLACK LAGOON would have inspired me."

Sample illustration done by Ricardo Delgado for his GODZILLA job interview. This early depiction of the creature mixed features from the Toho Godzilla and the titular monster from Ray Harryhausen`s THE BEAST FROM 20,000 FATHOMS. Image courtesy of the artist. © 1994 Ricardo Delgado

Sample illustration done by Ricardo Delgado for his GODZILLA job interview. This early depiction of the creature mixed features from the Toho Godzilla and the titular monster from Ray Harryhausen`s THE BEAST FROM 20,000 FATHOMS. Image courtesy of the artist. © 1994 Ricardo Delgado“I showed Jan the various Godzilla drawings I had done and I also showed him my comics. And that made him and Joe Nemec feel that I’m ‘the reptile guy’ -- that I can handle that sort of thing. They seemed to like that, and a couple of weeks later I got a call to come work on the film."

"I felt really flattered to get an assignment like GODZILLA so quickly in my career," Delgado asserted. "GODZILLA might have been my fourth or fifth film; I was still pretty young. I graduated in 1989 and five years later I was working on this film. That’s a pretty quick rise for a concept artist. It was really cool, and it was my honor and my pleasure to get on it and work with everyone. And when I showed up for work the first day, my friend Carlos Huante was there. He’d been hired by Joe to design the Gryphon."

An extremely talented illustrator and sculptor, Carlos Huante was yet another former student of Pasadena`s Art Center College of Design, where he attended night classes in life drawing. He began work as a layout artist for the animation studios Filmation Associates and Ruby-Spears Productions, finding his niche as a character designer for the GHOSTBUSTERS cartoon series. After working in animation for eight years, Huante transitioned to live action films, creating concept art and character designs for such films as BATMAN FOREVER (1995), MEN IN BLACK (1997), DEEP RISING (1998), MIGHTY JOE YOUNG (1998), THE MUMMY (1999), MEN IN BLACK II (2002), SIGNS (2002), HELLBOY (2004), BLADE: TRINITY (2004), WAR OF THE WORLDS (2005), X-MEN: THE LAST STAND (2006) and PROMETHEUS (2012). Carlos also spent several years in the creature design department at Lucas Digital.

Huante recalled how he got the assignment to work on GODZILLA: "Film artists were a tight knit group back then. A friend of mine called while I was working on BATMAN FOREVER to tell me that they were starting to look for a crew for GODZILLA. That`s what we would all do; we would call the guys we knew would be best for a certain job." He confirmed that he did not produce any concept art of Godzilla, stating, "I was hired specifically to design the Gryphon and Probe Bats."

"They were great guys," said Jan De Bont. "Ricardo was a BIG Godzilla fan. We were lucky that we had a team that all liked Godzilla, or came to like it."

Ricardo Delgado`s final concept design for Godzilla maintained the traditional look of the monster, mixed with a more realistic dinosaurian anatomy. Image courtesy of Ricardo Delgado. © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.

Ricardo Delgado`s final concept design for Godzilla maintained the traditional look of the monster, mixed with a more realistic dinosaurian anatomy. Image courtesy of Ricardo Delgado. © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.In August 1994, the artists went to work with De Bont and Joseph Nemec at Gojira Productions on the Sony Studios lot. "We were originally in an office near the main entrance, and later moved to the middle of the lot," Ricardo Delgado recalled. Carlos Huante remembered that, at the start, "Ricardo and myself were the only two artists there," though the art department would soon expand to include a storyboard crew.

Lighthearted illustration of Godzilla sneaking up on some unsuspecting dog walkers. Image courtesy of Jan De Bont. © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.

Lighthearted illustration of Godzilla sneaking up on some unsuspecting dog walkers. Image courtesy of Jan De Bont. © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.Huante and Delgado were aware that Winston Studio was vying to create the monsters for GODZILLA. "We knew that Stan Winston was involved early on enough to have Crash McCreery generate a couple of images, but we were told to do our versions of the creatures," recounted Delgado. "Crash had done two drawings that I can think of. One was a profile that was similar to the maquette done at Winston later on in the year, and one was a drawing where Godzilla is fighting and there’s a jet flying in the foreground. Those were before, or maybe concurrent to what we were doing... I think it’s completely possible that we were both working at the same time. We were working for Joe and Jan, and Stan was approaching the design process as well. But I remember vividly -- if not accurately -- Jan showing me the two Crash drawings during my interview. The drawings that were generated were probably in hopes of getting the bid. If Stan had gotten the bid that early then I don’t think Carlos and I even would have been hired."

As the production designer, it was Joe Nemec’s task to work closely with the artists while Jan De Bont handled other aspects of GODZILLA’s pre-production. Looking back, Carlos Huante maintained, "We would meet with Jan every once in a while... but thinking about it now, it wasn`t often enough." Ricardo Delgado remembered that, "I dealt mostly on the show with Joe Nemec, but Jan would come in to see what I was doing when I was working on the GODZILLA stuff. I would just stand there, and he and Joe Nemec would talk about the design.”

Godzilla facial expressions by Delgado, featuring an earlier concept that more closely resembled a theropod dinosaur than Toho`s monster. Image courtesy of Jan De Bont. © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.

Godzilla facial expressions by Delgado, featuring an earlier concept that more closely resembled a theropod dinosaur than Toho`s monster. Image courtesy of Jan De Bont. © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.Delgado felt the artists were in good hands with Nemec. "Joe, to his credit, was very supportive. There were a few early drawings that I did more in the vein of crossing Godzilla with THE BEAST FROM 20,000 FATHOMS because that’s kind of a fluid connection for me; it was natural to mix them together a little bit. The early ones felt more reptilian... I think I went through a few different drawings that felt very much like a dinosaur or the Beast with Godzilla fins stuck on the back. And Joe said, ‘That’s cool, but let’s push it a little more towards the Godzilla aspect of it’.”

Jeff Farley, who had worked on a maquette of Godzilla for Sony Imageworks, related the importance of staying close to the classic design. "I feel that came from Jan De Bont`s love of Godzilla. From my understanding, he is a true fan," he said.

De Bont confirmed this, insisting, "You have to give the team you’re with a good idea of the design and what it will ultimately have to look like. Then they can start working on all the details. It takes time but it totally pays off."

Delgado felt that an American Godzilla should resemble Toho`s version, unlike the design created by artist William Stout for the unmade 1983 film GODZILLA, KING OF THE MONSTERS IN 3-D. © 1983 Toho Co., Ltd.

Delgado felt that an American Godzilla should resemble Toho`s version, unlike the design created by artist William Stout for the unmade 1983 film GODZILLA, KING OF THE MONSTERS IN 3-D. © 1983 Toho Co., Ltd.Following Nemec’s direction, Delgado went for more of a traditional look for Godzilla. Much of his inspiration came from the Godzilla designs Toho had been using in their most recent films at that time. "I had plenty of my own reference material because I was such a fan,” Delgado disclosed. “I had Japanese Godzilla books and magazines that I looked at. I had a few of the Godzilla model kits made by Kaiyodo and Billiken, and those models from the early 90s were very helpful when I was designing the creature’s face.”

“I also looked at some of stuff that Arthur Adams had done [for the Dark Horse Godzilla comic books]. And I looked at what Bill Stout had done for his version of Godzilla [illustrations for the unmade 1983 American production GODZILLA, KING OF THE MONSTERS IN 3-D], but I felt what Bill had done was too dinosaurian. With all due respect to Bill -- he’s one of my influences -- his was more 50/50 dinosaur/Godzilla and I really felt it needed to be more on the Godzilla side with a few accoutrements to sort of streamline it and `dinosaurize` it. And that was a tough line for me to cross... knowing what everyone had done before and what had been realized before."

"To me, some of the Japanese creature designs were based on calligraphic stuff I’ve seen of animals. For example, in KING KONG ESCAPES, the Toho version of King Kong is almost based on the way calligraphy is done for apes or demons. That’s how I felt Godzilla was depicted a little bit, with some of the facial stuff around the cheeks and toward the snout, and the way the snout was separated into three pieces in front of the nose and on each side of the cheek. So I was really careful in analyzing that, and very reverential. I really respected the Toho design."

"Taking my ego out of it, I really wanted this Godzilla to be a combination of my meager contribution and Toho’s Godzilla. If it ain’t broke, why fix it?," Delgado asserted. "If anything, I felt it needed less of whatever I put into it and more of what was already there. I wanted to make it like 80% of what we were familiar with and then 20% new so that the audience would go ‘Oh wow, that’s kinda’ cool.’ It’s different enough where’s it’s still the same thing, essentially."

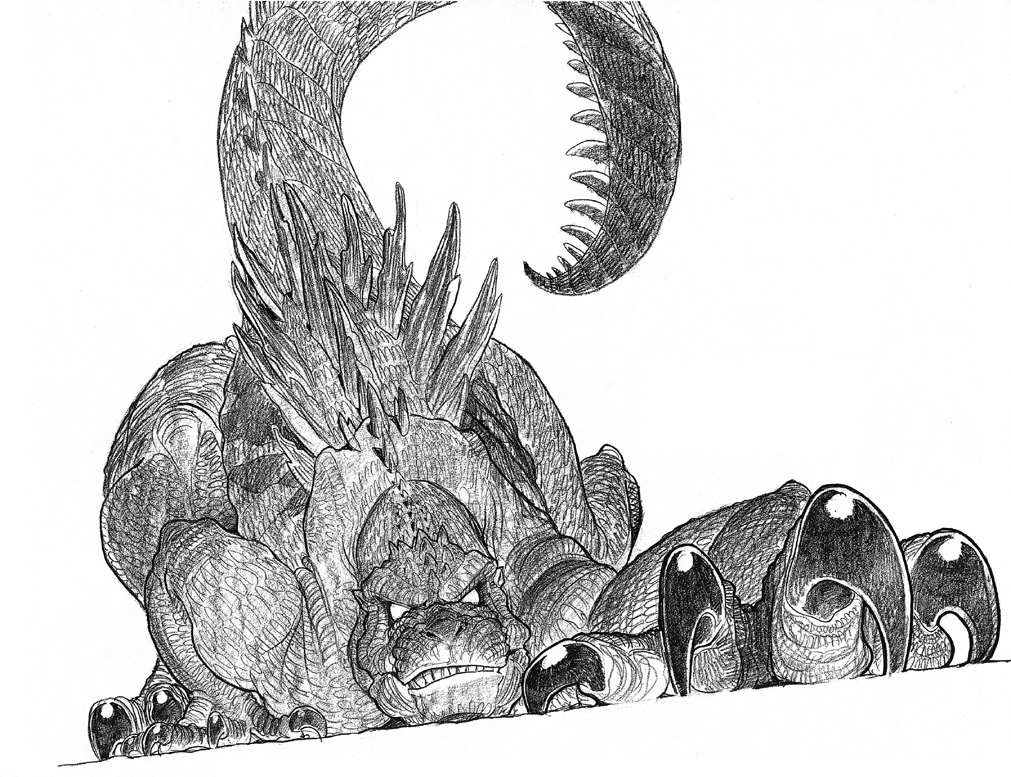

Godzilla crouching in a catlike fashion, as suggested by the film`s script. Image courtesy of Ricardo Delgado. © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/Toho Co., Ltd.

Godzilla crouching in a catlike fashion, as suggested by the film`s script. Image courtesy of Ricardo Delgado. © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/Toho Co., Ltd.Ricardo Delgado finalized his Godzilla design in a trio of sketches drawn in September, 1994. "And out of that comes the drawings that everyone kind of remembers; the crouching Godzilla with the tail whipping around, the portrait drawing, and the crawling drawing. Those are the ones that everyone seems to point to, either with approval or disgust," he laughed.

"I really didn’t want to change a lot about Godzilla; there’s a few design elements that feel a little different. It had the ponderousness and muscularity of Godzilla but I didn’t want the ‘thunder thighs’ Godzilla [of the recent Toho films]; I felt it still needed to make biological sense without really beefing up the legs too much. There’s a paddle of a tail that feels a little more crocodilian. But the head, the torso... perhaps it’s a little thinner, more muscular than the traditional Godzilla, but if you look at it in silhouette you’d go ‘That’s Godzilla’. You really need to look at the curve of the head, and the way it holds its arms in front of its chest, and the way the spines go back gracefully. And ultimately I really felt that, in those last three sketches, that it all came together to make it feel like Godzilla. I wanted to hit a home run with my design and say ‘That’s the Toho Godzilla with a dash of dinosaur put into it’. And that’s really all that it needed to be."

Delgado has fond memories of when Jan De Bont and Joe Nemec came to see the Godzilla designs. "Jan asked ‘You like this?’ and Joe didn’t say anything... he just got this happy look on his face and nodded gleefully. So that kind of cemented this version of the creature."

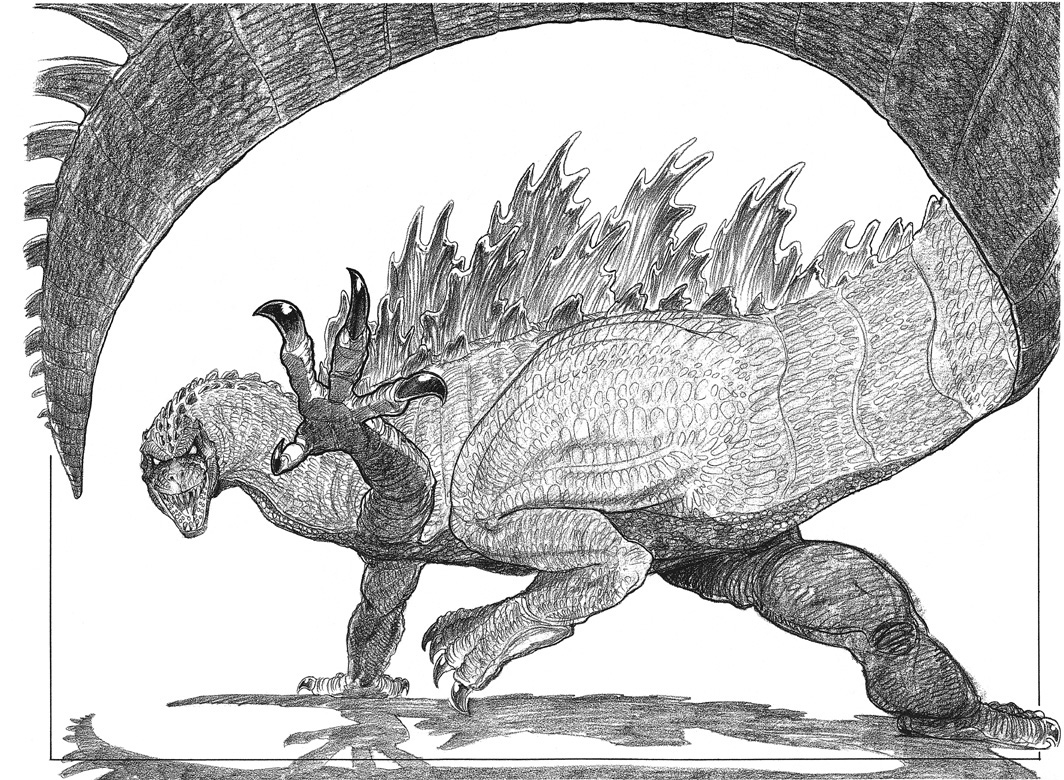

Delgado envisioned a Godzilla that would generally move like the classic Toho character, but was capable of sudden bursts of speed when needed. Image courtesy of the artist. © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/Toho Co., Ltd.

Delgado envisioned a Godzilla that would generally move like the classic Toho character, but was capable of sudden bursts of speed when needed. Image courtesy of the artist. © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/Toho Co., Ltd.Terry Rossio also remembered visiting the GODZILLA art department and being very impressed by the creature designs. "I recall one illustration -- I would love to have this! -- of Godzilla swimming underwater, it was just stunning!," he declared. "Godzilla looked like Godzilla, but with a dynamic pose and sense of movement we had never seen before."

Ricardo Delgado’s take on Godzilla reflected how the monster would move onscreen. The artist felt the JURASSIC PARK T-rex had convincingly portrayed both mass and speed, and envisioned the new Godzilla moving in a similar manner. "That was the goal,” he said. “That you would feel its weight moving around, but when it had to move for the story it could actually move very quickly. A lot of modern reptiles -- like Komodo dragons and crocodiles -- they look like they’re really slow and ponderous creatures but if they want to come and get you they’re going to come and get you. They’re capable of sudden bursts of speed."

"And that was one of the surprises that I was hoping would be part of the story... that in every way, shape and form he would be the Godzilla from the original films in the way he moved, but he would be capable of these quick bursts of speed. It would walk like a traditional Godzilla, he would lumber a lot, but then Godzilla would surprise you with this ability. And when it had to run forward -- and that’s how I drew it, running forward -- the tail would come up. But otherwise, its tail would drag just like the Godzilla we saw in our childhoods.” But Delgado did note one major change in Godzilla’s method of locomotion, which was introduced in the Ted Elliott/Terry Rossio screenplay. “He would be able to crawl around on all fours if he needed to."

In regards to visualizing other famous apects of Godzilla such as the monster’s radioactive breath, Delgado stated, "That was more of a visual effects discussion. I was there to do one thing: design the critter. And they seemed to like what I did, so it was a good time all around."

Most importantly, Delgado felt both his Godzilla design and the film`s screenplay were faithful to what had gone before. “I was always really impressed by the original film, even today I still think that’s one of the best monster movies ever made," he said. "And when I saw the Japanese cut of GODZILLA without the Raymond Burr stuff it made it even tighter, a more relentless film. It has an impressive story and it doesn’t back away from the idea of cause and effect, and you really get the sense of tragedy. There’s that scene where Godzilla is approaching and the mom is telling her kids that they’re going to see their dad soon... there`s the implication that the dad died in the war. It all felt very, very tragic."

"Godzilla is not evil, but is a complete force of nature mixed with a bunch of psychological underpinnings I thought worked well. I thought that tone was fantastic and was hoping some of that would be worked into the film we were working on... that in the story we were trying to tell it would be both scenarios. In the first part of the film, Godzilla is this force of nature and you see him causing much destruction. But in the second part of the film he would form this sort of anti-hero persona and do battle in New York with the Gryphon. It’s very clear that Godzilla is a psychological underpinning for a lot of people in the story. And in the second half, they go ‘Why don’t we unleash our id, essentially, on this alien creature?’ And that’s exactly what they did."

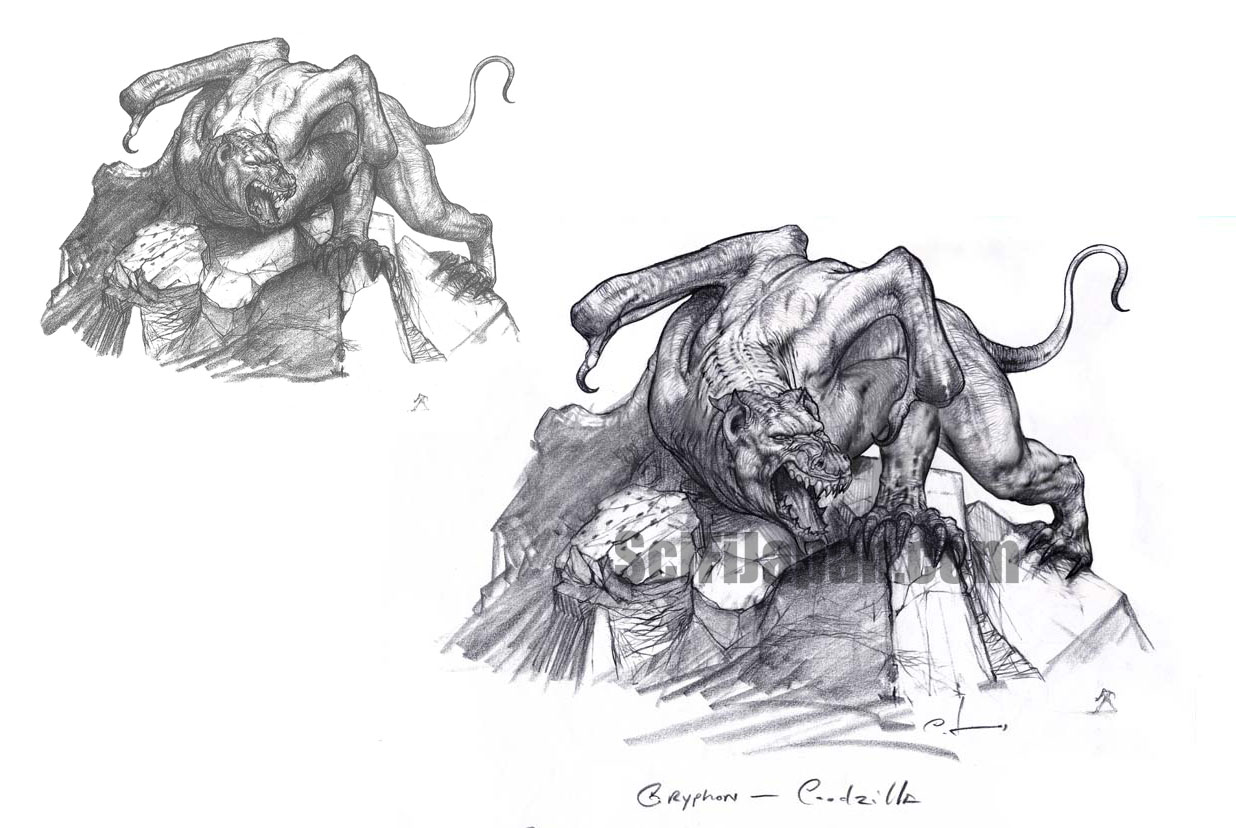

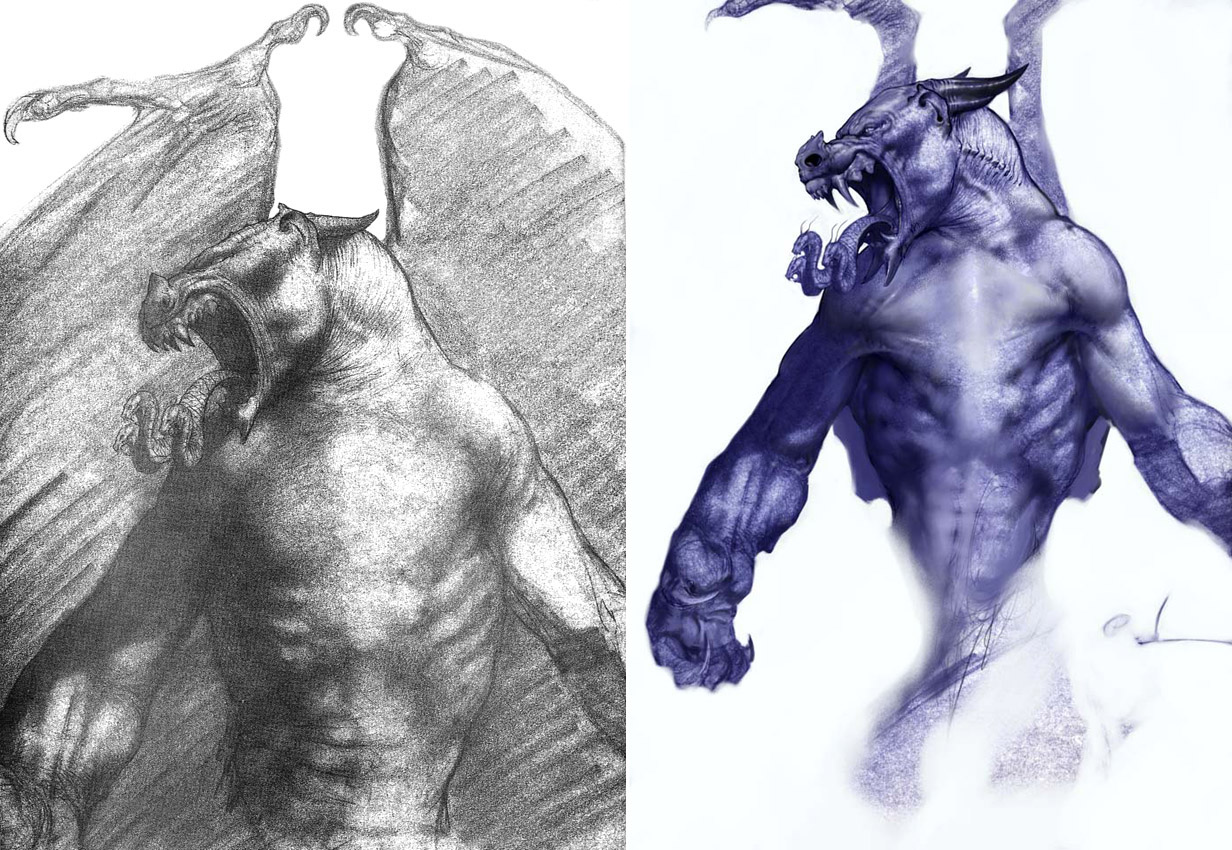

The Gryphon as depicted by conceptual artist Carlos Huante. Image courtesy of Carlos Huante. © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.

The Gryphon as depicted by conceptual artist Carlos Huante. Image courtesy of Carlos Huante. © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.For Jan De Bont, the Gryphon as Godzilla`s enemy was an essential part of the film he wanted to make. "You have to have a second monster because Godzilla can`t be the bad guy," he insisted. "Godzilla in itself means nothing if there isn’t an opponent that threatens him."

Ricardo Delgado thought that, at one point, Godzilla`s intended opponent would have been a face -- or faces -- very familiar to Toho fans. "I’d heard rumors that the Gryphon was supposed to be Ghidorah, but I work in an industry of scuttlebutt and gossip so for a lot of it I just shrug my shoulders."

An alternate take on the Gryphon by Carlos Huante. Image courtesy of the artist. © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.

An alternate take on the Gryphon by Carlos Huante. Image courtesy of the artist. © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.Terry Rossio confirmed that was indeed his and Elliott`s intent. "We originally wanted to have Godzilla fight King Ghidorah," he said, but Toho`s popular three-headed space monster was off-limits.3 Ted Elliott provided additional details. "It turned out that our contract specifically stated that we could use any monsters from the Godzilla family of monsters except Rodan, Mothra, or King Ghidorah. I`m sure Toho believes they can license those individually, so they didn`t include them in the Godzilla license," he revealed. "We were left coming up with our own guy. Let`s see how that works. I think thematically he works a little bit better than Ghidorah would have."4

Describing the genesis of the Gryphon for SciFi Japan, Rossio explained that, "To begin with, we wanted a flying monster. There`s something great about that image -- Godzilla standing his ground, an adversary attacking from above. The dynamics of the battle become more interesting. We also wanted to play into the conceit that our cultural myths recorded previous attacks and predicted future battles, so we searched for a creature supported by western mythology. And then the beauty of the Gryphon is that it seems constructed of several earth creatures, which led us to the notion of an alien Von Neumann type probe, that would construct a creature out of collected earth-type DNA."

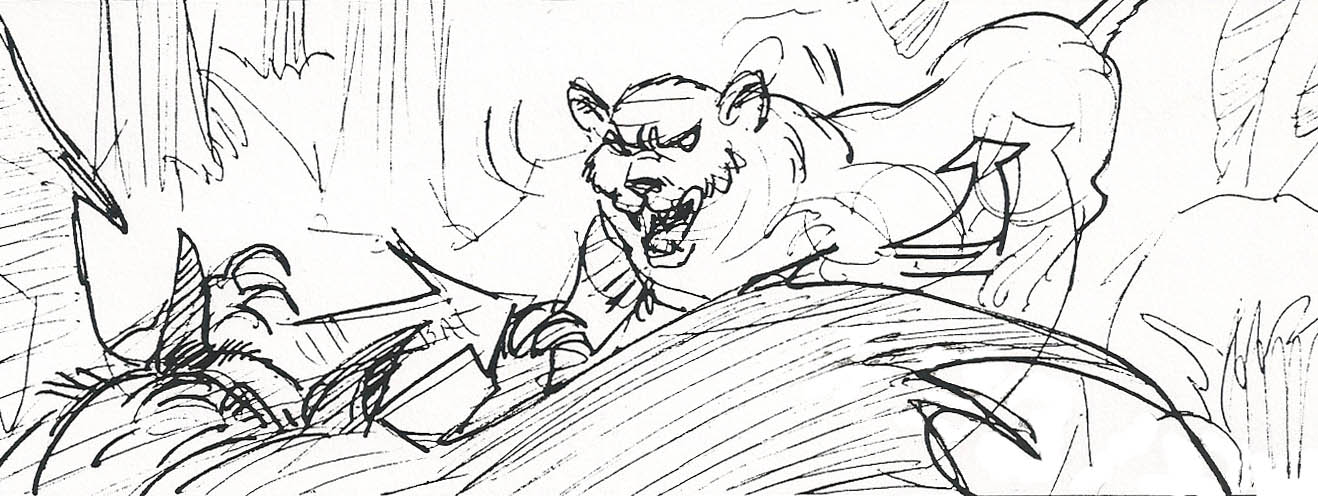

Unlike Ricardo Delgado, who had a mountain of Godzilla reference material at hand, Carlos Huante had nothing but the descriptions provided by the screenplay when it came to designing the Gryphon and the Probe Bats. The artist was also not given any specific instructions from either Jan De Bont or Joseph Nemec in regards to the look of the monsters.

"It was all up to me," Carlos explained. The script for GODZILLA describes the Gryphon as a planet-conquering "doomsday beast" that has "leathery, blood-red wings like a bat", "the body of a mountain lion", "smooth and slick skin", "eyes [that] glow yellow in the darkness, reflecting light like a cat`s eyes" and "many snakes, a hydra-headed thing, squirming where the tongue should be.” All of that presented a test for Huante. “To be honest, the description for the Gryphon was cartoony, so for me the challenge was to try and make it all real," he said.

Carlos Huante pencil rough and finished color illustration of the Gryphon. Images courtesy of the artist. © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.

Carlos Huante pencil rough and finished color illustration of the Gryphon. Images courtesy of the artist. © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.Despite the utter lack of reference material, Huante used a design process similar to Ricardo Delgado`s take on Godzilla by focusing on basic shapes that would catch the eye and create a strong impression on the viewer. "My approach was to find unique silhouettes that encase beautiful forms,” Huante recounted. He also drew inspiration from nature. “I remember that I stared at pictures of animals. Like I said, I just wanted the thing to look real, which wasn`t easy given the description. I also wanted the Gryphon to be able to stand upright on its hind legs and not look too awkward, being that it was meant to be a quadruped."

After coming up with a basic concept for the Gryphon, Huante created a number of illustrations depicting the monster with slightly different looks and in various poses. The Gryphon gradually evolved to resemble the classic interpretation of a biblical demon with horns, the wings and snout of a bat, and a humanoid torso. But the artist was never completely satisfied with the design of the creature, insisting that, "The Gryphon was what it was... I mean, there wasn`t really enough time to do many variations. The project got canned before I could reach the point that I wanted.“

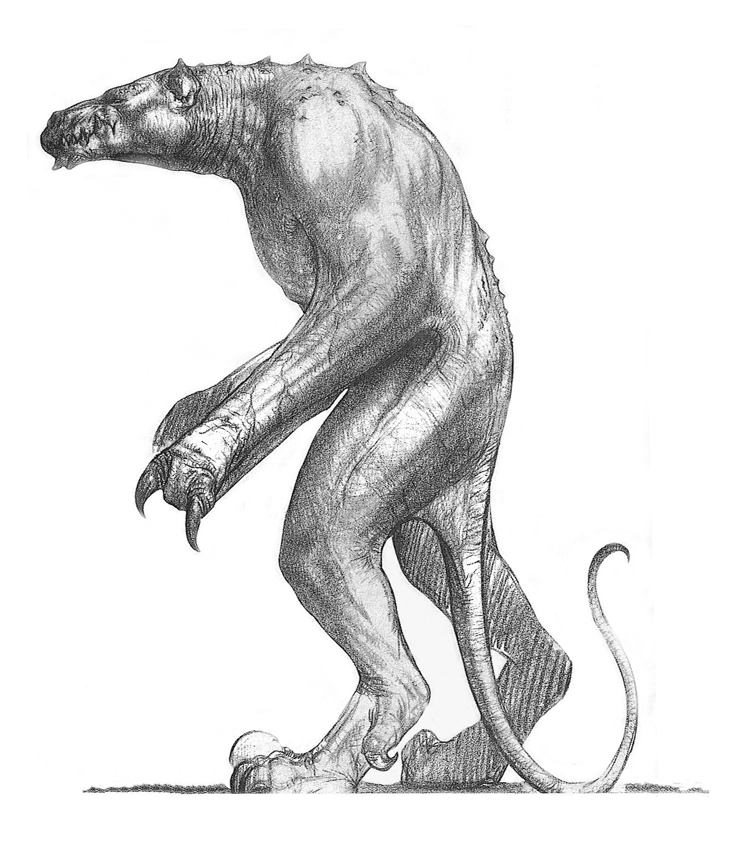

Carlos was happier with his work on the Probe Bats. The screenplay describes the creatures as bats that have been mutated by the alien probe, standing "roughly five feet tall" with "twelve-foot wingspans" and "bat-like features". From that, he was able to draw up a few different concepts and developed two key designs; one that closely matched the description in the script, and another he described as the `Turkey Vulture` which incorporated features of the large scavenger bird.

"The Turkey Vulture version of the Probe Bat was the one I liked best," he disclosed. "Jan liked that one also, so we were on the same page. I loved the way the neck of a vulture is cocked back so I tried to incorporate that into the design."

Two concept designs for the Probe Bats by Carlos Huante, including the “Turkey Vulture” version (right) favored by both the artist and director Jan De Bont. Images courtesy of Carlos Huante. © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.

Two concept designs for the Probe Bats by Carlos Huante, including the “Turkey Vulture” version (right) favored by both the artist and director Jan De Bont. Images courtesy of Carlos Huante. © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.Asked how many many concept illustrations he drew for GODZILLA, Huante replied, "I don`t even have an answer for this... a lot."

While their work pleased Jan DeBont and Joe Nemec, the artists never received any direct feedback from Toho and stayed out of any discussions between the Japanese studio and TriStar. "The studio dealt with Toho," recalled Ricardo Delgado.

"Toho was a little bit resistant at first," Jan De Bont acknowledged. "They didn’t want to change anything about Godzilla`s design. That was the whole point... I totally understood that. If it was something you’d worked on all your life and then somebody came in and changed the whole thing and turned it upside down it would be an issue. And the character was so liked by the Japanese people that you don’t want to change him too much." But the director was confident that he and his team were staying true to Godzilla, and Toho eventually gave their approval. "When they understood my enthusiasm for the character and how much I liked him they slowly changed."

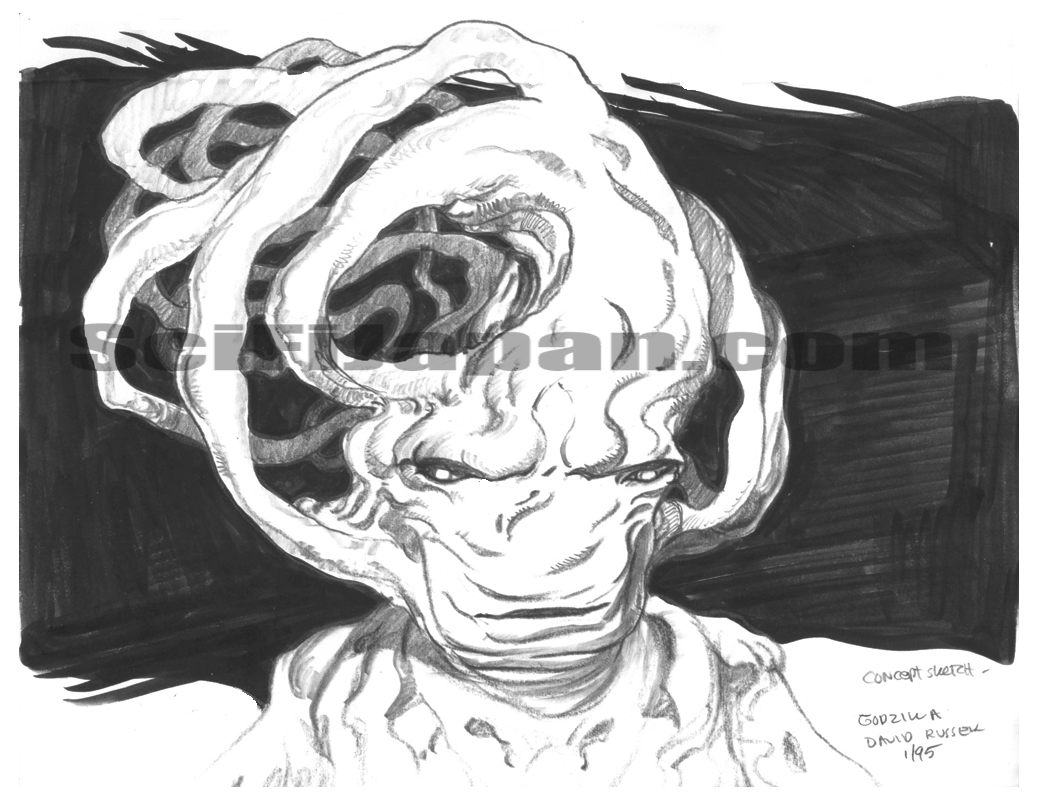

A third artist at Gojira Productions worked on yet another creature for GODZILLA. In the film`s story, the character Marty Kenoshita is infected by an alien organism that transforms his body into a constantly evolving, half-human/half-alien hybrid. During late 1994 and early 1995, some early designs for the "Marty/Alien" were drawn up by David Bryan Russell, a highly regarded artist who had previously worked on STAR WARS: RETURN OF THE JEDI (1983), WHO FRAMED ROGER RABBIT? (1988), BATMAN (1989), and TERMINATOR 2: JUDGMENT DAY.

"The Godzilla project was indeed interesting. The producers contacted me at the behest of Jan De Bont," Russell revealed to SciFi Japan. De Bont remembered that he had asked for David Russell because, "I had seen his drawings and they were so beautiful."

Alien design by David Russell. Image courtesy of David Russell. © 1994-1995 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.

Alien design by David Russell. Image courtesy of David Russell. © 1994-1995 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.Russell worked on GODZILLA for approximately five months, doing storyboards and character designs. "As a kid, I thoroughly enjoyed the Godzilla films," he said. "I likewise considered De Bont an interesting filmmaker, and I`d worked with Joe Nemec on two previous shows, THE COLOR PURPLE and TERMINATOR 2. Illustrators and storyboard artists are primarily aligned with the director and production designer, who are really in charge of the show`s visual development. Of course, most of this work is done at an early stage of a film`s evolution. This work [the alien concept sketches] was requested by the director."

Alien design by David Russell. Image courtesy of the artist. © 1994-1995 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.

Alien design by David Russell. Image courtesy of the artist. © 1994-1995 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.Like Carlos Huante with the Gryphon, he was not given any instructions regarding the physical appearance of the character, and was free to come up with his own designs. "As always, I was trying to create a different look for the aliens."

Russell`s alien designs are reminiscent of the work of Jack Kirby, the legendary comic book artist who co-created Captain America, the Fantastic Four, the Hulk, the Avengers, the X-Men, Thor, and a slew of other iconic characters for both Marvel and DC. Asked if the Kirby influence was intentional, David Russell answered, "Very much so. It was my discovery of Kirby`s work as a teen that set me on the path to becoming an artist. I later met Jack, and we became good friends. He remained a mentor until his passing. Jack was one of the best artists America has produced, and his work has deeply influenced the look and narrative power of contemporary films."

"These guys are really artists," De Bont said of the crew he and Joe Nemec had assembled. "It always amazes me that there are so many great storyboard and conceptual design artists that are absolutely fantastic. It’s like I said before... their work deserves to be in museums because it’s really quite unbelievable. The emotion that they can put into these big drawings that are so detailed, it just adds a layer of reality. I just have an incredible amount of respect for them."

In October 1994, Ricardo Delgado and Carlos Huante learned that Stan Winston`s lobbying had paid off; Winston Studio had been hired to do the monster designs. Delgado was greatly disappointed, but objective about the change: "Stan had a contractual agreement to design Godzilla, and it wasn’t until he was officially on the show that they told us, `Hey, we’re going with Stan`. And you know, I’m just a kid and Stan’s won multiple Oscars and he’s got a huge crew. Carlos and I were told that our services were being shifted over. After that, I believe we did some production drawings not related to the creatures."

Ice cavern concept art by Ricardo Delgado. Image courtesy of Jan De Bont. © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.

Ice cavern concept art by Ricardo Delgado. Image courtesy of Jan De Bont. © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.For a brief time it looked like Carlos Huante would stay on the project, but such thoughts were soon derailed by office politics. "Jan wanted me to follow through with Stan`s shop but, from what I understand, there were a couple of guys there that didn`t want me. An outsider coming in and art directing them? Oh, no..." Huante recounted. "I don`t know what happened between Jan wanting me on it, and these two guys there ignoring that fact and Stan -- of course -- supporting them, but I didn`t wait around for them to figure it out."

Unfinished Gryphon maquette sculpted by Carlos Huante. Photo courtesy of Jan De Bont. © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.

Unfinished Gryphon maquette sculpted by Carlos Huante. Photo courtesy of Jan De Bont. © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd."I was excited to see what Carlos did," Delgado said. "We saw our pencil and color sketches evolve into profile drawings and three dimensional sculpts. I started a Godzilla maquette and Carlos helped me with all his sculpting skills. He gave me advice on how to sculpt my creature. I was thrilled to see his sculpture, and I was always astonished at Carlos’ ability to meld classic sculpting with ingenious new production design."

"I got about halfway done with the Godzilla maquette before Carlos and I were told that Winston had gotten the bid and was going to execute the creature. And from that point, the sculpture just sat there for the rest of the time that I did production illustration on the show. And after that, it was either locked up in a warehouse like at the end of RAIDERS OF THE LOST ARK... or a bunch of grips got together and shot BBs at it one night. Who knows?”

"I don`t know what happened to the artwork I created after I left the project," Carlos Huante acknowledged. "I had started sculpting a maquette for the Gryphon but never got to finish it. I don`t have any photos for that one as I didn`t really finish it and it wasn`t anything that I thought mattered to me where it was left."

Delgado detailed his final stages on the project. "My timetable for GODZILLA is that I worked on it mid-to-late summer, and by October/November we were off the show," he recalled. "Carlos left before I did... he may have gone to work for Rob Bottin [the special effects artist known for THE HOWLING and John Carpenter`s THE THING], I’m not quite sure of that. I stayed on for a few weeks or months and did a few other production drawings. Some of them were pretty big. I did one drawing of the Gryphon`s den, where it undergoes its metamorphosis. I did a nice watercolor painting of the Arctic set and a few sketches of the ice cave where Godzilla awakens. To this day, I look at glacier stuff... they way that soil can fall into glaciers and dirty them up, create texture to them... I remember all that reference. And then the show got shelved completely at that point. I was there for that."

Gryphon`s den concept art by Ricardo Delgado. Image courtesy of Jan De Bont. © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.

Gryphon`s den concept art by Ricardo Delgado. Image courtesy of Jan De Bont. © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.Despite the disappointment of how things ended, Carlos Huante looks back at his time working on GODZILLA with Ricardo Delgado as a positive experience. "As I said earlier we were a tight knit group; Ricardo and I are friends to this day." The two artists would work together again on MEN IN BLACK.

Godzilla profile by Ricardo Delgado, done as a guide for his maquette of the monster. © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/Toho Co., Ltd.

Godzilla profile by Ricardo Delgado, done as a guide for his maquette of the monster. © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/Toho Co., Ltd."It was a pleasure, not just as an artist, but as a friend to work with him," agreed Delgado. "All we would talk about was the classic Toho movies. Carlos is a really big fan of WAR OF THE GARGANTUAS and I love that film too, and we would always just laugh about how cool it was to be working on GODZILLA. At one point it looked like both of our characters would go all the way through [the production process] and be realized onscreen. It was such a fantastic thing for both of us to sit there and think that we could watch each other’s creatures slug it out. That’s something that young artists dream about, and for a while there we were both living that dream. My only regret is that, from a friendship perspective, that didn’t happen. I don`t think if we could have watched Winston’s creatures do battle that would have been as much fun."

"While I was bummed that the film didn’t get made it was a pleasure to work on it," he reflected. "And even today, I look at my Godzilla design and I’ve seen some of the other stuff that’s been done... and after all I’ve done since, I still feel proud of my design."

Unfinished Godzilla maquette by Ricardo Delgado, displayed with a partial model of the hangar where the monster is held (see the

Unfinished Godzilla maquette by Ricardo Delgado, displayed with a partial model of the hangar where the monster is held (see the  Header for David Russell`s storyboard pages. Image courtesy of David Russell. © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.

Header for David Russell`s storyboard pages. Image courtesy of David Russell. © 1994 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd.STORYBOARDS

"I was on GODZILLA for about three months, before Sony pulled the plug." --storyboard artist Giacomo Ghiazza

The storyboards for GODZILLA were drawn by David Russell and another talented artist, Giacomo Ghiazza, during the final months of 1994. Like Russell, Ghiazza has been working steadily as a storyboard artist and illustrator for decades; his long list of credits began with TOTAL RECALL (1990) and ROBOCOP 2 (1990).

"I had previously worked with Jan De Bont on SPEED, so he called me again," Ghiazza recalled for SciFi Japan. "I was on GODZILLA for about three months, before Sony pulled the plug."

"Giacomo is nice and quick," praised Jan De Bont. "I also worked with him a lot on commercials. He knows me and knows the different kinds of angles that I like to have with multiple cameras and how that can be effective." After collaborating once again with De Bont on TWISTER, Ghiazza would do storyboards for STARSHIP TROOPERS (1997), MIGHTY JOE YOUNG, HOLLOW MAN (2000), WINDTALKERS (2002), PAYCHECK (2003), PIRATES OF THE CARIBBEAN: THE CURSE OF THE BLACK PEARL, LEMONY SNICKET`S A SERIES OF UNFORTUNATE EVENTS (2004), MISSION: IMPOSSIBLE III (2006), KNIGHT AND DAY (2010) and AUGUST: OSAGE COUNTY (2013). "[In 2010] I worked on PIRATES OF THE CARIBBEAN: ON STRANGER TIDES then on LIFE OF PI with Ang Lee, which I consider the best working experience that I can remember."

Thinking back, Giacomo Ghiazza remembered that, "David Russell and I were the only two storyboard artists on GODZILLA. I don`t recall how many scenes I boarded, but I would guess several, being such an action-packed film."

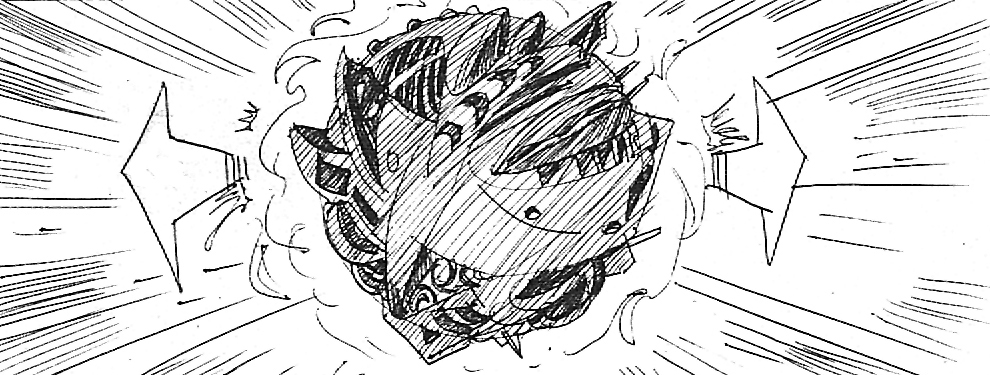

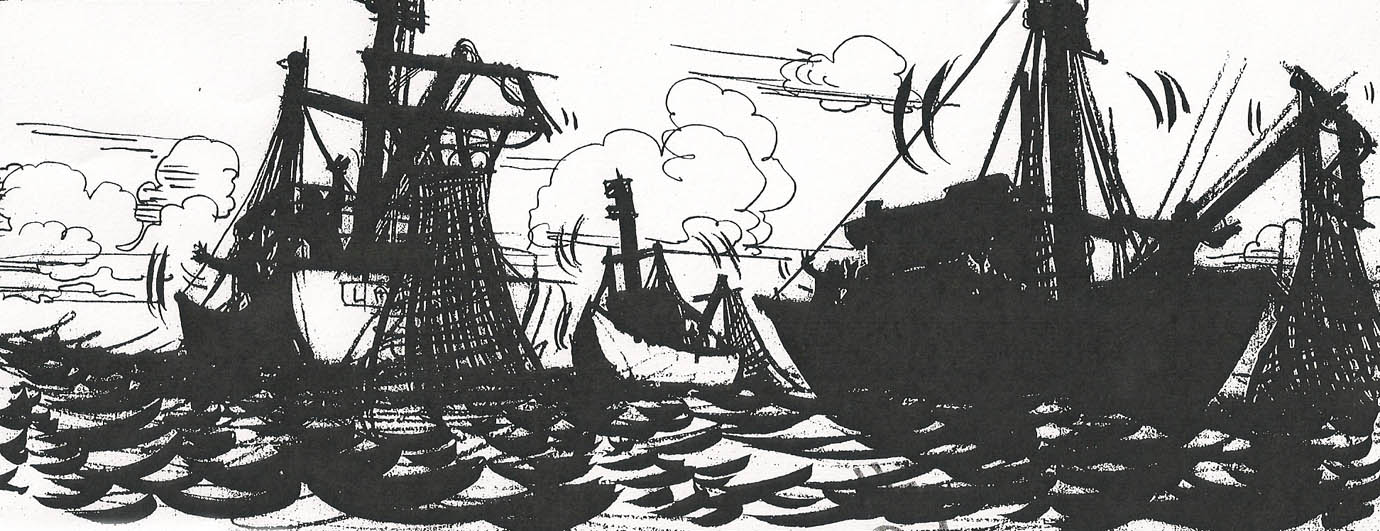

David Russell stated, "I drew four scenes in total, each rather challenging, though please note that I did not work on any sequences featuring Godzilla himself." While Godzilla did not appear in Russell`s boards, the artist did draw major scenes for the Gryphon and the Probe Bats. "The two remaining sequences are the sinking of the fishing boats and the probe`s earth impact, resulting in a rain of fish, frogs, etc. The latter scene is a rough board."

The look of the creatures in the storyboards were based on Carlos Huante and Ricardo Delgado`s creature designs. "Along with Jan and Joe Nemec, they were the ones who gave the look to the movie. I used some of Ricardo`s drawings for reference," Ghiazza explained. Russell added that, "Ricardo and Carlos created very beautiful concept art. Ricardo -- an expert on dinosaur design -- had a tremendous influence over the evolving look of the characters."

No concept designs were created for the alien probe. "I worked from Jan`s verbal description of the probe," Russell revealed. "

He really understood what I was trying to do with those different angles, camera movements and motions, and he was able to get that in those storyboards," De Bont explained. "In addition, he made every drawing like a little art piece; they were some spectacular drawings. You don’t expect that so much for a storyboard... generally, they’re more simple but he had to make it look real. He couldn’t not do that."

Ricardo Delgado also had a lot of praise for his fellow artists. "The storyboards were all Giacomo and David," he remarked. "They were on a different floor [of Gojira Productions] than Carlos and I were... they were on a floor above us, closer to Jan’s office. I would often go up there and talk with them and see what they were doing, and it was really cool to see the artwork of the creatures slamming into skyscrapers. It was pretty amazing. I thought the sequence where they render Godzilla unconscious on the Golden Gate Bridge was fantastic. He wipes out the Pacific Fleet in the process, and yet wakes from his slumber to fight for humanity and kick the Gryphon`s butt. I think that would have been a lot of fun for everyone to see."

Jan De Bont was very involved in the storyboarding process, working closely with the artists. "I was dealing directly with Jan for the boards," Giacomo Ghiazza recalled. David Russell concurred, adding that the director`s background as a cinematographer had a direct impact on the look of the storyboards: "I worked at Jan`s instructions. He was very specific about his shots, often providing extensive shot lists for the storyboard team, which is unusual."

De Bont was very pleased with the collaboration, saying, "They were a good team, the two of them. They had different styles; Russell for when the pictures had to be really detailed, and Giacomo for when the action was very important. They deserve all the attention they get because they’re really good."

The following storyboard sequences are courtesy of David Russell, Giacomo Ghiazza, Terry Rossio and Jan De Bont. They are presented in sequential order, with chapter titles taken from TriStar`s GODZILLA production documents. Click on each storyboard image below to see a complete set of storyboards for that scene...

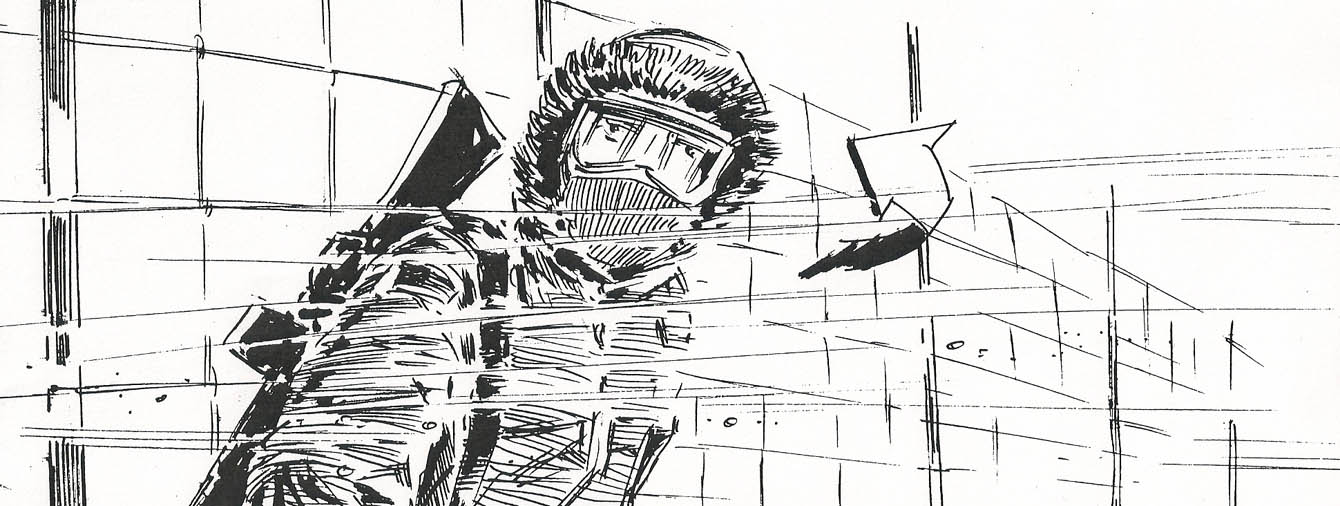

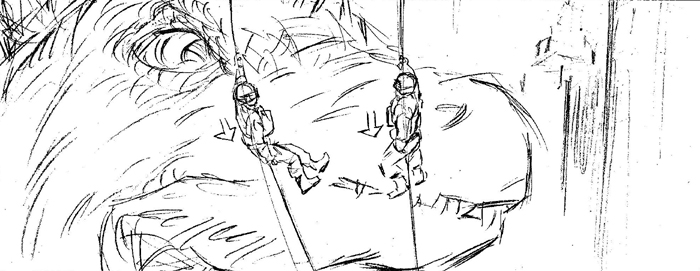

• Arctic Ocean: Giacomo Ghiazza The opening sequence of GODZILLA reveals the film`s onscreen title and shows the salvage ship disaster that leads to the monster`s awakening...

• Llewellyn Home: Giacomo Ghiazza Government scientists Keith and Jill Llewellyn share a romantic moment before being called away on a top secret assignment. This sequence also introduces their daughter, Tina.

• Kuril Island: Giacomo Ghiazza Godzilla makes his first public appearance, destroying a fishing village on an island off the coast of Japan.

• Traveller, UT (rough): David Russell The sudden arrival of an alien probe has an immediate impact on the residents of a small Utah town...

• Bat Attack: David Russell The alien probe begins to absorb local lifeforms for a sinister purpose...

• Cougar Kill: David Russell A mountain lion is attacked by bats mutated by the alien probe...

• Arctic Outpost: Giacomo Ghiazza Something strange happens at the site where Godzilla was first discovered...

• Larry, Moe & Curly: David Russell Three unlucky fishing boats have a run-in at sea with Godzilla. Note: Only low resolution scans were available for this sequence.

• Armada Fight: Giacomo Ghiazza The US military confronts Godzilla in the waters off San Francisco.

• Submarine: Giacomo Ghiazza Godzilla makes short work of a submarine and a destroyer.

• Fluid/Bridge: Giacomo Ghiazza Godzilla unknowingly falls into a trap before climbing the Golden Gate Bridge.

• Church Attack: David Russell A congregation falls victim to man-sized Probe Bats.

• Bat Cave: David Russell The Probe Bats bring their prey back to the Gryphon`s lair...

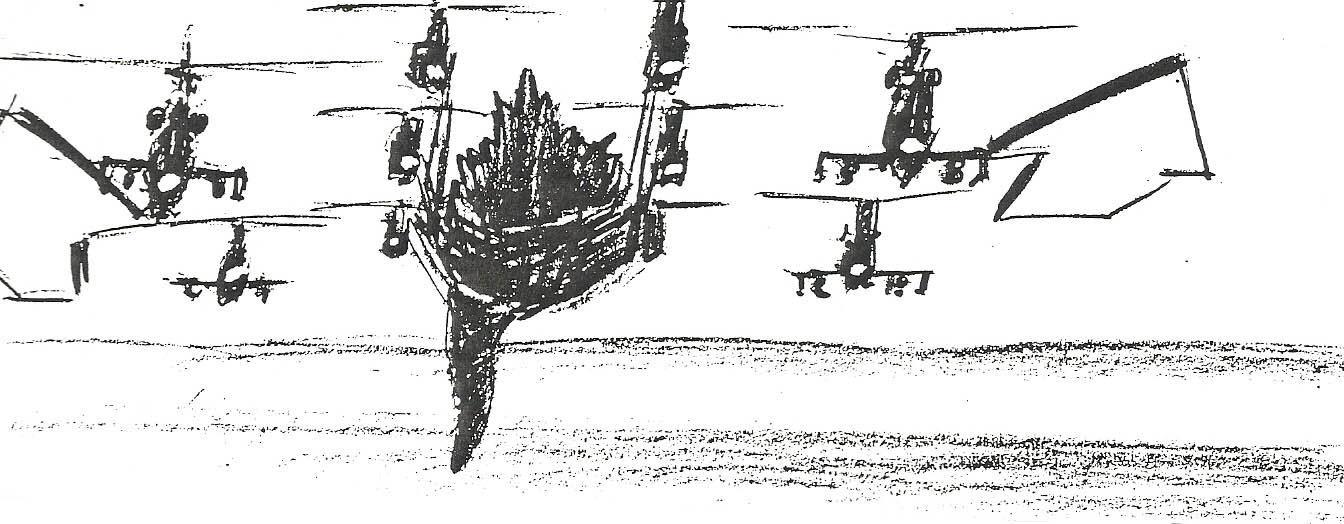

• Transport: Giacomo Ghiazza Two boys watch as the unconscious Godzilla is airlifted to a secure location.

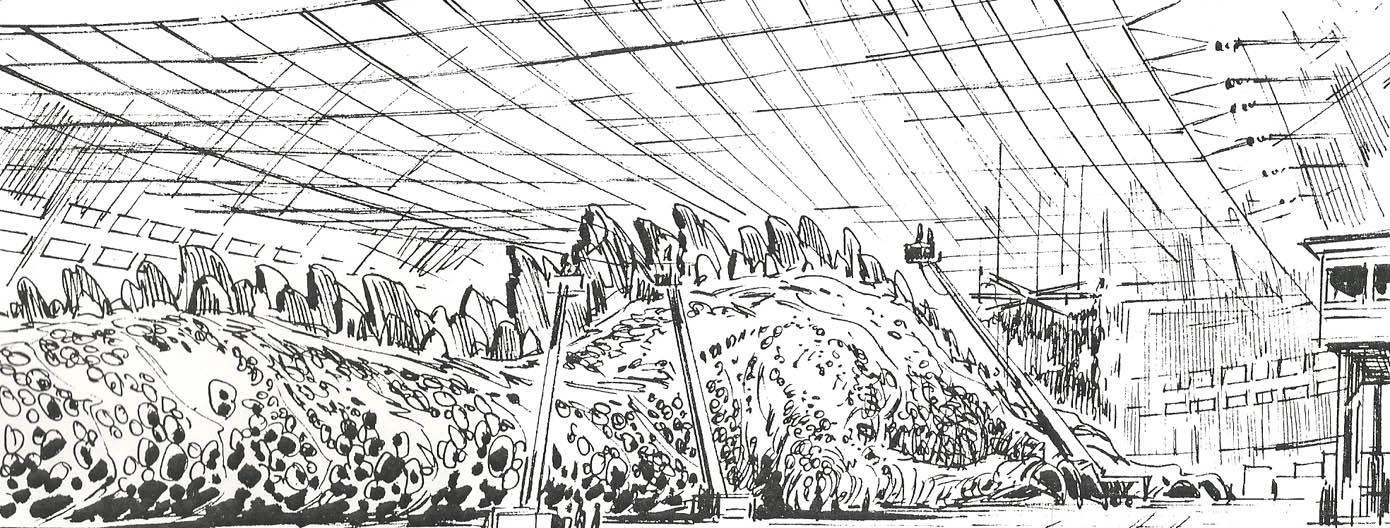

• Holding Tank: Giacomo Ghiazza Jill Llewellyn arrives at the facility where Godzilla is kept under sedation.

• Hangar: Giacomo Ghiazza Jill and her daughter Tina disagree on whether or not Godzilla should be killed.

• The Gryphon Rises: David Russell Having completed its gestation, the Gryphon emerges to conquer the world.

• Godzilla`s Escape: Giacomo Ghiazza Sensing the Gryphon, Godzilla awakens and attempts to break free of his confinement.

• Final Battle: Part I: Giacomo Ghiazza Jill races to rescue her daughter as the Gryphon and Godzilla arrive in New York City. Note: This sequence includes handwritten notes by Jan De Bont.

• Final Battle: Part II: Giacomo Ghiazza The monsters clash between the towers of the World Trade Center.

• Final Battle: Part III: Giacomo Ghiazza Aaron Vaught and Nelson Fleer come to Godzilla`s aid while Pike engages the Gryphon in aerial combat around the Empire State Building.

© 1993-1995 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd. © Stan Winston Studio © 1994 Sony Pictures Imageworks

© 1993-1995 Sony Pictures Entertainment/ Toho Co., Ltd. © Stan Winston Studio © 1994 Sony Pictures ImageworksNOTES

JAN De BONT

1. Donna Parker, Monstrous Deal for De Bont: New GODZILLA, The Hollywood Reporter Vol. 232 #42, June 28, 1994, p57?

2. Chris Nashawaty, Stomp the World, I Want to Get Off, Entertainment Weekly #433, May 22, 1998, p27?

3. Rex Weiner, De Bont Helms New GODZILLA, Daily Variety, July 8, 1994, p3?

4. Mark Salisbury, Monster Invasion: Godzilla, Fangoria #140, March 1995, p10?

5. Donna Parker, Monstrous Deal for De Bont: New GODZILLA, The Hollywood Reporter Vol. 232 #42, June 28, 1994, p57?

6. Mark Salisbury, Monster Invasion: Godzilla, Fangoria #140, March 1995, p10?

7. Rex Weiner, De Bont Helms New GODZILLA, Daily Variety, July 8, 1994, p3?

8. Rex Weiner, De Bont Helms New GODZILLA, Daily Variety, July 8, 1994, p19?

9. Donna Parker, Monstrous Deal for De Bont: New GODZILLA, The Hollywood Reporter Vol. 232 #42, June 28, 1994, p57?

10. Rex Weiner, De Bont Helms New GODZILLA, Daily Variety, July 8, 1994, p19?

11. Steve Ryfle, I`m Ready For My Close-Up, Mr. De Bont, Sci-Fi Universe #5, February/March 1995, p51?

12. Chris Nashawaty, Stomp the World, I Want to Get Off, Entertainment Weekly #433, May 22, 1998, p27?

13. Tom Shone, Blockbuster: How Hollywood Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Summer, (Free Press, 2004), p269?

14. Rachel Aberly, The Making of GODZILLA, (HarperPrism, 1998), p17?

15. Mark Salisbury, Monster Invasion: Godzilla, Fangoria #140, March 1995, p10?

16. Teresa Watanabe, Godzilla Suits Up Again: Low-Tech Dinosaur Is Due for High-Tech Hollywood Make-Over, Los Angeles Times, August 1, 1994?

17. Jim Bailey, Your City Could Be Next: Now, Godzilla Takes on the World, Asiaweek, December 21-28, 1994, pp38-43?

PRE-PRODUCTION BEGINS

1. Mark Salisbury, Monster Invasion: Godzilla, Fangoria #140, March 1995, p10?

CONCEPTUAL DESIGN, ROUND ONE: GOJIRA PRODUCTIONS and STAN WINSTON

1. Stephen Rebello, Stan Winston: The Michelangelo of Monsters, Movieline, November 1, 1994?

2. Don Shay and Jody Duncan, The Making of JURASSIC PARK, (Ballantine Books, 1993), p22?

3. Steve Ryfle, Japan`s Favorite Mon-Star, (ECW Press, 1999), p331?

4. Ibid.?